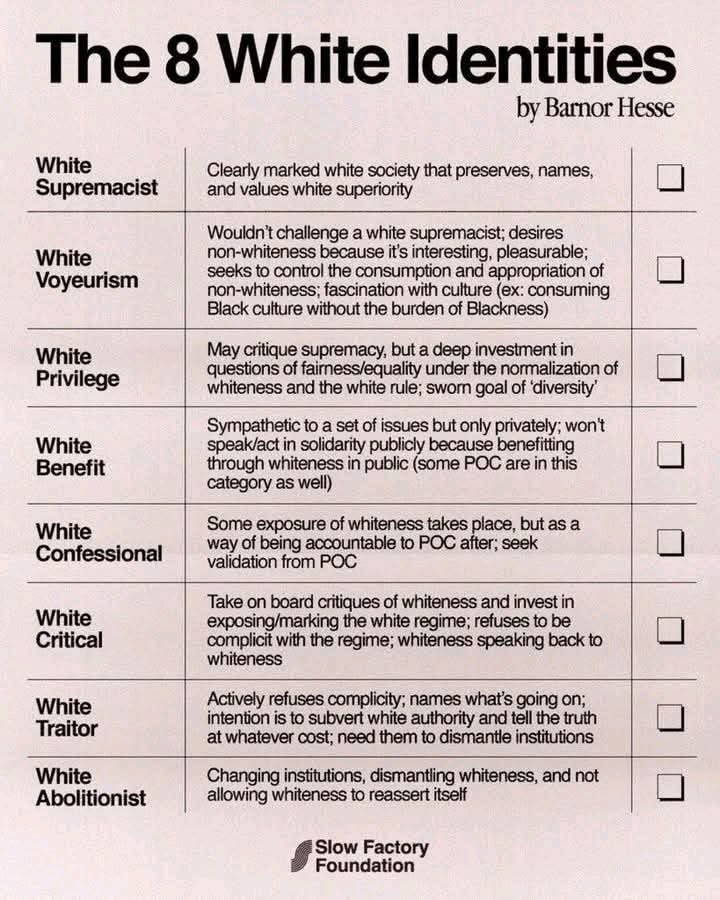

This “8 White Identities” chart (attributed to Barnor Hesse) looks like education, but it functions like a moral sorting machine. It offers eight labels that appear descriptive while quietly guiding you to one approved destination: “traitor/abolitionist,” meaning active participation in dismantling institutions so “whiteness” cannot “reassert itself.” That isn’t neutral analysis; it’s a disciplinary ladder. The key tell is the structure: most categories are not stable identities but staged accusations: if you don’t end at abolition, you’re still “benefiting,” “confessing,” “complicit,” or “voyeur.” It’s less “here are ways people relate to race” and more “here is your moral rank, move upward.”

Where does this method come from? In plain terms, it’s downstream of critical theory which is a family of approaches associated with the Frankfurt School, including Max Horkheimer, which treats social life as saturated with power and aims not merely to interpret society but to critique and transform it. Suspicion becomes the starting posture: norms, institutions, and “common sense” are read as mechanisms that reproduce domination. That posture can be illuminating when it identifies genuine structural incentives or hidden rules. The problem is what happens when the posture hardens into a closed moral cosmology: every institution is presumed guilty, every norm is presumed cover, and disagreement is presumed self-interest.

This particular pop-form is best described as CRT-style reasoning (even when it’s outside law schools): “whiteness” treated as an institutionalized advantage; disparities treated as presumptive evidence of systemic bias; “neutrality” treated as camouflage; and moral legitimacy tied to “anti-racist” alignment rather than truth-tracking. The flaw isn’t “not caring about racism.” The flaw is an a-historical compression: it collapses different eras, actors, and institutions into one continuous regime (“whiteness”) and treats complex tradeoffs as one moral story with one villain. You stop seeing plural motives, competing goods, and reformable failures; you see only complicity versus resistance.

The chart also relies on social coercion, not argument. It invites “accountability,” but what it means in practice is public performance under threat of moral demotion. Ask for evidence and you’re “centering yourself.” Disagree and you’re “invested.” Stay quiet and you’re “benefiting.” Even agreement becomes suspect if it’s the “wrong” kind (confessional, validation-seeking). That’s the unfalsifiable core: the framework is built so that any response can be converted into proof of guilt or complicity. A theory that cannot lose contact with counterevidence doesn’t guide understanding; it guides conformity.

If you actually want a model that helps rather than coerces, start with falsifiable claims and reformable mechanisms: identify specific policies, incentives, or gatekeeping practices; compare outcomes across institutions; test interventions; keep individual dignity intact; and treat moral status as something earned by conduct, not assigned by category. You can still talk about bias and history without turning identity into original sin. The danger of charts like this isn’t that they “teach empathy.” It’s that they train people to swap evidence for ritual, and dialogue for denunciation—and that trade makes every institution worse, not better.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article