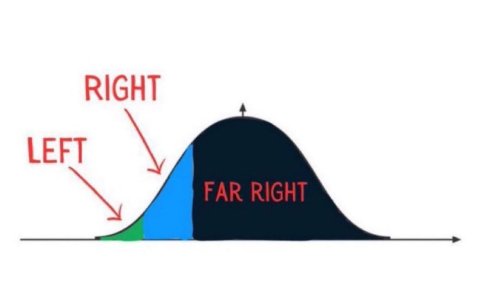

Online discourse is exhausting for a simple reason: certain words are used not to describe reality, but to end the conversation. The label does the work. The argument never has to.

“Fascist” is one of those words.

In current usage, it often functions as a moral airhorn: you’re beyond the pale; you’re dangerous; you’re not worth debating. It gets tossed at people over ordinary ideological disputes about sex and gender, about speech norms, about state power, about immigration, about education. Sometimes it’s malice. Sometimes it’s a sincere attempt to name something authoritarian using the most nuclear term available. Either way, the practical effect is the same: “fascist” becomes a conversation-stopper rather than a description.

That’s why definitions matter. Not because language never evolves (it does), but because political language has consequences. When a term carries a freight of historical evil, using it casually is not “rhetorical adaptation.” It’s moral inflation. Moral inflation does not stay rhetorical for long.

Fascism isn’t just “authoritarian”

Start with what fascism is not.

Fascism is not merely “oppressive, dictatorial control.” That’s too broad. Plenty of regimes are oppressive. Plenty of dictators are brutal. If “fascist” just means “authoritarian,” it becomes a synonym for “bad,” and then it means nothing at all.

Fascism is a historically specific modern political project. A workable definition, tight enough to guide usage and broad enough to cover the main cases, looks like this:

Fascism is an authoritarian mass movement aimed at national rebirth, organized around the leader principle, hostile to liberal constraints (pluralism, due process, free speech), willing to use intimidation or violence against opponents, and committed to subordinating institutions to a single national story.

Notice the “mass movement” piece. Fascism is not only what the state does; it’s what a mobilized public is trained to do for the regime. It does not merely punish dissent. It cultivates a moral atmosphere in which dissent feels like treason, contamination, sabotage.

Economically, fascist systems often preserve nominal private ownership while subordinating markets, labour, and industry to regime goals through state direction and corporatist control. That’s not the essence, but it’s part of the recognizable package: the economy exists for the national project, not the other way around.

History: what it looked like when it was real

Words should cash out in the world.

Historically, fascism is anchored in early 20th-century Europe, most centrally Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. They differed in important ways, but the family resemblance is clear: politics becomes a spiritual drama of national humiliation and promised restoration; the leader becomes the embodiment of the nation; opposition becomes illegitimate by definition; and coercion becomes normalized as “necessary” for unity and renewal.

The methods are recognizably modern: propaganda, spectacle, the disciplining of media and education, the weaponization of law, the tolerated use of street-level intimidation, and the steady narrowing of permissible speech and association. It’s not merely “the government is strong.” It’s the fusion of power with myth, enforced socially and legally.

A practical threshold: not one trait, a cluster

If you want to use “fascist” responsibly, you need a threshold. Not a single feature, a cluster.

The label starts to become warranted only when several of these are present together:

- Leader principle: politics organized around a singular figure or party claiming a unique right to rule.

- Myth of national rebirth: humiliation plus promised restoration demanding unity and purification.

- Anti-pluralism: opponents treated as enemies, not fellow citizens.

- Suppression of dissent: legal, institutional, or social narrowing of speech and association.

- Propaganda and spectacle: mass emotional mobilization replacing open contest.

- Normalization of intimidation: harassment, threats, “consequences,” or violence used as political tools.

- Institutional capture: courts, schools, media, and professions bent into ideological instruments.

This is also how you keep your head when the internet offers you cheap clarity. If someone is merely wrong, stubborn, rude, or convinced, that is not fascism. If someone wants stronger regulation, that is not fascism. If someone defends free speech, or argues about sex and gender, that is certainly not fascism by definition. Those are disputes inside ordinary politics, however heated.

A concrete misuse: the pattern in miniature

Here’s the move you see constantly:

A person says, “I think compelled speech policies in workplaces and schools are a mistake.”

The reply is not, “I disagree, because…”

The reply is, “Fascist.”

What did the label accomplish? It converted a claim about policy into an accusation about moral essence. It implied the speaker is not merely mistaken but dangerous; not merely wrong but disqualifying. Once you have categorized someone as a “fascist,” the next steps feel justified: deplatforming, professional punishment, social exile, denial of hearing.

Maybe the labeler was “just venting.” Maybe it was “good-faith hyperbole.” But hyperbole has downstream effects. It trains the audience to treat coercion as civic hygiene.

Symmetry: this is not a left-only sin

And yes: the right does its own version. “Marxist” becomes a synonym for “liberal.” “Communist” becomes “anyone who wants a program.” “Groomer” becomes a sloppy club for any disagreement about education. “Traitor” becomes shorthand for “opponent who won.” Same mechanism, different tribe: labels as argument-substitutes and permission structures.

If we’re going to complain about language used as a weapon, we don’t get to only notice it when it hits our side.

Why this matters beyond the internet

The problem isn’t just vibes on social media. Label inflation spills into institutions.

When terms like “fascist” become casual descriptors, workplaces and professional bodies begin treating contested political disagreement as a safety issue. Media narratives start pre-sorting dissent as extremism. Politicians learn to substitute moral denunciation for persuasion. The public learns to fear argument and love punishment.

The final irony is that this habit corrodes the liberal norms that make pluralistic society possible: the expectation of disagreement, the discipline of evidence, and the moral restraint of not treating opponents as vermin.

A better standard

Here’s the rule I’m adopting: I’ll reserve “fascist” for cases where I can point to the cluster. Leader principle, anti-pluralism, suppression, intimidation, institutional capture, mythic rebirth. Not merely the heat of the dispute.

When I mean “authoritarian,” I’ll say authoritarian. When I mean “illiberal,” I’ll say illiberal. When I mean “coercive,” I’ll say coercive.

Definitions aren’t pedantry. They are the line between argument and excommunication, a public safety measure for language. “Fascist” should be a diagnosis you can defend, not a mood you can perform. If we flatten every disagreement into fascism, we train ourselves to crave punishment instead of persuasion, and we teach institutions to treat dissent as contamination. That habit does not protect democracy. It rots the muscles that make democracy possible, and it turns politics into a brawl we will eventually call governance.

Your opinions…