You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Economy’ category.

Canada is in the middle of a familiar temptation: the Americans are difficult, therefore the Chinese offer must be sane.

The immediate backdrop is concrete. On January 16, 2026, Canada announced a reset in economic ties with China that includes lowering barriers for a set number of Chinese EVs, while China reduces tariffs on key Canadian exports like canola. (Reuters) Washington responded with open irritation, warning Canada it may regret the move and stressing Chinese EVs will face U.S. barriers. (Reuters)

If you want a simple, pasteable bromide for people losing their minds online, it’s this: the U.S. and China both do bad things, but they do bad things in different ways, at different scales, with different “escape hatches.” One is a democracy with adversarial institutions that sometimes work. The other is a one-party state that treats accountability as a threat.

To make that visible, here are five egregious “hits” from each—then the contrast that actually matters.

Five things the United States does that Canadians have reason to resent

1) Protectionist trade punishment against allies

Steel/aluminum tariffs and recurring lumber duties are the classic pattern: national-interest rhetoric, domestic political payoff, allied collateral damage. Canada has repeatedly challenged U.S. measures on steel/aluminum and softwood lumber. (Global Affairs Canada)

Takeaway: the U.S. will squeeze Canada when it’s convenient—sometimes loudly, sometimes as a bureaucratic grind.

2) Energy and infrastructure whiplash

Keystone XL is the poster child of U.S. policy reversals that impose real costs north of the border and then move on. The project’s termination is documented by the company and Canadian/Alberta sources. (TC Energy)

Takeaway: the U.S. can treat Canadian capital as disposable when U.S. domestic politics flips.

3) Extraterritorial reach into Canadians’ private financial lives

FATCA and related information-sharing arrangements are widely experienced as a sovereignty irritant (and have been litigated in Canada). The Supreme Court of Canada ultimately declined to hear a constitutional challenge in 2023. (STEP)

Takeaway: the U.S. often assumes its laws get to follow people across borders.

4) A surveillance state that had to be restrained after the fact

Bulk telephone metadata collection under Patriot Act authorities became politically toxic and was later reformed/ended under the USA Freedom Act’s structure. (Default)

Takeaway: democracies can drift into overreach; the difference is that overreach can become a scandal, a law change, and a court fight.

5) The post-9/11 stain: indefinite detention and coercive interrogation

Guantánamo’s long-running controversy and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s reporting on the CIA program remain enduring examples of U.S. moral failure. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

Takeaway: the U.S. is capable of serious rights abuses—then also capable of documenting them publicly, litigating them, and partially reversing course.

Five things the People’s Republic of China does that are categorically different

1) Mass rights violations against Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang

The UN human rights office assessed serious human rights concerns in Xinjiang and noted that the scale of certain detention practices may constitute international crimes, including crimes against humanity. Canada has publicly echoed those concerns in multilateral statements. (OHCHR)

Takeaway: this is not “policy disagreement.” It’s a regime-scale human rights problem.

2) Hong Kong: the model of “one country, one party”

The ongoing use of the national security framework to prosecute prominent pro-democracy figures is a live, observable indicator of how Beijing treats dissent when it has full jurisdiction. (Reuters)

Takeaway: when Beijing says “stability,” it means obedience.

3) Foreign interference and transnational pressure tactics

Canadian public safety materials and parliamentary reporting describe investigations into transnational repression activity and concerns around “overseas police stations” and foreign influence. (Public Safety Canada)

Takeaway: the Chinese state’s threat model can extend into diaspora communities abroad.

4) Systematic acquisition—licit and illicit—of sensitive technology and IP

The U.S. intelligence community’s public threat assessment explicitly describes China’s efforts to accelerate S&T progress through licit and illicit means, including IP acquisition/theft and cyber operations. (Director of National Intelligence)

Takeaway: your “market partner” may also be running an extraction strategy against your innovation base.

5) Environmental and maritime predation at scale

China remains a dominant player in coal buildout even while expanding renewables, a dual-track strategy with global climate implications. (Financial Times)

On the oceans, multiple research and advocacy reports emphasize the size and global footprint of China’s distant-water fishing and associated IUU concerns. (Brookings)

Takeaway: when the state backs extraction, the externalities get exported.

Compare and contrast: the difference is accountability

If you read those lists and conclude “both sides are bad,” you’ve missed the key variable.

The U.S. does bad things in a system with adversarial leak paths:

investigative journalism, courts, opposition parties, congressional reports, and leadership turnover. That doesn’t prevent abuses. It does make abuses contestable—and sometimes reversible. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

China does bad things in a system designed to prevent contestation:

one-party rule, censorship, legal instruments aimed at “subversion,” and a governance style that treats independent scrutiny as hostile action. The problem isn’t “China is foreign.” The problem is that the regime’s incentives run against transparency by design. (Reuters)

So when someone says, “Maybe we should pivot away from the Americans,” the adult response is:

- Yes, diversify.

- No, don’t pretend dependency on an authoritarian state is merely a swap of suppliers.

A quick media-literacy rule for your feed

If a post uses a checklist like “America did X, therefore China is fine,” it’s usually laundering a conclusion.

A better frame is risk profile:

- In a democracy, policy risk is high but visible—and the country can change its mind in public.

- In a one-party state, policy risk is lower until it isn’t—and then you discover the rules were never meant to protect you.

Canada can do business with anyone. But it should not confuse trade with trust, or frustration with Washington with safety in Beijing.

If Canada wants autonomy, the answer isn’t romanticizing China. It’s building a broader portfolio across countries where the rule of law is not a slogan in a press release.

References

- Canada–China trade reset (EV tariffs/canola): Reuters; Guardian. (Reuters)

- U.S. criticism of Canada opening to Chinese EVs: Reuters. (Reuters)

- U.S. tariffs/lumber disputes: Global Affairs Canada; Reuters. (Global Affairs Canada)

- Keystone XL termination: TC Energy; Government of Alberta. (TC Energy)

- FATCA Canadian challenge result: STEP (re Supreme Court dismissal). (STEP)

- USA Freedom Act / end of bulk metadata: Lawfare; Just Security. (Default)

- CIA detention/interrogation report: U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee report PDF. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

- Guantánamo context: Reuters; Amnesty. (Reuters)

- Xinjiang assessment: OHCHR report + Canada multilateral statement. (OHCHR)

- Hong Kong NSL crackdown example: Reuters (Jimmy Lai). (Reuters)

- Transnational repression / overseas police station concerns: Public Safety Canada; House of Commons report PDF. (Public Safety Canada)

- China tech acquisition / IP theft framing: ODNI Annual Threat Assessment PDF. (Director of National Intelligence)

- Coal buildout: Financial Times; Reuters analysis. (Financial Times)

- Distant-water fishing footprint / IUU concerns: Brookings; EJF; Oceana. (Brookings)

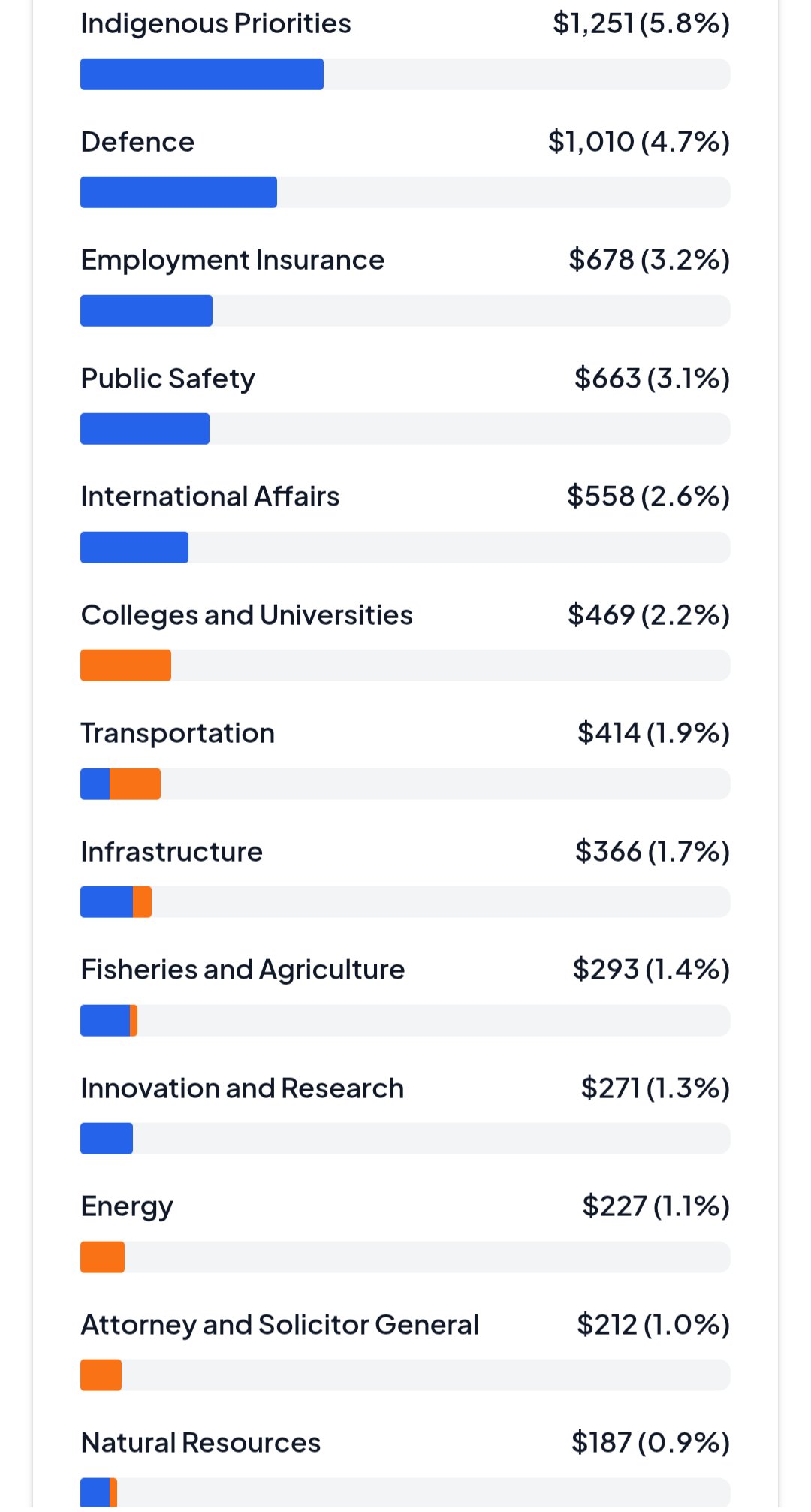

Canada’s federal budget tells a story that few seem willing to read critically. According to CanadaSpends.com, Ottawa allocates $1.251 billion—5.8 percent of the budget—to “Indigenous Priorities,” eclipsing even Defence ($1.010 billion, 4.7 percent). The arithmetic alone invites scrutiny. At what point does reconciliation become a fiscal reflex, untethered from measurable outcomes?

The Arithmetic of Imbalance

Consider a simple exercise in opportunity cost. Halving “Indigenous Priorities” to $625.5 million would free an equal amount—$625.5 million—for redeployment elsewhere. Redirecting that sum to Public Safety, currently $663 million (3.1 percent), would nearly double its capacity to $1.288 billion. The outcome: stronger policing resources, reinforced border security, and potentially measurable reductions in crime—objectives grounded in deterrence rather than symbolism.

This is not an argument against Indigenous advancement. It is an argument for proportionality and accountability. “Indigenous Priorities” now consume more than Employment Insurance ($678 million), International Affairs ($558 million), and Colleges and Universities ($469 million) combined. Defence, tasked with national sovereignty, trails by $241 million. When cultural or consultative programs eclipse citizen security and education, something in our fiscal compass is misaligned.

The Accountability Deficit

Proponents will cite historical redress, and that moral claim has force. But truth in budgeting requires evidence, not sentiment. Where are the audited outcomes showing that each billion spent yields measurable gains in Indigenous health, education, or economic independence?

The problem is not merely bureaucratic inertia—it is structural opacity, worsened by political choice. In December 2015, the newly elected Liberal government suspended enforcement of the First Nations Financial Transparency Act, which had required Indigenous governments to publish audited financial statements and leadership salaries. The minister at the time, Carolyn Bennett, directed her department to “cease all discretionary compliance measures” and reinstated funding to communities that refused disclosure.

In effect, Ottawa dismantled the only system ensuring public visibility into how billions of tax dollars are spent. Nearly a decade later, the Auditor General’s 2025 report found “unsatisfactory progress” on more than half of all Indigenous-services audit recommendations, despite an 84 percent increase in program spending since 2019. The data are undeniable: accountability has eroded even as expenditures have soared.

Fiscal Compassion, Not Fiscal Indulgence

Canada does not need less compassion; it needs measurable compassion—spending that demonstrably improves lives rather than perpetuates dependency. Halving the current Indigenous Priorities budget would not abolish support or reverse reconciliation. It would introduce accountability, allowing funds to be reallocated to public safety, infrastructure, or innovation—areas with immediate and empirically verifiable benefits.

Until Indigenous programs are evaluated with the same rigour applied to defence, education, or social insurance, billion-dollar gestures will remain ends in themselves—virtue without verification.

References

- CanadaSpends.com – Federal Tax Visualizer

- Government of Canada Statement on the First Nations Financial Transparency Act (2015)

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2025 Report – Programs for First Nations

- Canadian Affairs News – Poll: Canadians Want Transparency in First Nations Finances (2025)

- Standing Committee Appearance: Supplementary Estimates (2024)

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2023–24 Results Report

Poland’s ascent to a $1 trillion economy in September 2025 marks a remarkable transformation. Emerging from the wreckage of Soviet control, Poland has become one of Europe’s fastest-growing economies over the past three decades. With GDP growth projected at 3.2 percent for 2025, unemployment near 3 percent (harmonized), and inflation moderating to 2.8 percent in August, it demonstrates resilience and steady progress.

Canada, with a nominal GDP of roughly $2.39 trillion, is richer in absolute terms but faces weaker dynamics: growth forecasts of just 1.2 percent, unemployment climbing to 7.1 percent in August, and persistent concerns over productivity and rising public debt. The contrast raises an important question: which elements of Poland’s success can Canada responsibly adapt to its own very different circumstances?

1. Manufacturing Capacity and Industrial Resilience

Poland’s economy has benefited from retaining a strong industrial base, especially in automotive, machinery, and technology supply chains closely integrated with Germany. This foundation has provided steady export growth and employment, while limiting excessive reliance on fragile overseas supply chains.

Canada, by contrast, has seen its manufacturing share of GDP shrink over decades as industries relocated or hollowed out. While Canada cannot replicate Poland’s role as a mid-cost hub inside the EU, it could adapt the principle: incentivize the repatriation or expansion of high-value sectors (e.g., EV manufacturing, critical minerals processing, aerospace). Strategic tax credits, infrastructure investment, and streamlined permitting could restore resilience and provide middle-class employment.

Lesson for Canada: industrial renewal need not mean autarky, but building domestic capacity in key sectors reduces vulnerability to shocks — as Poland’s stability during recent European crises shows.

2. Immigration Policy and Integration Capacity

Poland has pursued a relatively selective immigration system, prioritizing labor market fit and manageable inflows. While Poland remains relatively homogeneous (Eurostat estimates about 98% ethnic Polish in 2022), its policy has focused on ensuring newcomers integrate into economic and cultural life. The result has been high employment among migrants and limited social disruption compared with some Western European peers.

Canada, by contrast, accepts large inflows — even after scaling back targets to 395,000 permanent residents in 2025 — and faces housing pressures and uneven integration outcomes. Canada’s homicide rate (2.27 per 100,000 in 2022) is higher than Poland’s (0.68), though crime is shaped by many factors beyond immigration. Still, rapid population growth without infrastructure, housing, and language capacity has heightened social strains.

Lesson for Canada: immigration policy should balance humanitarian goals with absorptive capacity. Emphasizing labor alignment, regional settlement, and language proficiency — as Poland has done — would help ensure inflows strengthen productivity while minimizing stress on housing and services.

3. Cultural Continuity and Heritage as Assets

Poland has paired modernization with deliberate protection of its cultural identity. The restoration of Kraków and Warsaw not only preserves heritage but fuels a thriving tourism sector. National traditions, rooted in Catholicism for many Poles, have also informed family policy (e.g., child benefits) and provided a sense of cohesion during rapid economic change.

Canada’s pluralism differs fundamentally, and it cannot — and should not — mimic Poland’s religious or cultural model. Yet Canada can still learn from the broader principle: treating heritage and shared narratives as economic and social assets rather than obstacles. Investments in Indigenous landmarks, Francophone culture, and historic architecture could enrich tourism, foster pride, and strengthen cohesion. Likewise, family-supportive policies (parental leave, child benefits, flexible work arrangements) are essential as Canada faces declining fertility and an aging workforce.

Lesson for Canada: cultural preservation and demographic support are not nostalgic luxuries — they can reinforce economic stability and social cohesion.

4. Fiscal Prudence and Monetary Autonomy

Poland’s choice to retain the zloty rather than adopt the euro preserved monetary flexibility. Combined with relatively conservative fiscal policies (public debt at about 49% of GDP in 2024, well below EU ceilings), this has allowed Poland to respond to crises with agility while maintaining competitiveness.

Canada already benefits from its own currency, but fiscal expansion has pushed federal debt above 65% of GDP. While Canada’s wealth affords greater borrowing room, long-term sustainability requires discipline. Poland’s experience suggests that debt caps, counter-cyclical saving, and careful monetary coordination can preserve resilience without stifling growth.

Lesson for Canada: fiscal credibility is itself an economic asset. Setting clearer debt-to-GDP targets and enforcing discipline would strengthen Canada’s ability to weather global volatility.

Conclusion

Poland’s trajectory is not without challenges. It faces demographic decline, reliance on EU subsidies, and governance controversies that Canada would not wish to replicate. But its achievements underscore a vital truth: prosperity need not mean sacrificing resilience, identity, or cohesion.

For Canada, the actionable lessons are clear:

-

rebuild key industries,

-

align immigration with integration capacity,

-

invest in heritage and families,

-

and re-anchor fiscal policy in prudence.

Adapted to Canadian realities, these reforms could help lift growth closer to 3 percent, reduce unemployment, and restore a sense of national momentum.

References

-

International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Database, October 2025.

-

Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey, August 2025.

-

Eurostat. Population Structure and Migration Statistics, 2022–2025.

-

OECD. Economic Outlook: Poland and Canada, 2025.

-

World Bank. World Development Indicators, 2024–2025.

-

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Homicide Statistics, 2022.

-

National Bank of Poland. Annual Report, 2024.

-

Government of Canada. Immigration Levels Plan 2025–2027.

When a government spends beyond its means, citizens eventually pay the price. This reality looms over Prime Minister Marc Carney’s fiscal approach, which has drawn mounting criticism for being both irresponsible and inflationary. With federal spending ballooning under his leadership, Canada faces mounting deficits that risk fueling long-term inflation and undermining economic stability.

At its core, Carney’s fiscal strategy rests on aggressive public expenditure with the stated aim of stimulating growth and addressing social inequities. While such intentions may sound noble, the result is the same problem that has plagued countless governments before: spending outstrips revenue, and deficits grow. Canada is already burdened with significant debt from past administrations, and Carney’s unwillingness to rein in spending threatens to push the nation further into the red. This raises serious concerns about the sustainability of his policies.

The inflationary risks cannot be overstated. When governments flood the economy with borrowed money, demand rises artificially, often faster than supply can keep up. The outcome is predictable: rising prices that erode the purchasing power of ordinary Canadians. Carney’s background as a central banker makes his freewheeling fiscal approach especially puzzling, given that he fully understands how unchecked deficits translate into inflationary pressures. By ignoring these basic economic principles, he risks not only undermining Canadian competitiveness but also hollowing out the middle class he claims to champion.

The consequences of such policies ripple outward. Inflation means higher food and housing costs, disproportionately hurting working families. Higher deficits translate into heavier debt servicing, which steals resources from essential services like healthcare and infrastructure. In short, Carney’s fiscal vision looks less like a plan for prosperity and more like a reckless gamble with the nation’s future.

Table: Why Carney’s Fiscal Policies Risk Inflation

| Policy/Action | Short-Term Effect | Long-Term Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive public spending | Temporary economic stimulus | Rising deficits and debt burden |

| Borrowing to finance programs | Increased demand | Inflationary pressure and weakened currency |

| Ignoring fiscal restraint | Boosts political popularity | Erodes economic competitiveness |

| Large deficits | Expanded government footprint | Reduced fiscal flexibility in future crises |

| Reliance on debt-financed growth | Superficial prosperity | Declining middle-class purchasing power |

References

- Canada’s Budget Deficit First Four Months 2025/26 — Between April-July 2025 the federal deficit rose to C$7.79 billion, as spending grew faster (3.0%) than revenues (1.6%). (Reuters)

- Deficit Estimate for Entire Fiscal Year — Economists project Canada’s 2025-26 deficit could hit C$70 billion, more than the previous year’s (approx. C$48 billion). (TT News)

- Government Spending Rise — 2025-26 federal main estimates show total spending of C$486.9 billion, an 8.4% increase from the previous year. (iPolitics)

- Projected Future Deficits — Carney’s platform projects yearly deficits of ~C$62 billion in 2025-26, dropping gradually in following years but still significant. (Taxpayer)

- Deficit Pressure from Trade War & Tariffs — U.S. tariffs and counter-tariffs affecting revenues and costs are cited as one factor expected to increase deficits well above initial forecasts. (The Hub)

- Official Signalling of Higher Deficit — Ottawa has publicly acknowledged that the upcoming budget will feature a “substantial” deficit, larger than last year’s, and has warned that all departments must participate in spending restraint efforts. (Global News)

Canada’s tariff wars reveal a glaring double standard: confrontation with Communist China draws muted shrugs, while disputes with the United States ignite fiery “elbow up” rhetoric and national outrage. When China slapped a 75.8% tariff on Canadian canola in August 2025—retaliation for Ottawa’s 100% tariff on Chinese electric vehicles and 25% on steel and aluminum announced earlier that spring—Manitoba farmers were left reeling. Nearly half of their canola exports go to China, and industry estimates project multi-billion-dollar losses. Yet Canada’s political class and major media outlets framed Beijing’s move as a mere “tit-for-tat” trade dispute, urging patience and diplomacy. Outside the mainstream, social media filled with posts lamenting the devastation in farm country.

Contrast this with the uproar over U.S. tariffs. In March 2025, President Donald Trump imposed 25% duties on Canadian goods (excluding energy), escalating them to 35% by August. Ottawa erupted. Prime Minister Mark Carney thundered about the need for a unified “North American market,” while pundits and media outlets blasted “unjustified” American aggression. Canadians were rallied with slogans of defiance and “elbow up” resolve. Yet under CUSMA, more than 85% of Canada–U.S. trade remains tariff-free, meaning the outrage over Washington’s measures dwarfed the reaction to China’s far heavier blow to canola.

The contrast betrays selective indignation. China, an authoritarian regime, cripples a vital Canadian industry yet escapes national fury. The United States, a democratic ally, delivers a lesser economic hit and is vilified. Such narrative hypocrisy undermines both unity and credibility, sacrificing farmers’ livelihoods for geopolitical posturing. If Canada roars at Washington but bows to Beijing, it sends a dangerous message: principle is negotiable, and farmers are expendable.

Sources:

-

Statistics Canada, 2023 Trade Data

-

CBC News, “China’s Tariffs on Canadian Canola,” Aug. 13, 2025

-

Fraser Institute, “Trump’s Trade War Update,” Aug. 12, 2025

-

Globe and Mail, “Over 85% of Canada–U.S. Trade Remains Tariff-Free under CUSMA,” Aug. 2025

-

Aggregated X posts, Aug. 2025

Inflation is the steady climb in prices for goods and services, shrinking what your money can buy over time. It arises when too much money chases too few goods, a dynamic fueled by policy missteps and economic shocks. This essay examines inflation’s primary drivers, emphasizing government spending and money printing, with a focus on Canadian examples, including recent actions, grounded in hard evidence. The stakes are high: inflation corrodes savings, disrupts planning, and frays societal unity, demanding a clear-eyed look at its causes.

Government spending, especially when deficit-financed, is a key inflationary culprit. Large-scale fiscal interventions—like Canada’s $500 billion in COVID-19 relief programs in 2020–2021, including the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)—flooded the economy with cash, spiking demand. This surge, coupled with supply constraints, drove Canada’s inflation to 8.1% in June 2022, a 40-year high. A 2022 Scotiabank analysis estimated these programs added 0.45 percentage points to core inflation by widening the output gap. Historically, Canada’s 1970s deficit spending, which fueled double-digit inflation, mirrors this pattern. Recent policies, such as 2025 provincial and federal inflation-relief transfers, risk further stoking demand, with Scotiabank projecting they could necessitate a 38% share of the Bank of Canada’s rate hikes to counteract their inflationary impulse.

Money printing, through central bank policies like quantitative easing, devalues currency by expanding the money supply. In Canada, the Bank of Canada’s purchase of $400 billion in government bonds during 2020–2021 lowered interest rates to 0.25%, encouraging spending but devaluing the Canadian dollar. This imported inflation, as a weaker dollar raised import costs, contributing over 50% to inflation in final domestic demand by late 2022. Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation in the 2000s, peaking at 79.6 billion percent monthly, offers an extreme parallel, driven by unchecked money creation. In 2024, the Bank of Canada’s continued quantitative tightening, alongside a 2025 policy rate hold at 4.5%, reflects efforts to curb these pressures, though global factors like U.S. inflation still amplify Canada’s import-driven price hikes.

Supply shocks and wage-price spirals further aggravate inflation. Canada’s 2022 supply chain disruptions, exacerbated by global port delays and China’s COVID-zero policy, spiked food and energy prices—food alone contributed 1.02 percentage points to inflation. The 1973 OPEC embargo, which quadrupled oil prices, offers a historical parallel, as does Canada’s 2022 experience with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which drove gasoline prices to $2 per liter. Wage-price spirals, fueled by 4.5% wage growth in advanced economies in 2021, also played a role, with Canada’s labor shortages post-reopening pushing service prices up 5% by mid-2022. Current U.S. tariffs on Canadian goods, as of January 2025, threaten to raise import costs further, with uncertain pass-through to consumers, potentially sustaining inflationary pressure.

Inflation’s corrosive grip—evident in Canada’s 2022 peak and lingering 2.6% rate in February 2025—demands accountability. Government spending and money printing, as seen in Canada’s pandemic policies and bond purchases, are potent drivers, amplified by supply shocks and wage dynamics. Historical and recent evidence, from 1970s deficits to 2025 tariff risks, underscores the need for disciplined fiscal and monetary policy. Citizens must demand restraint to protect purchasing power and preserve economic stability before inflation’s tide engulfs us all.

Bibliography

- Congressional Budget Office. (1980). The Economic Effects of Federal Deficits. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/21925

- Energy Information Administration. (1974). Historical Overview of the 1973 Oil Crisis. https://www.eia.gov/history/

- European Central Bank. (2019). Asset Purchase Programmes. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html

- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (2021). Fiscal Policy and Excess Inflation During the Pandemic. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2021/may/fiscal-policy-and-excess-inflation-during-pandemic/

- International Monetary Fund. (2009). Zimbabwe: Hyperinflation. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Zimbabwe-Hyperinflation-22603

- OECD. (2022). Employment Outlook 2022. https://www.oecd.org/economy/employment-outlook/

- Scotiabank. (2022). Canadian Inflation: Mostly Temporary and Foreign, But Pandemic Programs Have a Major Impact on Policy Rates. https://www.scotiabank.com

- Statistics Canada. (2024). High Inflation in 2022 in Canada: Demand–Pull or Supply–Push?. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca

- The Globe and Mail. (2022). The Most Important Source of Canada’s Inflation: The Government Borrowed More Than $700-Billion. https://www.theglobeandmail.com

Your opinions…