(TL;DR) Eric Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics remains one of the clearest guides to our modern disorder. It teaches that when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void—and history descends into Gnostic fantasy. Voegelin’s remedy is not new revolution but ancient remembrance: the recovery of the soul’s openness to reality.

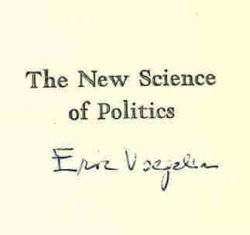

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) was an Austrian-American political philosopher who sought to diagnose the spiritual derangements of modernity. In his 1952 classic The New Science of Politics—first delivered as the Walgreen Lectures at the University of Chicago—Voegelin proposed that politics cannot be understood as a merely empirical or procedural science. Power, institutions, and law arise from a deeper spiritual ground: humanity’s participation in transcendent order. When societies lose awareness of that participation, they fall into ideological dreams that promise salvation through human effort alone. The book is therefore both a critique of modernity and a call to recover the classical and Christian understanding of political reality (Voegelin 1952, 1–26).

1. The Loss of Representational Truth

Every stable society, Voegelin argued, “represents” its members within a larger order of being. In ancient civilizations and medieval Christendom, political authority symbolized this participation through myth, ritual, and law that acknowledged a reality beyond human control. The ruler was not a god but a mediator between the temporal and the eternal.

Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the monk Joachim of Fiore reimagined history as a self-unfolding divine drama in which humanity itself would bring about the final age of perfection. With this shift, Western consciousness began to “immanentize the eschaton”—to relocate ultimate meaning inside history rather than in its transcendent source. Out of this inversion grew the modern ideologies of progress (Comte, Hegel), revolution (Marx), and race (National Socialism), each promising earthly redemption through planning and will (Voegelin 1952, 107–132).

For Voegelin, the loss of representational truth meant that governments no longer reflected humanity’s place in divine order but instead projected utopian images of what they wished reality to be. Politics ceased to be the articulation of truth and became the engineering of salvation.

2. Gnosticism as the Modern Disease

Voegelin identified the inner structure of these movements as Gnostic. Ancient Gnostics sought hidden knowledge that would liberate the soul from an evil world; their modern successors, he said, sought knowledge that would liberate humanity from history itself. “The essence of modernity,” Voegelin wrote, “is the growth of Gnostic speculation” (1952, 166).

He listed six recurrent traits of the Gnostic attitude:

- Dissatisfaction with the world as it is.

- Conviction that its evils are remediable.

- Belief in salvation through human action.

- Assumption that history follows a knowable course.

- Faith in a vanguard who possess the saving knowledge.

- Readiness to use coercion to realize the dream.

From medieval millenarian sects to twentieth-century totalitarian states, these traits form a single continuum of spiritual rebellion: the attempt to perfect existence by abolishing its limits.

3. The Open Soul and the Pathologies of Closure

Against the Gnostic impulse stands the open soul—the philosophical disposition that accepts the “metaxy,” or the in-between nature of human existence. We live neither wholly in transcendence nor wholly in immanence, but within the tension between them. The philosopher’s task is not to resolve that tension through fantasy or reduction but to dwell within it in faith and reason.

Political science, therefore, must be noetic—concerned with insight into the structure of reality—not merely empirical. A society’s symbols, institutions, and laws can be judged by how faithfully they articulate humanity’s participation in divine order. Disorder, Voegelin warned, begins not with bad policy but with pneumopathology—a sickness of the spirit that refuses reality’s truth. “The order of history,” he wrote, “emerges from the history of order in the soul.”

Empirical data can measure economic growth or electoral results, but it cannot measure spiritual health. That requires awareness of being itself.

4. Liberalism’s Vulnerability and the Way of Recovery

Voegelin saw liberal democracies as historically successful yet spiritually precarious. By reducing political order to procedural legitimacy and rights management, liberalism risks drifting into the nihilism it opposes. When public life forgets its transcendent foundation, freedom degenerates into relativism, and pluralism becomes mere fragmentation.

Still, Voegelin’s outlook was not despairing. His proposed remedy was anamnesis—the recollective recovery of forgotten truth. This is not nostalgia but awakening: the rediscovery that human beings are participants in an order they did not create and cannot abolish. The recovery of the classic (Platonic-Aristotelian) and Christian understanding of existence offers the only durable antidote to ideological apocalypse (Voegelin 1952, 165–190).

To “keep open the soul,” as Voegelin put it, is to resist every movement that promises paradise through force or theory. The alternative is the descent into spiritual closure—an ever-recurring temptation of modernity.

5. Contemporary Resonance

Voegelin’s analysis remains uncannily prescient. Today’s ideological battles—whether framed around identity, technology, or climate—often echo the same Gnostic pattern: discontent with the world as it is, belief that perfection lies just one policy or re-education campaign away, and impatience with reality’s resistance. The post-modern conviction that truth is socially constructed continues the old dream of remaking existence through will and language.

Voegelin’s warning cuts through our century as clearly as it did the last: when politics replaces truth with narrative and transcendence with activism, society repeats the ancient heresy in secular form. The cure, as ever, is humility before what is—the recognition that order is discovered, not invented.

References

Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Glenn. 2003. Transcendence and History: The Search for Ultimacy from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Sandoz, Ellis. 1981. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glossary of Key Terms

Anamnesis – Recollective recovery of forgotten truth about being.

Gnosticism – Revolt against the tension of existence through claims to saving knowledge that masters reality.

Immanentize the eschaton – To locate final meaning and salvation within history rather than beyond it.

Metaxy – The “in-between” condition of human existence, suspended between immanence and transcendence.

Noetic – Pertaining to intellectual or spiritual insight into reality’s order.

Pneumopathology – Spiritual sickness of the soul that closes itself to transcendent reality.

Representation – The symbolic and political articulation of a society’s participation in transcendent order.

4 comments

Comments feed for this article

November 10, 2025 at 7:08 am

Steve Ruis

Re “… when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void …” right … And, who provides access to the reservoir of transcendent truth? Hmmm? More hogwash on top of old hogwash trying to make the old hogwash still pertinent.

LikeLike

November 10, 2025 at 8:15 am

The Arbourist

Morning Steve,

Your scoff at “hogwash” misses Voegelin’s point: transcendent truth is no clerical reservoir but the participatory order of reality, encountered through noetic insight and anamnesis in the metaxy—the tense in-between of immanence and transcendence. The crisis lies in epistemic humility’s absence, without which politics devolves into Gnostic fantasies of mastery over history, be they theistic, atheistic, or technocratic. Order is discovered in open recognition of limits, not engineered through closed ideological certainty.

Didn’t mean to set off your atheism, but whats going on is that Voegelin is proposing that, to maintain a free liberal society, we must avoid dogmatic belief in any form and face our reality with a sound epistemological basis.

LikeLike

November 10, 2025 at 8:18 am

Steve Ruis

You lost me at “the participatory order of reality” and the other “locations”, such as “the tense in-between of immanence and transcendence” again refer to imaginary realms only apparent to acolytes of mysticism.

LikeLike

November 10, 2025 at 8:23 am

The Arbourist

@Steve

Those phrases are not mystical portals but precise descriptions of human existence as finite yet oriented toward meaning beyond mere survival—something Plato called the soul’s eros for the good, Aristotle the contemplative life, and even secular thinkers like Arendt the “space of appearance” where freedom emerges. Voegelin’s point is brutally practical: when politics forgets that we do not create the ground of order but participate in it, it slides into the hubris of total planning—whether Marxist, Nazi, or today’s algorithmic utopias. Epistemic humility means admitting we know in part, act under uncertainty, and resist the Gnostic temptation to “fix” reality by force. No acolytes required; just the courage to live without illusions of omniscience.

LikeLike