You are currently browsing the monthly archive for May 2018.

If we have to live within a capitalist framework, the very least we can do is make sure everyone has a chance.

Helena de Bres writes about how Philosophy if you’re doing it right, is an absurd practice. What I found interesting about her essay is the idea of the two perspectives we shift between as hypothesized by Thomas Nagel (“One [perspective] is that of the engaged agent, seeing her life from the inside, with her heart vibrating in her chest. The other is that of the detached spectator, watching human activity coolly, as if from the distance of another planet.”). Us human types bring about so much of our own troubles, often failing to strike a reasonable balance between ‘living in moment’ and the detached ‘from the point of view of the Universe’. Significant life events, whether positive of negative, can also foment imbalance between these two perspectives, in which I think require careful mixing in order to live a more meaningful life.

One of the things I’ve noticed in the literature about grieving and loss is how important it is to realize the ubiquity of the experience that happens to be engulfing you at the moment. Most certainly, this is your own personal trauma, but realizing that others have and are experiencing similar feelings and going through similar motions can help frame your personal struggles in a slightly more hopeful context. For example, people have been grieving the loss of their loved ones for centuries now, and most find a way forward. There is some small solstice to be found (for the grieving person) in fact that others have found the means to go on after traumatic life experiences.

This contextual switching, I think, plays a significant role in the rebuilding of the emotional resilience that is necessary to keep life going and for an individual to continue to grow after a major setback. I see a fair number of parallels in this essay between the notion of dual experiential perspectives and some of the tenets of Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies.

“There’s something especially absurd about philosophers, supine or not. The explanation for this might lie in the best-known philosophical account of absurdity, offered by Thomas Nagel in 1971. Nagel argued that when we sense that something – or everything – in life is absurd, we’re experiencing the clash of two perspectives from which to view the world. One is that of the engaged agent, seeing her life from the inside, with her heart vibrating in her chest. The other is that of the detached spectator, watching human activity coolly, as if from the distance of another planet. Nagel notes that it’s our nature to flip between these points of view. One moment we’re fully caught up in our mushroom-cultivation class, our infatuation with our sister’s husband or our intractable power struggle with Terri in accounting. The next moment, our mental tectonics shift and we see ourselves from an emotional remove, like a spirit hovering over its own body. It becomes evident to us that, ‘from the point of view of the Universe’, to use the 19th-century utilitarian Henry Sidgwick’s phrase, none of these things matter.

Our sense of absurdity kicks in when we snap between these two perspectives rapidly, in a kind of duck-rabbit movement of the soul. The sense of absurdity depends on this instability. If we could retain the internal perspective forever, we’d never experience the shock of doubt about whether what we were doing was ultimately worthwhile or made any kind of sense. If, alternatively, we could permanently view all human affairs, our own included, from the perspective of the Universe, we’d never find ourselves eagerly attempting to adhere fungi to a damp log. We’d be full-time ascetics, to whom nothing human mattered at all, people who couldn’t be caught red-handed caring about something small.

Though Nagel says that we all adopt both the internal and external perspectives on our lives, some people clearly identify more with one than the other. And some of these people cluster in professions where one perspective is disproportionately valued. Academic philosophy is one such profession. When people say: ‘Let’s be philosophical about this,’ they mean: ‘Let’s calm down, step back, detach.’ The philosopher, in the public imagination, is set apart from the mundane concerns and fiery attachments that govern the rest of humanity. He or she takes the external perspective on pretty much everything. When Søren Kierkegaard collapsed at a party and people tried to help him up, he allegedly said: ‘Oh, leave it. Let the maid sweep it up in the morning.’

If this image is accurate, and if Nagel’s account is right, philosophers, parked forever in only one of Nagel’s perspectives, will escape the absurdity of the human condition. We philosophers, however, are among the most absurd people I’ve ever met. The reason for this has a whiff of paradox. Abstraction and detachment might be a philosopher’s stock-in-trade, but philosophers are often fiercely attached to those very things: passionate about impassion, abstract in the most concrete of ways. They spend years working obsessively on papers with titles such as ‘Nonreducible Supervenient Causation’ and then have public brawls about them at conferences. This is part of philosophy’s charm for me. There’s something especially absurd, yes, but also endearing, about people who are so serious about their core life endeavour that they regularly forget its ridiculous aspects, even though the endeavour itself is meant to serve as a perpetual reminder.”

Do you hear the people sing, singing the song of angry women? It is the music of a people that will not be slaves again! Go Ireland, Go Rights for Females. :)

Abortion - Abortion Clinics, Abortion Pill, Abortion Information

Ireland voted in a landslide to support abortion rights. But making abortion care available will take much more.

Charles McQuillan / Getty Images

To Isolde Carmody, Ireland’s overwhelming vote to repeal the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution was a vote to continue down the road that her great-grand-uncle, Joseph Plunkett, and his contemporaries fought for in 1916, in the first steps toward an independent Irish Republic.

“Joe was definitely a feminist, a revolutionary. He deeply believed…

View original post 2,460 more words

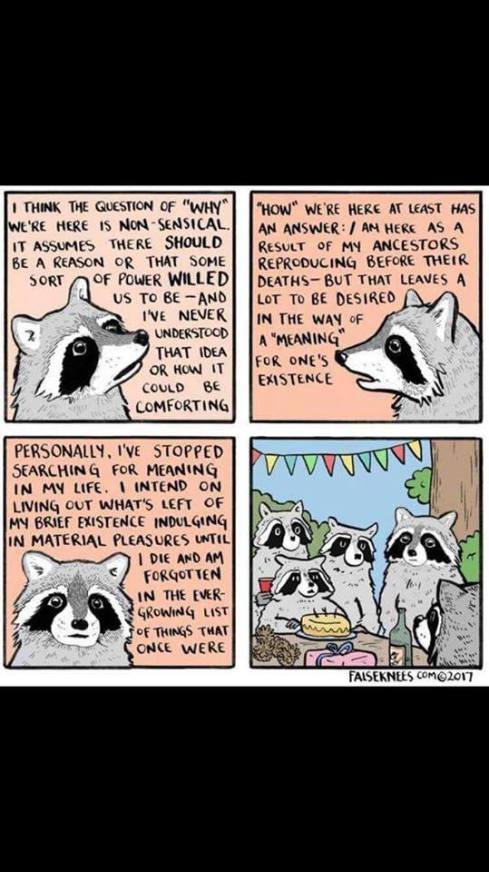

Hard truths from our furry trash-panda friends.

There are four lights…

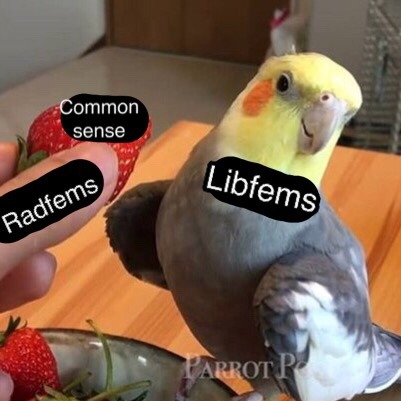

Your opinions…