You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Education’ category.

[This is second in an expository series on how “Woke” works, see here for the foundational essay on what woke is]

1) The claim

“Woke” is not a single policy or a stable tribe. It is a portable political form: a way of converting friction into identity, and identity into a special way of knowing.

A practical diagnostic:

- Ontological grievance: the dispute becomes about who we are and what is being done to us.

- Positional knowing: standing determines what can be known; dissent becomes suspect.

- Self-sealing loop: objections are reinterpreted as proof of corruption.

When those stack, persuasion decays into control-seeking.

2) The Left, steelmanned (and where the machine bites)

Start with the best version. There are reasonable claims on the Left:

- Institutions can have blind spots that matter in real lives.

- Listening to marginal voices can correct systematic inattention.

- Some norms exclude people unnecessarily, and reform can reduce that.

That’s ordinary liberal reform.

Machine activation begins when “correction” turns into “jurisdiction.” Disagreement becomes “harm,” procedural neutrality becomes “violence in disguise,” and the argument becomes uncorrectable because argument itself is reclassified as aggression.

You can see the pattern in soft-power settings where programming becomes legitimacy warfare. The Adelaide Writers’ Week / Randa Abdel-Fattah controversy escalated into resignations, withdrawals, cancellation, institutional apology, and a promised reinvitation. The conflict stopped being “who should speak” and became “who has moral authority to decide who speaks.” (ABC)

Now the policy-adjacent version (harder, more consequential): Canada’s Bill C-9 (Combatting Hate Act). Steelman: protecting people’s access to religious/cultural spaces from intimidation and addressing hate-motivated conduct are serious public-order aims. (Canada)

But the same machine-shaped risk appears in the surrounding rhetoric: once “speech boundary” disputes are treated as a moral sorting test (good people vs haters), it becomes harder to argue about scope, definitions, and safeguards without being read as suspect. Civil-liberties groups explicitly warn about Charter impacts and overreach risks. (CCLA)

The point is not “hate laws are woke.” The point is: when moral urgency turns into epistemic privilege, the debate stops being corrigible.

3) The Right, steelmanned (and where the machine bites)

Start with the best version. There are reasonable claims on the Right:

- Borders, civic trust, and state capacity matter.

- Institutions sometimes overreach and launder ideology through “neutral” language.

- Recent years have trained people to doubt official narratives too easily.

That is not conspiracism. It’s ordinary suspicion in a messy age.

Bridge sentence (the crucial distinction): distrust becomes machine-shaped when it flips into a total explanatory key, where suppression itself is treated as evidence of truth (“they don’t want you to know”), and disagreement is recoded as complicity.

That’s the turn that makes replacement-style narratives so sticky: anxiety about cohesion gets converted into a unified dispossession story with hidden directors. Watchdogs and explainer sources describe “Great Replacement” ideology as a white nationalist conspiracy frame, often with antisemitic variants, and as a driver for radicalization. (Al Jazeera)

(One more steelman note: people can argue about immigration levels, integration, and public confidence without endorsing any of that. The machine is not “caring about borders.” The machine is the sealed metaphysics move.)

4) Shared outputs (what the form produces on either side)

Once the form locks in, the outputs converge:

Friend–enemy sorting

People are judged less by arguments than by whether they accept the frame. “Ally” becomes an obedience category.

Exception ethics

Rules become “context.” Double standards become “justice.” Coercion becomes “self-defense.”

Platform war

Institutions become terrain: universities, HR offices, granting bodies, publishers, professional colleges.

A Canadian micro-case: the York University Student Centre dispute around MP Garnett Genuis shows how a procedural venue decision can become a symbolic censorship war, with different accounts emphasizing policy requirements versus ideological suppression. The ambiguity itself becomes fuel. (CityNews Edmonton)

5) The discriminator (reform vs machine)

Reform politics says: we can be wrong; show what would change our mind.

Machine politics says: disagreement proves you are contaminated.

That shift is the warning. Not that every Left claim is woke, or every Right claim is woke, but that any movement becomes uncorrigible once it adopts the form.

When that happens, societies stop arguing and start purging. 🧯

Glossary

- Ontological grievance: a complaint treated as core to being, not a fixable dispute.

- Positional knowing / standpoint: the view that social position determines access to truth; some “lived experience” claims function as trump cards.

- Self-sealing loop: a reasoning loop where objections become confirmation.

- Friend–enemy sorting: political classification that treats opponents as existential threats.

- Exception ethics: moral rules are suspended because “we’re under siege.”

- Platform war: institutions become the main battleground for power.

- Corrigible: open to correction by evidence and argument.

Endnotes

- James Lindsay, “What Woke Really Means” (New Discourses podcast, Jan 21, 2026).

- Adelaide Writers’ Week controversy: ABC coverage and Adelaide Festival statement (apology + 2027 reinvitation), plus reporting on cancellation after withdrawals. (ABC)

- Bill C-9 (Combatting Hate Act): Government summary + bill text; civil-liberties critiques and legal-professional analysis. (Canada)

- York University Student Centre / Garnett Genuis dispute (policy vs free-speech framing). (CityNews Edmonton)

- “Great Replacement” explainer coverage describing it as a conspiracy frame and discussing radicalization risk. (Al Jazeera)

Attribution: This essay is a paraphrase-and-critique prompted by James Lindsay’s New Discourses Podcast episode “What Woke Really Means.” Any errors of interpretation are mine. (New Discourses)

“Woke” is a word that now means everything and nothing: insult, badge, shibboleth, brand. That’s why it’s worth defining it narrowly before arguing about it. I’m not using “woke” to mean “progressive,” “civil-rights liberal,” “any activism,” or “anyone who thinks injustice exists.” I mean a specific machine: a moral–political pattern that turns social friction into group-based identity, and then turns group-based identity into a special way of knowing. When that pattern is present, the downstream politics are unusually predictable.

The first engine is entitlement turned into alienation. Start with a felt ought: people like me should be able to live, speak, belong, succeed, and be recognized in a certain way. That ought can be reasonable. Some groups really have been locked out of full participation. Institutions really do gatekeep. Norms really do punish outsiders. The pivot is what you do with the mismatch between “ought” and reality. The woke machine teaches that the mismatch is not mainly a mix of tradeoffs, chance, imperfect policy, individual bad actors, or local failures. It is alienation, a structural condition imposed by an illegitimate power arrangement. Your frustration is not merely about outcomes. It becomes about being denied your proper mode of existence. Once alienation is framed that way, it stops being a problem to solve and becomes an identity to inhabit.

That identity shift is the real move. The self is quietly demoted from “individual with rights and duties” to “representative of a class in conflict.” You begin to think in group nouns first: oppressed/oppressor, marginalized/privileged, normal/deviant, colonized/colonizer. This is why identity politics shows up so reliably. It is a downstream output of a prior decision to interpret the world through group-alienation. It can even masquerade as humility. “I’m just listening to marginalized voices.” But it performs a different operation. Moral standing relocates from argument to position. You don’t merely hold beliefs. You become a bearer of a collective grievance, and that grievance grants a kind of authority in advance.

The second engine is epistemic: knowledge becomes positional. Again, the starting observation can be true enough. Institutions reward certain ways of speaking. Credentialing filters who gets heard. Consensus is sometimes wrong. Lived experience can surface facts that statistics miss. The woke machine turns those observations into a total explanation. The established “knowing field” is not just fallible, but hegemonic. It is treated as a knowledge regime that functions to protect power.

There is an honest version of this impulse. Marginalized people can notice things insiders miss. Testimony can expose local abuses that institutions quietly normalize. Suspicion of official narratives is sometimes warranted. History is full of respectable consensus that later looks like rationalized cruelty. In that sense, privileging marginalized voices can function as a corrective. The problem begins when “corrective” hardens into a standing hierarchy of credibility, and when the moral value of hearing becomes a substitute for the epistemic work of checking. At that point, the method stops being a tool for truth and becomes a tool for power.

Once you accept the hegemonic frame as total, a standing preference follows. “Counter-hegemonic” claims, those said to come from the margins or said to be suppressed, are treated as inherently more trustworthy, or at least more morally protected. The point isn’t always truth. Often it’s leverage. If a claim destabilizes the legitimacy of the system, it gets treated as epistemically special.

You can see how this becomes self-sealing. Consider a common pattern: demographic observation, then a moralized system interpretation, then an appeal to lived experience, then immunity from counterargument. “I notice a space is mostly white.” Fine. “Therefore hiking is racist.” That is not observation but diagnosis. If challenged, the claim can retreat into experience: “I feel unsafe,” “my lived experience says otherwise.” Any dissent is then reclassified as proof of the system’s blindness. The disagreement is not processed as information. It becomes further evidence of hegemony. At that point, you’re no longer arguing about the world. You’re litigating the moral status of who gets to describe it.

Put these two engines together, alienation-as-identity and positional knowing, and the political outputs stop looking like random bad behavior. If your group’s situation is existential, ordinary ethics begin to look like luxuries written by your enemy. Double standards don’t feel like hypocrisy. They feel like “context.” Coercive tactics don’t feel like power-seeking. They feel like self-defense. “Allies” become morally sorted people who accept the frame. “Enemies” become those who refuse it. Because the machine treats knowledge as power, controlling speech and institutions can be rationalized as protecting truth rather than enforcing conformity.

So here’s a clean diagnostic that avoids cheap mind-reading. It’s not “woke” to notice injustice, organize, protest, or advocate. It becomes woke in this sense when three conditions appear together:

- Ontological grievance: your primary identity is a group-based injury story. Who you are is mainly who harmed “your people.”

- Positional epistemology: the status of a claim depends heavily on who says it, not what can be shown. Identity outranks argument.

- Self-sealing reasoning: disagreement is treated as proof of harm or hegemony, making correction impossible.

Any one of these can show up in ordinary politics. “Woke,” in this narrow sense, is when they lock together and become a stable identity system.

That triad is the machine. Once it’s operating, it tends to erode the conditions that let pluralistic societies function: shared standards of evidence, equal moral agency, and the ability to disagree without being treated as morally contaminated. In its best moments, the impulse can push institutions to see what they ignored and to repair what they excused. But a politics that begins as reform can slide into a politics that needs conflict as fuel. Once conflict becomes fuel, the temptation is obvious. Keep the wound open. Keep the epistemic gate locked. Keep the enemy permanent. If the machine ever stops, the identity it built starts to dissolve. 🔥

Glossary 📘

Alienation

A felt separation from what you believe you should rightfully be or have. In this framework: not mere disappointment, but a condition allegedly imposed by an illegitimate system.

Entitlement claim

A “felt ought”: a belief that people like me (or my group) are owed a certain kind of recognition, access, or outcome. Not automatically “spoiled,” just the moral premise that something is due.

Group-based identity

A primary self-concept built around membership in a social category (race/sex/class/nation, etc.), especially when that category is framed as locked in conflict with another.

Identity politics

Politics organized primarily around group membership and group conflict rather than individual rights, shared citizenship, or policy compromise.

Ontology / ontological grievance

Ontology is “what you are.” Ontological grievance is when grievance becomes core to being: the self is primarily defined as an injured member of an alienated group.

Epistemology / positional epistemology

Epistemology is “how we know.” Positional epistemology is when the credibility of claims depends heavily on the speaker’s identity position, rather than evidence and argument.

Hegemony / hegemonic knowledge

The idea that a society’s “common sense” and official knowledge are shaped to preserve existing power. “Hegemonic knowledge” is what the system allegedly allows as legitimate truth.

Counter-hegemonic / marginalized claims

Claims presented as outside the dominant “knowing field,” often treated as morally protected or more trustworthy because they challenge the status quo.

Lived experience

First-person testimony about what life is like. Valuable as evidence of experience; controversial when treated as unquestionable authority on broad causal explanations.

Self-sealing reasoning

A reasoning pattern where counterevidence is reinterpreted as evidence for the claim (for example, “your disagreement proves the system’s bias”), making the claim hard to correct.

Friend–enemy politics

A posture that sorts people into allies and enemies in a moralized way, where dissent feels like threat rather than disagreement.

Exception ethics

A moral logic where ordinary standards like fairness, consistency, and procedural restraint are suspended because the situation is framed as existential.

Endnotes

- James Lindsay, “What Woke Really Means,” New Discourses Podcast (New Discourses, January 21, 2026). (New Discourses)

- “What Woke Really Means,” New Discourses (audio hosting/episode metadata). (SoundCloud)

- Joe L. Kincheloe, Critical Constructivism Primer (Peter Lang, 2005). (Peter Lang)

- Özlem Sensoy and Robin DiAngelo, Is Everyone Really Equal? An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education, 2nd ed. (Teachers College Press, 2017). (tcpress.com)

- Helen Pluckrose and James A. Lindsay, Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody (Pitchstone Publishing, 2020). (ipgbook.com)

Modern psychology has a recurring weakness. It periodically falls in love with stories that feel morally urgent, then struggles to unwind them when the evidence turns out thin. That is not because psychologists are uniquely foolish. It is because the field studies messy human beings with noisy measures, ambiguous constructs, and strong social incentives. In that environment, a persuasive narrative can get promoted into “settled science” long before it is actually settled.

The replication crisis is the clearest public sign of this vulnerability. The Reproducibility Project’s large collaboration tried to replicate 100 psychology studies and found much weaker effects and far fewer statistically significant replications than the original literature suggested. (Science) Methodologists also showed how flexible analysis choices and reporting can inflate false positives unless stricter norms are enforced. (SAGE Journals) Meehl’s older critique still lands for the same reason: in “soft” areas of psychology, theories often fade away rather than being cleanly tested and retired. (Error Statistics Philosophy) The implication is not nihilism. It is epistemic humility, especially for claims that are politically charged and personally consequential.

Psychology’s history offers examples of ideas that persist on social momentum long after the evidence grows cloudy. The “memory wars” around repressed and recovered memories show how a compelling clinical narrative can endure in practice while mechanisms remain disputed, and how suggestion can complicate confident storytelling. (PMC) Lilienfeld and colleagues made the broader point in a different domain: weak measurement, loose constructs, and credulous clinical fashions predict confident claims that later demand painful correction. (Guilford Press) The pattern is simple: psychology is unusually prone to ideas becoming socially protected before they are empirically solid.

That is the right context for the strong activist version of “innate gender identity,” meaning the claim that very young children can reliably know and articulate a fixed inner gender that may mismatch their body, and that this knowledge should be treated as stable guidance for major decisions. Developmentally, this is exactly the kind of adult projection Piaget and Erikson warn against: treating children’s words as if they carry stable adult concepts while the child’s understanding and self-organization remain socially shaped and changeable. Even within clinical samples, trajectories are not uniform; intensity of childhood gender dysphoria is one known factor associated with persistence into adolescence, which is another way of saying early self-labels do not function like a universal diagnostic oracle. (PubMed) Clinically, the major classification systems are more cautious than the slogans: DSM-5-TR defines gender dysphoria around clinically significant distress or impairment, not the mere existence of an identity claim. (American Psychiatric Association) ICD-11 moved gender incongruence out of the mental disorders chapter and into “conditions related to sexual health,” partly to reduce stigma while preserving access to care. (World Health Organization)

The evidence environment around youth gender medicine shows why fad dynamics matter. The Cass Review argued the evidence base for medical interventions in minors is limited and often low certainty, urging caution and better research. (Utah Legislature) Substantial critiques dispute Cass’s methods and interpretation, which itself signals this is not a stable, high-consensus evidentiary domain. (PMC) The adult responsibility is therefore straightforward: treat childhood self-labels as developmentally real but conceptually limited; separate distress from metaphysics; demand the same evidentiary standards you would demand anywhere else in medicine; and resist turning a contested construct into a moral absolute. If psychology keeps rewarding certainty over rigor, the cost will not be merely bad theory. It will be policy and clinical practice that harden too early, then harm real people when the correction finally arrives.

Glossary

- Replication / reproducibility: Whether an independent team can rerun a study and obtain broadly similar results. (Science)

- Researcher degrees of freedom: The many choices researchers can make (when to stop collecting data, which outcomes to report, which analyses to run) that can unintentionally inflate “significant” findings. (SAGE Journals)

- P-hacking: Informal term for exploiting analytic flexibility to chase statistical significance. (SAGE Journals)

- Construct validity: Whether a measure actually captures the concept it claims to measure (not just something correlated with it). (General measurement concern emphasized in clinical-science critiques.) (Guilford Press)

- Gender dysphoria (DSM-5-TR): Clinically significant distress or impairment related to gender incongruence; not all gender-diverse people have dysphoria. (American Psychiatric Association)

- Gender incongruence (ICD-11): ICD-11 category placed under “conditions related to sexual health,” moved out of the mental disorders chapter. (World Health Organization)

- Persistence (in childhood GD research): Continued gender dysphoria into adolescence; research suggests persistence is not uniform, and intensity is one associated factor. (PubMed)

Short endnotes (audit-friendly)

- Replication crisis anchor: Open Science Collaboration (2015), Science; effects in replications notably smaller; fewer significant replications. (Science)

- Analytic flexibility / false positives: Simmons, Nelson & Simonsohn (2011), “False-Positive Psychology.” (SAGE Journals)

- Soft-psychology theory fade-out critique: Meehl (1978), “Theoretical Risks and Tabular Asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the Slow Progress of Soft Psychology.” (Error Statistics Philosophy)

- Memory wars as an example of contested clinical narratives: Otgaar et al. (2019, PMC) on repression controversy; Loftus (2006) review on recovered/false memories; Loftus (2004) in The Lancet on the continuing dispute. (PMC)

- Clinical-science warning about fads/pseudoscience: Lilienfeld et al., Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology (Guilford excerpts / volume). (Guilford Press)

- DSM-5-TR framing: APA overview and DSM-related materials emphasize distress/impairment as the diagnostic core. (American Psychiatric Association)

- ICD-11 move and rationale: WHO FAQ; supporting scholarly rationale for moving gender incongruence out of mental disorders while preserving access to care. (World Health Organization)

- Persistence factor (intensity): Steensma et al. (2013) follow-up: intensity of childhood GD associated with persistence. (PubMed)

- Cass Review debate: Cass Review final report PDF (archived copies); published critiques and responses indicating contested interpretation and ongoing debate. (Utah Legislature)

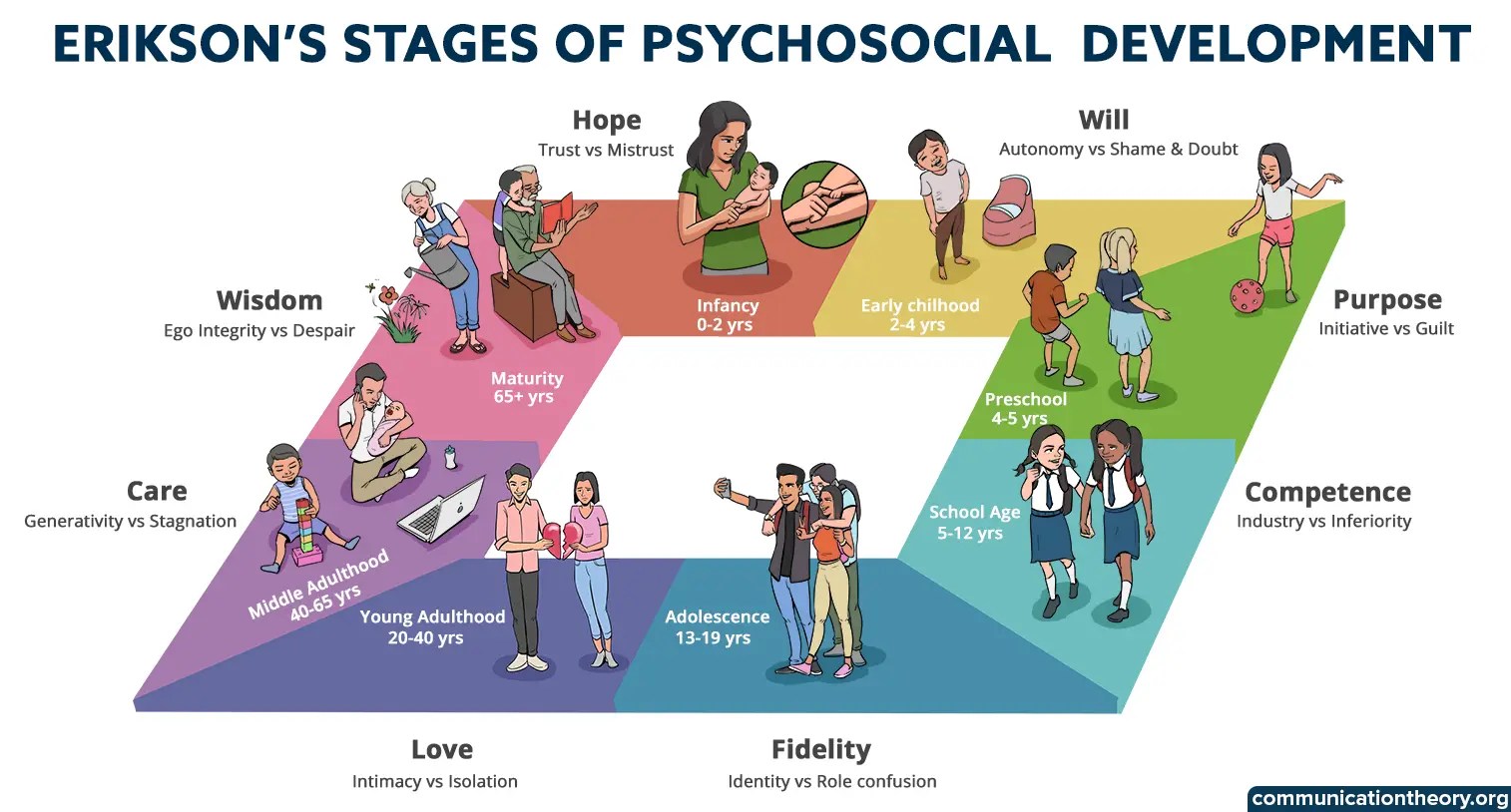

Erik Erikson is still useful because he blocks a modern temptation: reading a child’s self-descriptions as evidence of a finished, stable identity. For Erikson, identity is not an inner essence that appears early and then merely announces itself. It is something built across time under social conditions. Relationships, cultural scripts, permissions, limits, and feedback all shape what a person can plausibly become and what they can sustain. If you want a single takeaway, it is this: adults regularly project mature coherence onto children whose sense of “who I am” is still under construction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Erikson’s framework is psychosocial. He describes eight broad stages across the lifespan, each organized around a tension between two outcomes. The point is not a one-time pass or fail. It is a developmental task that tends to recur in new forms as life changes. When conditions are supportive, people lean toward the positive resolution and develop an associated strength or “virtue.” When conditions are hostile or mismatched, the negative pole can dominate and leave a durable vulnerability. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

In early childhood, the tasks are basic but not trivial. In infancy, trust versus mistrust is shaped by whether care is reliable and responsive. In toddlerhood, autonomy versus shame and doubt turns on whether a child can attempt self-control without being humiliated for mistakes. In the preschool years, initiative versus guilt turns on whether exploration and planning are welcomed or punished. These are not destiny. They are early patterns. They set default expectations about safety, agency, and permission that can be reinforced later or revised by later experience. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

School age brings industry versus inferiority. Children now meet the world of tasks, standards, and comparison. Competence grows when effort produces mastery and feedback is fair. Inferiority grows when failure is repeated, demands are mismatched, or judgment is harsh. This matters because it supplies the raw materials for adolescence. Identity versus role confusion is not about picking a label. It is about synthesizing roles, values, loyalties, and a changing body into something that feels continuous and workable. Researchers made this more testable by focusing on processes like exploration and commitment (roughly, trying roles out and then making durable choices), yielding familiar identity-status patterns such as diffusion, foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement. Longitudinal work also supports the commonsense point that identity development extends beyond the teen years for many people. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Erikson’s model deserves the criticisms it often receives. The stages function best as descriptive heuristics rather than strict schedules, and some concepts are hard to measure cleanly. The framework also reflects mid-20th-century Western assumptions, and feminist scholarship has pressed on its gendered blind spots. Still, the core insight survives: selfhood is social before it is philosophical. Children become “someone” through attachment, modeling, constraint, opportunity, and recognition. The practical reminder is blunt, feeding directly into today’s debates. Do not read adult-level identity stability into young children’s words or preferences. Much of what looks like certainty in a child is a snapshot of roles and reinforcement, not proof of a permanent inner core. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Glossary

- Psychosocial stage/task: A recurring developmental challenge shaped by social context, not a biological timer. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Virtue (Erikson): A strength associated with a relatively positive resolution of a stage task (e.g., hope, will, competence, fidelity). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity vs role confusion: The adolescent task of developing a workable sense of continuity across roles, values, and future direction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity statuses (Marcia tradition): A research approach using exploration and commitment to classify patterns like diffusion (low both), foreclosure (commitment without exploration), moratorium (exploration without commitment), and achievement (exploration leading to commitment). (Wikipedia)

Endnotes

- Erikson stages overview, virtues, and the “not pass/fail” framing: StatPearls (Orenstein, 2022). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Scholarly overview and modern framing of Erikson as a lifespan theory: Syed & McLean (2017, PsyArXiv).

- Identity-status trajectories and measurement of exploration/commitment over time: Meeus (2011, PMC). (Wikipedia)

- Marcia identity-status grounding in Eriksonian identity crisis: foundational identity-status paper (PDF record).

- Feminist critique and gender-bias discussion of Eriksonian identity: Sorell (2001).

A classically liberal society survives on habits, not slogans. It needs restraint, due process, toleration, and the willingness to lose without declaring the system illegitimate. Those habits are the machinery that lets disagreement stay political instead of becoming civil war by other means.

Here is the problem: liberalism can be weakened without censorship or coups. You dissolve it by corroding its reflexes. Make truth optional. Make process contemptible. Make opponents morally untouchable. Then the only “honest” politics left is permanent emergency.

Toolkits like Beautiful Trouble matter because they don’t merely argue for outcomes. They teach a style of conflict that can push a society toward that emergency posture. Not secretly. Openly. Proudly.

The mechanism: reaction as leverage

The core move is simple: the decisive moment is not what you do; it is how the target reacts. Beautiful Trouble states this as principle. Create a situation where the target has only bad options. If the target responds forcefully, you get optics of oppression. If the target hesitates, you get optics of weakness or complicity. Either way, you harvest narrative.

This is not foreign to the Alinsky lineage. The organizing sensibility there is similarly pressure-driven: personalize, polarize, keep heat on, force choices. Whether you call that “empowering the powerless” or “cynical theatre” depends on your politics. But the effect is measurable. It rewards escalation.

In an attention economy, that reward multiplies. The clip travels. The caption hardens. The audience concludes. Process arrives too late to matter.

Why this is corrosive to liberal life

Classical liberalism is not blind to power. It assumes power exists and will be abused. That’s why it builds constraints: rule of law, rights, neutral adjudication, stable procedures, and a civic ethic that treats opponents as citizens.

Revolutionary politics often treats those constraints as camouflage for domination. Once you accept that premise, liberal restraint stops being virtue and becomes collaboration. Due process becomes “violence.” Neutrality becomes “support for the status quo.” Compromise becomes betrayal.

That frame is solvent. It dissolves the very institutions that make peaceful reform possible. Courts become illegitimate. Journalism becomes propaganda. Elections become theatre. At that point, direct action isn’t one tool among many. It becomes the only “authentic” politics. And authenticity is a poor substitute for governance.

Three tactics that act like acid

1) Identity tricks that blur truth and theatre

Impersonation formats, spoof announcements, and “identity correction” are often defended as satire. Sometimes they are. But they also train a destructive habit: truth is what produces the right reaction.

In a low-trust society, that habit is gasoline. It makes people easier to steer. They learn to treat moral satisfaction as verification.

2) Reaction capture that rewards escalation

Media-jacking and engineered dilemmas push institutions into visible confrontation. Institutions then over-respond to avoid losing control. Activists then present the response as the point. The public is invited to judge the system from the most inflammatory ten seconds.

This is why incremental reform struggles. Incrementalism is procedural. It is slow. It is boring. It does not produce good clips. When politics is mediated by clips, boredom becomes political death. And the responsible becomes invisible.

3) Framing that turns disagreement into moral emergency

The most dangerous tool is not a hoax. It is framing that converts disagreement into existential crisis. Once politics is narrated as emergency, restraint becomes treason. Any compromise becomes proof of corruption. The only acceptable posture becomes maximal conflict.

That is how a society stops being governable. Not because people disagree, but because they can no longer share a procedure for disagreement.

The case for incremental progress

Incrementalism is mocked as cowardice. It is not. It is the political expression of two hard truths.

First, institutions are complex. Sudden shocks break things you cannot rebuild at will. Second, moral certainty is a poor engineer. It is good at burning. It is bad at designing.

Classical liberal reform says: specify the harm, propose bounded remedies, build coalitions, accept partial wins, and keep the legitimacy of procedure intact. That is not complacency. It is the recognition that power vacuums don’t stay empty, and that revolutions rarely end with stable liberty.

If you care about justice, you should fear the emergency habit. Emergency is where rights go to die. Emergency is where “temporary” powers become permanent. Emergency is where the loudest faction learns it can rule by accusation.

A prediction worth taking seriously

As these tactics normalize, politics will become less about persuasion and more about provocation. Institutions will either harden into managerial coercion or retreat into paralysis. Both outcomes invite more radicalism, because both outcomes confirm the radical story.

A liberal society that wants to survive has to stop rewarding engineered crisis. That means demanding evidence over captions, procedure over theatre, and reform over revolution, even when reform is unsatisfying. Especially then.

References

-

Beautiful Trouble toolbox and principle page (reaction as leverage).

Beautiful Trouble tactic pages: Identity correction; Media-jacking.

OR Books listing / bibliographic info for Beautiful Trouble editions.

Secondary summaries of Rules for Radicals (Alinsky overview used for comparison of tactical sensibility).

Beautiful Trouble is a public toolbox for creative activism: first a collaboratively assembled book, later an online repository, and now also a training ecosystem. Its pitch is not subtle. Movements don’t only need convictions; they need methods.

The core value of Beautiful Trouble is not that it “proves” anything about the morality of activism. The value is that it exposes a modern fact of politics: attention is terrain. If you want to understand contemporary protest, you have to understand how actions are designed to travel, how institutions are pushed into visible choices, and how audiences form conclusions with partial information.

The project’s structure supports that aim. It’s modular: tactics, principles, theories, and short case stories that can be mixed and reused. It describes itself as a kind of “pattern language,” and its licensing encourages adaptation. That makes it unusually legible as an object of civic study: it doesn’t hide the playbook.

What it optimizes for

Most people still think politics is mainly argument. It isn’t. Not anymore. It’s increasingly interpretation under time pressure.

A large share of the public will never read the policy memo, the injunction, or the investigative timeline. They will see a clip. They will inherit a caption. They will absorb a moral frame already installed. Beautiful Trouble is built for that environment. It treats activism as attention design: actions shaped to be seen, remembered, and shared.

One of its principles says the quiet part out loud: the decisive moment is often the target’s response. That is not inherently nefarious. It is a standard logic in asymmetric conflict. When you can’t move power directly, you provoke power into showing itself.

For media literacy, this yields a simple rule: some public actions are designed less to “state a grievance” than to produce a reaction that will be more persuasive than the grievance.

Three clusters worth understanding

The toolbox contains many tools, but three clusters matter for public comprehension because they recur across movements and because they interact strongly with journalism and social media.

1) Impersonation formats and “identity correction”

The toolbox includes tactics associated with hoaxes, spoof announcements, and “identity correction.” These actions usually aim to create a dilemma: if the target rejects the message, the target may look callous; if it accepts any part of it, the target concedes ground. Their success depends on speed. A claim that travels faster than verification can leave residue even after correction.

The neutral point is not “this is always unethical” or “this is always justified.” The point is functional: these tactics exploit a predictable weakness in information flow. Novelty beats confirmation. Moral satisfaction beats caution.

The reader’s defense is boring and effective: treat “too perfect” claims and “official-sounding” announcements as unverified until corroborated.

2) Media-jacking and reaction capture

Another cluster focuses on borrowing attention: hijacking an event, inserting into an opponent’s stage, or redirecting a news cycle. The target is forced into a choice: ignore the action and risk looking weak or indifferent; respond forcefully and risk producing the exact optics the activists want.

This is why the response becomes the payload. The goal is often to make the institution appear brittle, panicked, or oppressive, whether through its own errors or through selective presentation.

The media-literacy question here is straightforward: is the target reacting to a genuine threat, or to an engineered dilemma designed to force a visible response? Sometimes it’s both. Don’t let a viral clip collapse the distinction.

3) Framing and reframing as the main contest

The most consequential “tactic” is not a stunt. It is framing: assigning roles, values, and categories before evidence arrives. What counts as “violence”? What counts as “self-defense”? What counts as “harm”? What is “legitimate”?

Framing is unavoidable. Humans need categories. But because it is unavoidable, it can be weaponized. When framing succeeds, neutral description becomes socially costly. Even vocabulary starts to signal affiliation.

The most reliable defense is category discipline. Separate:

-

what happened (event),

-

what the rule was (policy),

-

what the law allows (legal),

-

what you think is right (moral),

-

what will work (strategic).

Framing tries to weld those together into one reflex. Citizens stay free by refusing that weld.

What this means for civic competence

Beautiful Trouble is a public, teachable catalog of activist methods. That is precisely why it matters. It’s a window into how modern movements think about leverage in an attention economy.

The neutral takeaway is not “activism is manipulation.” It is that contemporary politics runs on reaction, narrative compression, and low-context consumption. A public that wants to be hard to steer needs one habit: slow the tape when an event arrives already framed as a moral emergency.

That is media literacy now. Not cynicism. Pattern recognition. 🧠

References

-

Beautiful Trouble homepage / toolbox landing pages.

Beautiful Trouble principle page (“the real action is your target’s reaction”).

Beautiful Trouble tactic pages: Identity correction; Media-jacking.

-

OR Books listing for Beautiful Trouble: Pocket Edition.

-

ICNC resource entry describing Beautiful Trouble as book/toolbox/training resource.

-

Google Books bibliographic page for Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution.

In his January 16, 2026 X post, James Lindsay treats the “ICE is Trump’s Gestapo” line as more than overheated language. He reads it as a political technique: a framing move that aims to provoke escalation, polarize interpretation, and sap legitimacy from federal immigration enforcement by making every subsequent clash look like retroactive confirmation.

Even if you don’t accept the strongest version of his claim (that it is centrally orchestrated), the underlying mechanism is worth taking seriously—because it doesn’t require orchestration to work. It requires an audience that consumes politics in fragments, and a media ecosystem that pays for heat.

The point of media literacy here is not to pick a side. It is to recognize when you are being handed a frame that’s designed to steer your moral conclusion before you are allowed to know what happened.

The loop, reduced to mechanics

The escalation loop has four moves.

1) Load the moral frame early.

“Gestapo” is not an argument. It is a verdict. It tells the audience what they are seeing before they see it. It collapses a contested enforcement dispute into a single image: secret police.

2) Convert observation into resistance.

Once people believe they’re facing secret police, ordinary scrutiny becomes morally charged. Disruption can be reframed as defense. Escalatory behavior becomes easier to justify, especially in crowds, especially on camera.

3) Force a response that looks like the frame.

As tension rises, agents harden posture: more crowd-control readiness, more force protection, more aggressive containment. Some of that may be lawful, and some may be excessive; the loop does not depend on the fine print. It depends on optics.

4) Circulate optics as proof.

Clips win. Captions win. The most provocative 15 seconds becomes “what happened,” for millions who will never read a court filing. The frame spreads because the frame is legible in low context.

Frame → friction → hardened posture → optics → reinforced frame. Repeat.

Notice what’s missing: slow adjudication of facts. The loop thrives on speed. It preys on low-context attention.

Why Minnesota is an instructive case

Minnesota matters here because the escalation loop is visible across multiple lanes at once: street-level conflict, political rhetoric, and rapid legal constraint.

Recent reporting describes the Department of Homeland Security deploying nearly 3,000 immigration agents into the Minneapolis–St. Paul area amid intense protests and public backlash. In that environment, a fatal shooting—Renée Good, shot by an ICE agent on January 7, 2026—became a catalytic event for further demonstrations and scrutiny.

Then the conflict moved into procedural warfare. On January 17, a federal judge issued an injunction restricting immigration agents from detaining or using force (including tear gas or pepper spray) against peaceful protesters and observers absent reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. That order is narrow, but it is not trivial: it codifies a boundary in exactly the arena where optics are most easily weaponized.

The rhetorical layer matters too. DHS has publicly condemned Minnesota Governor Tim Walz for using “modern-day Gestapo” language about ICE (and the White House has amplified that criticism). Whatever you think of the underlying enforcement operation, this is the accelerant: the label that turns complexity into a single moral picture.

If you want a single media-literacy takeaway from Minnesota, it’s this: the escalation loop often ends up constraining policy through courts and procedure, not merely through street confrontation. Once the story becomes “secret police,” legal process itself becomes part of the narrative battlefield—injunctions and motions become content, and content becomes legitimacy.

“Low information public” is the wrong diagnosis

“Low information” is typically used as a sneer. The sharper term is low context.

Most people aren’t stupid; they’re busy. They consume politics the way they consume weather: by glance. They get fragments, and fragments invite frames.

The “Gestapo” label works on low-context audiences because it is:

- Instantly moralized: villain and victim are assigned immediately.

- Highly visual: it primes the brain to interpret normal enforcement cues (gear, urgency, crowd control) as secret-police signals.

- Clip-native: it fits perfectly into captions and short video, where emotional clarity beats evidentiary completeness.

- Correction-resistant: anyone who says “slow down” can be painted as defending tyranny.

This is the real vulnerability narrative warfare exploits: not ignorance, but context starvation.

The key analytical distinction: intent vs incentives

Here’s where writers often lose credibility: they jump from “this pattern exists” to “this was orchestrated.”

Sometimes there is coordination. Often there isn’t. And you typically don’t need it to explain outcomes.

Shared incentives can produce coordinated-looking behavior without a central planner:

- Outrage frames mobilize attention.

- Attention produces fundraising, followers, and headlines.

- Headlines pressure officials and constrain institutions.

- Institutions respond in ways that produce more outrage footage.

That is enough.

The media action depends on showing a self-reinforcing system: rhetoric that increases confrontation risk, confrontation that increases hardened posture, posture that increases “secret police” plausibility to spectators.

That is media literacy: the ability to separate “this felt true on my feed” from “this is true in the world.”

How to defuse the loop

Defusing the escalation loop means starving it of inputs. That requires two fronts: institutional discipline and citizen discipline.

What institutions can do

1) Treat optics as a real constraint (not PR garnish).

In a clip-driven environment, unnecessary spectacle is narrative fuel. If tactics can be lawful and less visually coercive, the second option is often the strategically sane one.

2) Over-communicate rules, thresholds, and remedies.

Explain what triggers stops, detentions, and uses of force; explain complaint pathways; publish policy boundaries. If courts are drawing bright lines around peaceful protest and observation, those lines should become part of the public-facing doctrine, not buried in litigation.

3) Correct fast and publicly when mistakes occur.

Silence functions as permission for the loudest interpretation to win. Delay is a gift to the escalation loop.

4) Avoid “timing that reads like punishment.”

Even lawful actions can look retaliatory if they cluster around protests. In narrative warfare, timing becomes motive in the audience’s mind.

What readers can do

1) Treat moral super-labels as a stop sign.

When you see “Gestapo,” “fascist,” “terrorist,” “insurrection,” assume you’re being pushed into a conclusion. Slow down.

2) Refuse clip capture.

Ask: what happened thirty seconds before this clip starts? If you can’t answer, you’re watching a weaponized excerpt.

3) Use a two-source minimum.

One source gives you mood. A second source often provides the missing constraint—timeline, legal posture, or what is actually being alleged. The injunction’s specific limits, for example, are precisely the kind of detail clips rarely include.

4) Separate event, legality, and morality.

“This happened” is not “this was lawful,” and neither is “this was tyranny.” Narrative warfare succeeds by collapsing those categories into one reflex.

5) Ask what behavior the story is trying to elicit.

Is it trying to make you understand, or to make you react—share, donate, show up, escalate? That question alone breaks many spells.

Where this ends if we don’t learn

If the escalation loop runs unchecked, politics becomes performance for low-context consumption. Enforcement becomes optics. Protest becomes optics. Courts become props. Everyone plays to the camera because legitimacy is increasingly adjudicated there.

The antidote isn’t bland neutrality. It’s refusing to let a frame do your thinking for you—especially one engineered to convert fragments into certainty.

That’s what media literacy looks like now: not knowing everything, but knowing when you’re being steered.

“When a word arrives preloaded with a verdict, your job is to slow the tape.”

References

- James Lindsay, X post (January 16, 2026), “ICE is Trump’s Gestapo” narrative thread. (X (formerly Twitter))

- Reuters (January 17, 2026), report on federal judge’s injunction limiting immigration agents’ tactics toward peaceful protesters/observers in Minneapolis–St. Paul; includes mention of DHS deploying nearly 3,000 agents and context following Renée Good’s death. (Reuters)

- Associated Press (January 17, 2026), coverage of the same injunction and the lawsuit context, including limits on detentions and crowd-control measures against peaceful protesters/observers. (AP News)

- ABC News (January 14, 2026), background reporting confirming Renée Good was fatally shot by an ICE agent on January 7, 2026 and noting an FBI probe. (ABC News)

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security (May 19, 2025), DHS statement criticizing Gov. Tim Walz’s “modern-day Gestapo” language about ICE (useful for documenting the rhetoric’s public circulation). (Department of Homeland Security)

- White House (January 2026), article compiling public statements about ICE and “modern-day Gestapo” language (useful as an example of administration amplification rather than a neutral factual source). (whitehouse.gov)

Your opinions…