Erik Erikson is still useful because he blocks a modern temptation: reading a child’s self-descriptions as evidence of a finished, stable identity. For Erikson, identity is not an inner essence that appears early and then merely announces itself. It is something built across time under social conditions. Relationships, cultural scripts, permissions, limits, and feedback all shape what a person can plausibly become and what they can sustain. If you want a single takeaway, it is this: adults regularly project mature coherence onto children whose sense of “who I am” is still under construction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

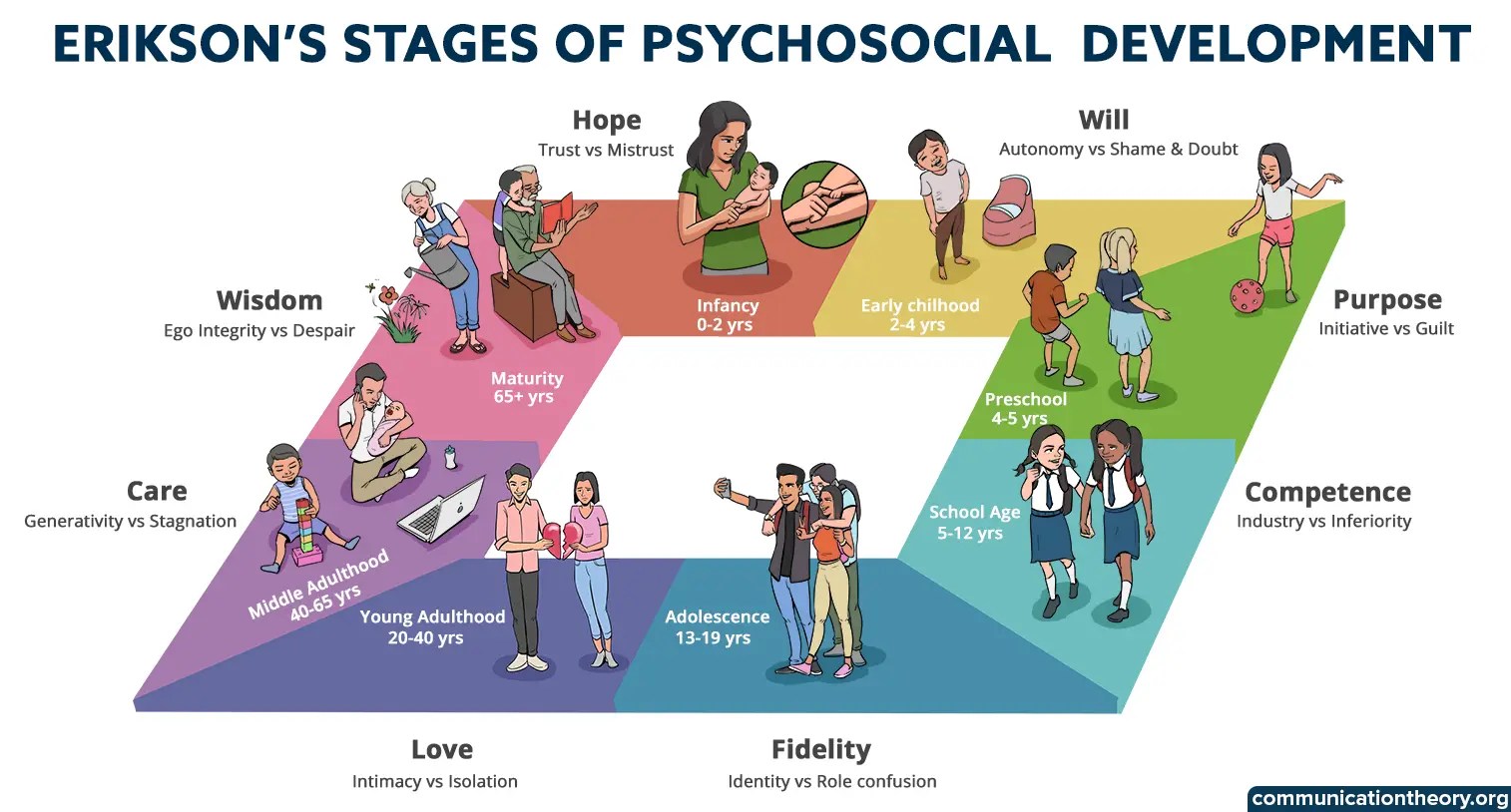

Erikson’s framework is psychosocial. He describes eight broad stages across the lifespan, each organized around a tension between two outcomes. The point is not a one-time pass or fail. It is a developmental task that tends to recur in new forms as life changes. When conditions are supportive, people lean toward the positive resolution and develop an associated strength or “virtue.” When conditions are hostile or mismatched, the negative pole can dominate and leave a durable vulnerability. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

In early childhood, the tasks are basic but not trivial. In infancy, trust versus mistrust is shaped by whether care is reliable and responsive. In toddlerhood, autonomy versus shame and doubt turns on whether a child can attempt self-control without being humiliated for mistakes. In the preschool years, initiative versus guilt turns on whether exploration and planning are welcomed or punished. These are not destiny. They are early patterns. They set default expectations about safety, agency, and permission that can be reinforced later or revised by later experience. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

School age brings industry versus inferiority. Children now meet the world of tasks, standards, and comparison. Competence grows when effort produces mastery and feedback is fair. Inferiority grows when failure is repeated, demands are mismatched, or judgment is harsh. This matters because it supplies the raw materials for adolescence. Identity versus role confusion is not about picking a label. It is about synthesizing roles, values, loyalties, and a changing body into something that feels continuous and workable. Researchers made this more testable by focusing on processes like exploration and commitment (roughly, trying roles out and then making durable choices), yielding familiar identity-status patterns such as diffusion, foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement. Longitudinal work also supports the commonsense point that identity development extends beyond the teen years for many people. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Erikson’s model deserves the criticisms it often receives. The stages function best as descriptive heuristics rather than strict schedules, and some concepts are hard to measure cleanly. The framework also reflects mid-20th-century Western assumptions, and feminist scholarship has pressed on its gendered blind spots. Still, the core insight survives: selfhood is social before it is philosophical. Children become “someone” through attachment, modeling, constraint, opportunity, and recognition. The practical reminder is blunt, feeding directly into today’s debates. Do not read adult-level identity stability into young children’s words or preferences. Much of what looks like certainty in a child is a snapshot of roles and reinforcement, not proof of a permanent inner core. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Glossary

- Psychosocial stage/task: A recurring developmental challenge shaped by social context, not a biological timer. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Virtue (Erikson): A strength associated with a relatively positive resolution of a stage task (e.g., hope, will, competence, fidelity). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity vs role confusion: The adolescent task of developing a workable sense of continuity across roles, values, and future direction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity statuses (Marcia tradition): A research approach using exploration and commitment to classify patterns like diffusion (low both), foreclosure (commitment without exploration), moratorium (exploration without commitment), and achievement (exploration leading to commitment). (Wikipedia)

Endnotes

- Erikson stages overview, virtues, and the “not pass/fail” framing: StatPearls (Orenstein, 2022). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Scholarly overview and modern framing of Erikson as a lifespan theory: Syed & McLean (2017, PsyArXiv).

- Identity-status trajectories and measurement of exploration/commitment over time: Meeus (2011, PMC). (Wikipedia)

- Marcia identity-status grounding in Eriksonian identity crisis: foundational identity-status paper (PDF record).

- Feminist critique and gender-bias discussion of Eriksonian identity: Sorell (2001).

Your opinions…