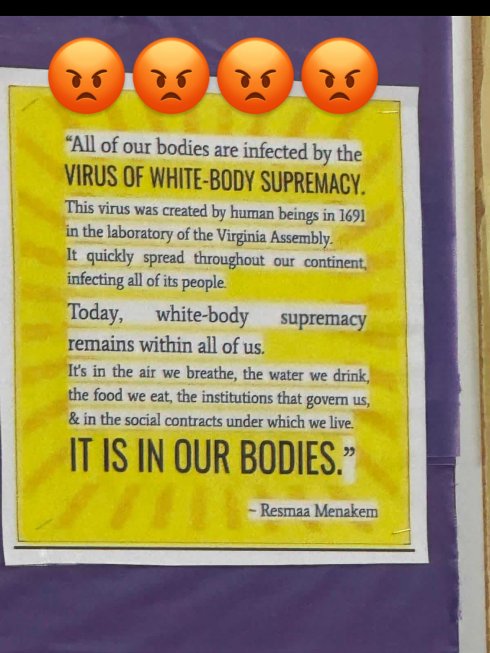

The poster’s quotation from Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands—a work on “somatic abolitionism”—masquerades as profound insight while peddling a corrosive myth: that white supremacy originated as a deliberate “virus” engineered in 1691 by the Virginia Assembly and now lives in every human body like an inescapable plague. This is not scholarship; it is narrative alchemy, transmuting concrete historical injustices into a metaphysical pathology that demands perpetual atonement from those deemed its carriers.

The verifiable record tells a different story. In 1691, the Virginia General Assembly did indeed enact a statute prohibiting interracial marriage and prescribing banishment for violators, declaring such unions “always to be held and accounted odious.” This and earlier laws—like the 1662 act establishing that a child’s enslaved status followed the condition of the mother—were instruments of economic control designed to stabilize a plantation system dependent on enslaved labor. They reflected cruelty and racial hierarchy, but to describe the Assembly as a “laboratory” that “created a virus” is to abandon historical analysis for political mythmaking.

Menakem’s metaphor extends beyond history into biological moralism. He claims the “virus of white-body supremacy” infects all people—Black, white, and otherwise—but insists that “white bodies” were its original vector. In doing so, his language transforms a moral failing into a physical contamination, pathologizing not actions or institutions but entire human beings. This rhetoric does not enlighten; it indicts an entire lineage for ancestral crimes, regardless of individual conscience or conduct.

The psychological consequence is predictable: self-loathing disguised as virtue. By teaching that “white bodies” are inherently supremacist, this ideology demands that people view their very physiology and heritage as polluted. It secularizes the ancient idea of inherited guilt, substituting ritual “somatic abolition” for redemption. The irony is tragic: the same civilization Menakem condemns also produced the philosophical and political revolutions—the Enlightenment, abolitionism, universal rights—that made slavery morally indefensible in the first place.

Finally, the metaphor corrodes civic trust. The Virginia Assembly, for all its failings, was also one of the earliest elected legislatures in the New World. To recast it as a “mad scientist’s lab” birthing a contagion of supremacy is to delegitimize the democratic experiment at its roots, suggesting that all institutions derived from it remain vectors of infection rather than imperfect vessels of self-correction and progress. Such thinking feeds cynicism, not justice, and erodes the moral foundations of the very equality it claims to seek.

Slavery and racial hierarchy were evils of human design, not biological inevitabilities. We honor truth by condemning those evils as moral and political wrongs—without collapsing into the superstition that guilt resides in the body or that redemption requires permanent contrition. The only real contagion here is the idea that identity determines virtue.

References

- Menakem, Resmaa. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

— Source of the “virus of white-body supremacy” metaphor and “laboratory of the Virginia Assembly” phrasing. - Hening, William Waller (ed.). The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619. Vol. 3. New York: R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823.

— Contains the 1662 and 1691 acts (“Act XII” of 1662 and “Act XVI” of 1691) establishing hereditary slavery and banning interracial marriage. - Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1975.

— Authoritative analysis of how race-based slavery evolved in colonial Virginia as a means of stabilizing class hierarchies. - Davis, David Brion. The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1966.

— Foundational work tracing slavery’s intellectual and moral contexts in Western thought. - Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

— Historical survey of the transformation from indentured servitude to race-based chattel slavery. - Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

— Explores the moral and political inheritance of the Virginia Assembly and the paradox of liberty coexisting with slavery. - Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1945.

— Classic defense of open inquiry and individual moral responsibility against collectivist and totalizing ideologies.

1 comment

Comments feed for this article

October 18, 2025 at 5:48 am

tildeb

This is a blood libel on display, which makes the poster statement itself absolutely pro racist. Slavery long predated 1691 across all races, and continues to this day especially in the Arab countries.

LikeLike