You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Philosophy’ category.

When political violence erupts, it often looks random — a lone extremist, a protest that gets out of hand, or a clash between two angry groups. But much of what we’re seeing today, in both the United States and Canada, is not random at all. It is part of a deliberate strategy that activists call dialectical warfare — and it is tearing at the heart of our democratic societies.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk and the furious conservative backlash that followed are not isolated events. They are part of a larger spiral of violence and reaction, one that radicals hope will end with the collapse of our current system. To understand how, we need to unpack an old idea: the dialectic.

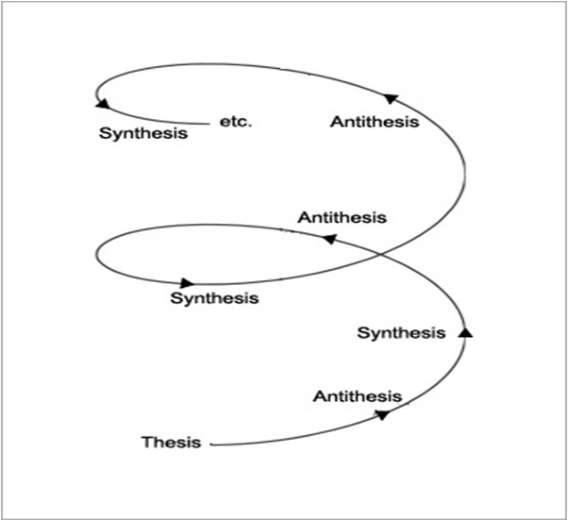

What is the Dialectic?

The word “dialectic” comes from philosophy, specifically the German thinker Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in the early 1800s. At its simplest, the dialectic is a way of describing how history moves forward through conflict.

- Thesis: the current system or status quo.

- Antithesis: the force that challenges it.

- Synthesis: a new system that emerges after the clash.

For Hegel, this was a way of understanding history as a story of progress. Marx later took this idea and made it the foundation of his revolutionary theory. For him, history was about class struggle: workers against capitalists. Capitalism, he argued, would eventually collapse under its contradictions and give way to communism.

The key point is this: conflict isn’t a bug in the system — it’s the engine of history.

From Philosophy to Political Activism

Fast forward to today. Many left-wing activists, consciously or not, operate with a dialectical mindset. They believe that society advances through conflict and breakdown, not peaceful debate.

That means chaos, division, and even violence can be seen as useful. If enough conflict is stirred up, the system will be forced to reveal its flaws, overreact, and eventually collapse — clearing the way for something new.

This isn’t conspiracy theory. Activist manuals, writings from radical groups, and historical revolutionary movements all share this logic. The goal is not stability. The goal is destabilization.

Dialectical Warfare Today

Dialectical warfare is what happens when activists deliberately create or amplify conflict to destabilize society. Here’s how it works in practice:

- Provocation: Protests or acts of violence designed to draw a harsh reaction.

- Overreaction: Authorities or opponents respond too aggressively, confirming the activists’ narrative.

- Crisis: The clash erodes faith in institutions and convinces people the system doesn’t work.

- Escalation: Each cycle of conflict moves society further up the spiral toward collapse.

It’s not about winning the argument. It’s about breaking the system so that something “better” (usually some form of socialist utopia) can be built on the ruins.

The Charlie Kirk Case

The recent assassination of Charlie Kirk shows this dynamic clearly. For the radical Left, the act of violence itself was a shock designed to destabilize. But what mattered more was the reaction.

Conservatives in power, outraged and furious, began employing the same tools that had once been used against them: censorship, cancel culture, and efforts to silence left-wing voices. In their anger, they began shredding the same democratic norms — free speech, due process, respect for law — that they had once fought to defend.

From the perspective of dialectical warfare, this is a victory for the radicals. The point was never just to kill one man. The point was to provoke an overreaction that would weaken the credibility of conservative leaders, make democratic institutions look fragile, and drive polarization even deeper.

Why This is Dangerous

Every time conservatives react by copying the authoritarian tactics of the Left, they confirm the radicals’ worldview. They prove that democracy is a sham, that free speech is a lie, and that the system is doomed.

This is exactly what the activist Left wants. They welcome conservative overreach, because it accelerates the collapse of the old order. The tragedy is that in fighting back, the right risks becoming what it hates: reactionary, authoritarian, and destructive of the very freedoms it claims to defend.

Lessons from History

We have seen this before. In the 20th century, totalitarian movements from Communism in Russia to fascism in Germany thrived on dialectical conflict. They used street violence, political assassinations, and manufactured crises to polarize society. Each overreaction by their opponents brought them closer to power.

The idea is seductive: “This system is broken. Only radical action can save us.” But the results are always catastrophic. Millions died under regimes that promised utopia and delivered tyranny.

A Simple Analogy

Think of democracy like a family car. It’s not perfect — sometimes it breaks down, sometimes it needs repairs. Activists practicing dialectical warfare are not trying to fix the car. They are trying to crash it on purpose, believing that after the wreck, they’ll be able to build a perfect new vehicle.

But history shows that after the crash, what you usually get is not a better car — it’s a dictatorship.

The Dialectical Spiral at Work

To make this crystal clear, here’s how activists see the spiral — and what really happens:

| Stage | Activist Left’s View | What Actually Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Provocation | Stir conflict (riots, violence, incendiary rhetoric) to expose “systemic oppression.” | Communities destabilize; trust erodes. |

| Reaction | Force conservatives into authoritarian overreach. | Free speech and rule of law weaken; institutions lose credibility. |

| Crisis | Show that democracy and capitalism can’t solve the conflict. | Cynicism deepens; polarization hardens. |

| Escalation | Push society up the spiral toward “revolution and utopia.” | Cycle repeats, leading not to utopia but greater instability. |

Why We Must Resist

The activists’ dream of a communist utopia is a fantasy that has failed every time it’s been tried. But their strategy of dialectical warfare is very real — and very effective at breaking societies apart.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk and the conservative overreaction it triggered are a warning. If we allow ourselves to be baited into authoritarian responses, we are not saving democracy — we are digging its grave.

The only way forward is to resist the spiral: to defend free speech, uphold the rule of law, and refuse to play into the radicals’ hands. Otherwise, we will all be dragged into the chaos they long for, and the freedoms that make Western society unique will vanish in the wreckage.

References

- Hegel, G.W.F. The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807).

- Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Communist Manifesto (1848).

- Arendt, H. On Violence (1970).

- Popper, K. The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945).

- Contemporary coverage: Reuters, Associated Press, Fox News (Sept. 2025) – reporting on the assassination of Charlie Kirk and ensuing political fallout.

An Impasse in Discourse

We’ve all encountered it: a conversation where the goal isn’t mutual understanding but moral one-upmanship. You offer a reasoned point—say, that judging people by character over skin color fosters unity—and instead of engagement, you’re met with a lecture on your “ignorance.” This isn’t dialogue; it’s a sermon.

Such exchanges, common among adherents of what’s loosely called “woke” ideology, reveal a deeper issue: an unshakable belief in possessing the final truth. Why does this happen? I propose it stems from a process called consciousness raising, which breeds an ideological certainty akin to ancient gnosticism—a conviction that one’s insight is not just superior but unassailable.

Defining “Woke” and Its Roots

By “woke,” I mean specific ideological strands—critical race theory, certain forms of identity politics, and intersectional activism—that frame society as a rigid hierarchy of oppressors and oppressed, with truth grounded in lived experience over empirical evidence. This isn’t a blanket condemnation of social justice; many concerns, such as disparities in criminal justice, are real and urgent. But the approach often corrodes open debate by replacing inquiry with moral accusation.

Consciousness raising, rooted in second-wave feminism and Marxist praxis, promises a “critical reorientation” of reality (MacKinnon, 1983). Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s concept of conscientização urged the oppressed to awaken to the forces of their subjugation (Freire, 1970). Today, this manifests in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) trainings, where participants are guided to “see” systemic power structures—often without room for dissent, questions, or reciprocal inquiry.

The Sociognostic Mindset

This form of ideological certainty resembles gnosticism, the ancient belief in salvation through secret knowledge. While woke ideology is hardly esoteric—its claims are publicly championed—it shares a similar epistemic posture: what we might call sociognostic certainty. This is the conviction that one’s moral and political views reflect a deeper awareness of systemic oppression, an awareness that cannot be achieved through conventional reasoning alone.

Think of it as moral X-ray vision: the ability to detect the systemic injustices that the unenlightened cannot see. Those who haven’t undergone this awakening—those who do not “get it”—aren’t just wrong; they’re unconscious. As Ibram X. Kendi puts it, “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination” (Kendi, 2019). To disagree is not to reason differently—it is to expose your ignorance.

This mindset doesn’t just shape what the Woke believe—it shapes how they interact with others who haven’t reached the same “insight.” The consequence is a failure of dialogue.

Why Debate Fails

Consider a fraught topic like racism. An honest interlocutor might argue for a color-blind approach: judge individuals by their actions, not immutable traits. To the sociognostic mind, this is not merely naïve—it is harmful. They insist that racism permeates every facet of society—systemic, structural, inescapable. Even color-blindness, they argue, is a form of complicity—a refusal to acknowledge the depth of the problem (DiAngelo, 2018).

The issue isn’t the argument’s logic; it’s the knowledge differential. The Woke interlocutor, armed with raised consciousness, believes they occupy a higher moral plane. Dissenters, lacking this insight, are not engaged—they are dismissed. And not with counterarguments, but with labels: racist, bigot, transphobe. These are not rebuttals. They are excommunications, designed to enforce a moral hierarchy where only the awakened may speak with authority.

Engaging the Counterargument

Proponents of this mindset argue that systemic issues—like racial disparities in wealth or incarceration—require a radical lens. They would say critiques like this one ignore how power shapes social reality in ways that the privileged cannot see. It’s a fair point: history isn’t neutral. Data show that Black Americans, for instance, are incarcerated at nearly five times the rate of whites (NAACP, 2023).

But I would argue that the sociognostic approach often fuels division rather than solutions. By prioritizing ideological purity over shared reasoning, it alienates potential allies and entrenches resentment. Research from the National Institute of Justice (2021) suggests that economic opportunity, community trust, and procedural fairness reduce disparities more effectively than moral posturing. While the woke framework highlights real problems, it risks replacing deliberation with dogma.

Navigating the Impasse

Empirical arguments won’t suffice when beliefs rest on moral certitude rather than falsifiable evidence. You may find yourself dismissed—your reasoning reduced to “privilege” or “fragility”—not because you’re wrong, but because you’re presumed unawakened. As Pluckrose & Lindsay (2020) explain, applied postmodernism prioritizes subjective identity over objective reasoning. You’re not in a debate—you’re interrupting a sermon.

The key is to remain grounded. Ask questions. Demand evidence. Refuse to be shamed into silence. Clarity and patience—not moral posturing—are your best tools.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Shared Ground

The frustration of arguing with woke ideology isn’t just cultural—it’s epistemological. Its sociognostic posture assumes a monopoly on moral truth, turning discourse into a hierarchy of insight rather than a collaborative pursuit of understanding. That is corrosive to unity, which depends on open exchange, mutual respect, and rational inquiry.

We must resist this tendency—not with venom, but with commitment: to shared reason, to factual evidence, and to the possibility that even the loudest moral certainty can be wrong. The alternative is a world where sermons replace arguments. And that’s a debacle we can’t afford.

References

- DiAngelo, R. (2018). White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press. Link

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum. Archive

- Kendi, I.X. (2019). How to Be an Antiracist. One World. Link

- MacKinnon, C.A. (1983). “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: An Agenda for Theory.” Signs, Vol. 7, No. 3. JSTOR

- NAACP. (2023). “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” NAACP.org

- National Institute of Justice. (2021). “Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Justice System.” NIJ.gov

- Pluckrose, H., & Lindsay, J. (2020). Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity. Pitchstone Publishing. Link

- No one has the last say on anything (the principle of open-ended inquiry, where no authority can definitively settle a matter, and all claims are subject to challenge and revision).

- No one gets to say who gets to speak (the principle of equal access to the marketplace of ideas, where everyone has the right to express their views without being silenced by authority).

When assessing an argument or movement, ask: Does it uphold these principles? For example, does a critique seek to shut down debate by declaring certain ideas off-limits, or does it invite open challenge? Does it exclude voices based on ideology, or does it allow all perspectives to compete in the marketplace of ideas? If the answer is no to either question, the argument may be more about unraveling the fabric of liberal society than improving it.

- Publisher’s Website: The University of Chicago Press, which publishes the expanded edition (2013), provides details and purchasing options: University of Chicago Press – Kindly Inquisitors.

- Amazon: Available in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook formats: Amazon – Kindly Inquisitors.

Immanuel Kant’s Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (1783) isn’t a dusty academic exercise—it’s a philosophical thunderbolt, forged in a crisis of certainty. In the late 18th century, the Enlightenment’s worship of reason was faltering, and Kant, a Prussian thinker with a mind like a steel trap, stepped in to redefine how we know reality. His work wasn’t just a rebuttal to skeptics like David Hume; it was a radical reimagining of reality itself, as something our minds actively shape. To understand what Kant brought to the table, we must dive into the “when” and “why” of his revolution, where battles over facts, morals, and truth set the stage for his seismic ideas.

The Historical Context: A Philosophical Crisis

The 1700s were a crucible for ideas. Enlightenment giants like Newton mapped the physical world, but philosophy was in turmoil. Rationalists like Leibniz spun grand theories about reality’s essence—God, the soul, universal laws—claiming reason alone could crack them open. Then came David Hume, whose 1739 Treatise of Human Nature tore through these systems like a wrecking ball. Hume argued that causality wasn’t a law carved in reality’s bones but a habit of mind: we see a ball roll after a push and assume cause and effect, but it’s just expectation, not truth. Worse, in his infamous “is/ought” problem, Hume exposed a fatal gap in moral reasoning: no fact (“is,” like “people keep promises”) logically justifies a moral duty (“ought,” like “you should keep promises”). Morality, he suggested, was rooted in feelings, not reason—a devastating blow. If causality and morality were mere habits, metaphysics, the quest to know reality’s nature, was teetering on collapse.

Kant, jolted awake by Hume’s skepticism (Prolegomena, Preface), saw the stakes: without a firm foundation, metaphysics was doomed to dogma or doubt. His Prolegomena was a lifeline, aiming to make metaphysics a science by rethinking how we know reality—and morality—through reason’s lens, not just observation’s haze.

Kant’s Big Idea: The Copernican Turn

Kant’s response was a philosophical upheaval, his “Copernican revolution.” Like Copernicus placing the sun at the cosmos’ center, Kant argued our minds don’t just receive reality—they shape it (Prolegomena §14). Reality splits into two realms: phenomena (things as they appear, molded by our mind’s tools like space, time, and causality) and noumena (things-in-themselves, unknowable raw reality). Imagine a sunset: you see colors and shapes, a phenomenon crafted by your mind’s framework, not the sun’s ultimate essence (noumenon). For Hume’s “is/ought” problem, Kant’s answer is subtle but profound: facts (“is”) belong to phenomena, but moral “oughts” stem from reason’s universal laws, hinting at the noumenal realm of free will. For example, “people lie to gain advantage” (is) doesn’t justify “you shouldn’t lie” (ought)—but reason’s demand for universal consistency does, as Kant later argues in his moral works.

Why It Mattered Then—and Now

Kant’s framework saved metaphysics from Hume’s wrecking ball. He showed that truths like “every event has a cause” or moral duties like “don’t lie” aren’t just habits but necessary rules our minds impose (Prolegomena §18). Against rationalist overreach, he set limits: we can’t know noumena like God or the soul’s essence. This balance—rigor without hubris—electrified 1780s Europe, sparking debates in Prussian salons. Today, Kant’s ideas echo in questions about AI or virtual reality: if our minds shape phenomena, what’s “real” in a digital world? His framework challenges us to see reality as a story we co-author, not just a fact we uncover.

The Takeaway

Kant didn’t just patch metaphysics; he rebuilt it. By showing how our minds shape reality—facts and morals alike—he gave us tools to navigate truth with certainty while admitting our limits. The Prolegomena is his battle cry, born from Hume’s challenge to reason’s reach. Next time you wrestle with what’s “real” or “right,” remember Kant: your mind isn’t just seeing the world—it’s writing its rules.

Philosophy Professor Letitia Meynell in this portion of an essay postulates how we need to deal with ‘woke’ in our society. I read the essay and found that it misses one of the key aspects of ‘woke’ and that is the use of polysemy to confuse the meanings of words and terms. Let’s read her essay together and then propose a some counters to her arguments. A long read, but it is necessary to see how ‘woke’ works in the wild and what you can do to counter it.

“A few years ago, there was considerable anxiety in some quarters about “political correctness,” particularly at universities. Now it’s known as wokeness, and even though the terminology has changed, the concerns are much the same.

Some years ago, I offered an analysis of political correctness that equally pertains to wokeness today. What interests me are ways to think about and discuss political correctness/wokeness so as to avoid polarizing polemics and increase mutual understanding.

The goal is to help us all envision and create a more just and peaceful society by talking with each other rather than talking past each other.

‘Woke interventions’

Typically, “wokeness” and “woke ideology” are terms of abuse, used against a variety of practices that, despite their diversity, have a similar character. Often, what is dismissed as “woke” is a new practice that is recommended, requested, enacted or enforced as a replacement for an old one.

These practices range from changing the names of streets, institutions and buildings to determining who reads to pre-school children in libraries and altering the words we use in polite conversation.

When a practice is identified as “woke,” there is an implication that the non-woke practice is better or at least equally good. Thus the dismissal of something as “woke” is an endorsement of some alternative.

If we stop there, all we will see is a power struggle between progressive and conservative values. To dig deeper, I am going to share a particular case of calling out, or language policing, as an example of wokeness.

This incident happened to a Jewish friend of mine when we were students. She was directing a play about the Holocaust and, during auditions, a young woman casually used the word “Jew” to mean cheat. When my friend challenged this, the young woman asserted that it wasn’t offensive; it was just the way people from her town talked.

In the wrong

I use this example because I think it’s clear this young woman was in the wrong. My friend wasn’t being overly sensitive and was right to call her out.

But this example is also useful because it’s fairly typical of cases where someone attempts a “woke intervention” and it’s rejected — someone follows a practice that is common in their community, a “woke” intervenor calls it out, and the person responds not with an apology or even a question, but with outright dismissal.

Often, such responses come with an explicit criticism that the “woke” intervenor is over-sensitive, irrational or controlling. Sometimes, the original speaker claims victimization at being targeted, ironically displaying the hypersensitivity often attributed to people described as woke.

Three claims

In thinking about this and similar situations, it strikes me that woke interventions tend to share the same kinds of motivations. They boil down to the following three claims about the targeted practice that justify the woke intervention:

- The practice is offensive to the members of a group to which it pertains;

- The practice implies something that is false about this group and reflects and reinforces this inaccuracy;

- The practice implicitly endorses or maintains unjust or otherwise pernicious attitudes about the group that facilitate discrimination and various other harms against them.

So, in my friend’s case, she was right to call out this young woman, who had insulted her to her face and implied something about the Jewish community that is not only false but dangerously and perniciously antisemitic.

Now, in any particular instance, it is an open question whether, in fact, a specific term or practice is offensive, inaccurate or facilitates discrimination. This is where the difficult work starts.

Real effort is required to learn to see injustices that are embedded in our ordinary language and everyday practices.

Social psychological work on implicit biases suggests that good intentions and heartfelt commitments are not enough. It takes integrity and courage to critically examine our own behaviour and engage in honest conversations with people who claim we have hurt them.

However, once we recognize what’s at stake, to dismiss something as woke is a refusal to even consider the possibility that the targeted practice might be offensive, premised on false or inaccurate claims or discriminatory or harmful.

Defensiveness

Often such refusals are grounded in defensiveness and embarrassment. I suspect many of us can recognize the young woman’s sense of shock, hurt and denial at being called out for her behaviour.

But for those who disagree with a woke intervention, the right response is not glib dismissal or bombastic accusations of “being cancelled.”

Rather — after a sincere attempt to understand the woke intervenor’s perspective and consider the relevant facts — the right response is a respectful, tempered explanation of why they believe their remarks or actions were neither premised on false claims nor discriminatory. An apology may be in order. After all, at the very least, one has inadvertently insulted someone.

If my analysis is correct, we can now see why the knee-jerk dismissal of something as “woke” is so nasty; it amounts to a self-righteous choice not only to insult or denigrate others but to protect one’s ignorance and support injustice.

Unless we learn to talk with each other rather than past each other, it’s difficult to see how we can ever achieve peace on Earth or truly show our good will to each other.”

Refuting Wokeness: Clarity Over Obfuscation

Introduction: The Polysemy Trap

Philosophy Professor Letitia Meynell, in her essay on navigating “wokeness,” seeks to foster dialogue about contentious social practices. Yet her analysis falters by overlooking a critical feature of “woke”: its polysemy, which obscures meaning and confounds discourse. The activist Left often deploys poorly defined terms, resisting crystallization into cohesive arguments. This ambiguity is deliberate, enabling the Motte and Bailey strategy—where “woke” advocates defend controversial policies under the guise of innocuous ideals. For supporters, “woke” connotes kindness, empathy, and social awareness; in practice, it can manifest as discrimination against perceived “oppressor” groups. Meynell’s failure to grapple with this duality undermines her vision of mutual understanding, necessitating a sharper critique.

Engaging Meynell’s Core Claims

Meynell posits that “woke interventions” target practices deemed offensive, false, or discriminatory, citing an antisemitic slur used casually during a play audition as a clear case of harm. Her framework, at its strongest, is not a dogmatic defense of all interventions but a call to assess practices critically: might they offend a group, misrepresent them, or perpetuate unjust attitudes? She urges critics to engage intervenors’ perspectives before dismissing their concerns, a reasonable plea for open-mindedness rooted in social psychological research on implicit biases.

Yet this approach stumbles on two counts. First, it ignores the polysemy of “woke,” which allows advocates to glide between benign ideals and coercive measures. A call for inclusive language (the motte) can escalate into punitive actions (the bailey), as seen in the 2018 case of a University of Michigan professor disciplined for refusing to use preferred pronouns, despite no evidence of discriminatory intent. Meynell’s essay elides this slippage, presenting interventions as primarily corrective. Second, her reliance on subjective offense risks overreach. While the antisemitic slur is unequivocally harmful, many “woke” targets—debates over cultural appropriation or microaggressions—hinge on context and interpretation. Absent clear criteria for harm, interventions can stifle discourse, a tension Meynell underestimates.

The Unproven Premise of Systemic Harm

Meynell’s most compelling claim is that “woke interventions” address practices that “implicitly endorse or maintain unjust attitudes,” facilitating discrimination. She invokes implicit bias research to argue that good intentions cannot preclude harm—a point with merit, as biases can operate unconsciously. Yet she assumes systemic harm as axiomatic, demanding critics disprove it rather than requiring proponents to prove it. Research on implicit bias, like the Implicit Association Test (IAT), faces scrutiny for weak predictive validity in real-world behavior (Oswald et al., 2013). Correlation is not causation; asserting that everyday practices inherently perpetuate discrimination requires evidence—say, data linking specific language to measurable disparities. By sidestepping this rigor, Meynell inverts rational inquiry, undermining her call for “honest conversations.”

The Motte and Bailey’s Polarizing Effect

The polysemy of “woke” fuels a rhetorical sleight-of-hand: the Motte and Bailey strategy. In the motte, “woke” is empathy—uplifting the marginalized, fostering inclusion. In the bailey, it justifies policies that alienate or vilify, often without substantiating harm. Consider the 2020 backlash against J.K. Rowling, labeled “transphobic” for questioning gender ideology, despite her nuanced arguments. Such interventions, cloaked in moral righteousness, suppress debate. Meynell’s essay endorses the motte, ignoring the bailey’s divisive impact. A 2021 Cato Institute survey found 66% of Americans fear expressing political views due to social repercussions, suggesting “woke” practices can fracture rather than unite. Polysemy exacerbates this: without shared definitions, dialogue devolves into mutual incomprehension—a debacle Meynell’s framework fails to address.

A Path to True Dialogue

Meynell’s vision of dialogue is laudable but lopsided. She rightly urges critics to consider intervenors’ perspectives, yet spares advocates the same scrutiny. True dialogue demands reciprocity: proponents must substantiate harm with evidence—statistical impacts, not anecdotal offense—while critics must articulate principled objections, such as free speech or empirical skepticism. Meynell’s call for critics to offer “tempered explanations” or apologies assumes intervenors’ claims are prima facie valid, tilting the scales. Dismissing dissent as “nasty” or “self-righteous” poisons discourse, as does the polysemic dodge that shields “woke” policies from critique. A just society requires evidence-based debate: terms defined, assumptions tested, ambiguity exposed.

Conclusion

Meynell’s essay, at its core, aspires to bridge divides through reflection on social practices. Yet it falters by ignoring the polysemy of “woke” and presuming systemic harm without proof. Her prescriptive tone—demanding critics justify dissent while excusing advocates’ vagueness—corrodes the mutual understanding she champions. By dismantling the Motte and Bailey tactic and grounding discourse in evidence, we can forge a society that is both just and cohesive. Clarity, not obfuscation, is the path forward.

References

- Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., & Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(2), 171–192.

- Cato Institute. (2021). National Survey: Americans’ Free Speech Concerns. Retrieved from cato.org.

In this series, we’ve explored the oppressor/oppressed lens—a framework that divides society into those with power (oppressors) and those without (oppressed). The first post traced its roots to the Combahee River Collective, Paulo Freire, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, showing how intersectionality and class consciousness shaped a tool for naming systemic injustice, though Freire’s ideological focus sidelined factual learning. The second post examined its modern applications through Judith Butler’s fluid view of power, Robin DiAngelo’s struggle session-like workshops, and John McWhorter’s critique of its dogmatic turn. While the lens has illuminated real harms, it often oversimplifies morality, fosters division, and stifles dialogue. In this final post, we’ll dig into its deepest limitations with insights from Peter Boghossian, James Lindsay, Jonathan Haidt, bell hooks, and Joe L. Kincheloe. Then, we’ll propose a more nuanced moral framework for navigating our complex world.

The Lens’s Fatal Flaws

The oppressor/oppressed lens promises clarity: identify the oppressor, uplift the oppressed, and justice follows. But in practice, it falters as a universal moral guide. It reduces people to group identities, suppresses critical inquiry, and fuels tribalism, leaving little room for the messy realities of human experience. Five thinkers help us see why—and point toward a better way.

Peter Boghossian: Stifling Inquiry

Peter Boghossian, in How to Have Impossible Conversations (2019), argues that the oppressor/oppressed lens creates ideological echo chambers where questioning is taboo. He describes how labeling someone an “oppressor” based on identity—like race or gender—shuts down dialogue, as dissent is framed as defending privilege. For example, in a college seminar, a student questioning a claim about systemic racism might be silenced with accusations of “fragility,” echoing DiAngelo’s tactics. Boghossian emphasizes that true critical thinking requires open inquiry, not moral litmus tests. The lens’s binary framing discourages this, turning discussions into battles over who’s “right” rather than what’s true. By prioritizing ideology over evidence, it undermines the very understanding it seeks to foster.

James Lindsay: Ideological Rigidity

James Lindsay, through his work in Cynical Theories (2020) and on New Discourses (https://newdiscourses.com/), argues that the oppressor/oppressed lens, rooted in critical theory, imposes a power-obsessed worldview that distorts reality and suppresses dialogue. He contends that the lens reduces every issue—from education to science—to a battle between oppressors and oppressed, deeming “oppressed” perspectives inherently valid and “oppressor” ones suspect. For example, Lindsay cites school restorative justice programs, which often prioritize systemic oppression narratives over individual accountability, leading to increased classroom disruption (New Discourses Podcast, Ep. 160). On X, a scientific study might be dismissed as “colonial” if it challenges the lens, ignoring empirical evidence. Lindsay warns that this creates a moral absolutism where questioning the lens is equated with upholding oppression, stifling reason and fostering division. Like Freire’s class consciousness, this rigid ideology prioritizes narrative over nuance, limiting our ability to address complex problems.

Jonathan Haidt: Moral Tribalism

Jonathan Haidt, in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and The Righteous Mind (2012), shows how the lens fuels moral tribalism—dividing society into “us” (the oppressed or their allies) and “them” (the oppressors). He argues that it amplifies cognitive distortions, like catastrophizing, where minor slights are seen as existential threats. For example, a workplace disagreements might escalate into accusations of “oppression” if framed through the lens, as seen in DiAngelo-inspired DEI sessions. Haidt’s research on moral foundations suggests humans value not just fairness (the lens’s focus) but also loyalty, care, and liberty. By fixating on oppression, the lens neglects these other values, alienating people who might otherwise support justice. This tribalism turns potential allies into enemies, undermining collective progress.

bell hooks: Division Over Solidarity

bell hooks, in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), critiques the oppressor/oppressed lens for fostering division rather than solidarity. She argues that pitting groups against each other—men vs. women, white vs. Black—reinforces hierarchies rather than dismantling them. For hooks, true liberation requires love and mutual understanding, not just naming oppressors. For instance, a feminist movement that vilifies all men as oppressors, as the lens might encourage, alienates male allies and ignores how class or race complicates gender dynamics. hooks’ vision of a “beloved community” emphasizes shared humanity over binary conflict, offering a moral framework that transcends the lens’s zero-sum approach.

Joe L. Kincheloe: Contextual Complexity

Joe L. Kincheloe, in Critical Constructivism: A Primer (2005), offers a nuanced alternative to the oppressor/oppressed lens by emphasizing that knowledge and power are co-constructed through social, cultural, and historical contexts. Building on social constructivism, Kincheloe argues that truth is negotiated through critical dialogue and evidence, not merely a function of power, rejecting the radical relativism that can accompany postmodern interpretations. He advocates empowering students to analyze their realities collaboratively, questioning how power shapes knowledge without reducing issues to a binary of oppressors vs. oppressed. For example, a teacher might guide students to investigate how local economic policies impact their community, fostering shared inquiry that considers multiple perspectives and real-world consequences. Kincheloe critiques universalizing frameworks like the oppressor/oppressed lens for ignoring local nuances and individual agency. By promoting a critical consciousness rooted in contextual, evidence-based analysis, he supports a moral framework that values complexity and collaboration over ideological absolutes.

A Better Way Forward

The oppressor/oppressed lens has illuminated systemic wrongs, from Maya’s workplace barriers to the interlocking oppressions Crenshaw described. But as Boghossian, Lindsay, Haidt, hooks, and Kincheloe show, it falls short as a moral compass. It stifles inquiry, rigidifies thought, fuels tribalism, divides communities, and oversimplifies power. So, what’s the alternative?

A more nuanced moral framework starts with three principles:

- Context Over Categories: Instead of judging people by group identities, consider their actions and circumstances. A white worker struggling with poverty isn’t inherently an “oppressor,” just as a wealthy person of color isn’t automatically “oppressed.” Context, as Kincheloe’s critical constructivism and Butler’s performativity suggest, reveals the fluidity of power.

- Dialogue Over Dogma: Following Boghossian and hooks, prioritize open conversation over moral litmus tests. Ask questions, listen, and assume good faith, even when views differ. This builds bridges, not walls.

- Shared Humanity Over Tribalism: Inspired by hooks and Haidt, focus on common values—care, fairness, resilience—rather than pitting groups against each other. Solutions to injustice come from collaboration, not zero-sum battles.

In practice, this might look like a workplace addressing Maya’s barriers by examining hiring data and fostering inclusive policies, not just hosting struggle sessions. Or an X discussion where users debate ideas with evidence, not identity-based accusations. This framework doesn’t ignore systemic issues—it builds on the lens’s insights—but approaches them with humility, curiosity, and a commitment to unity.

Closing Thoughts

The oppressor/oppressed lens gave voice to the marginalized, but it’s not the whole story. Its binary moralism, as we’ve seen, often divides more than it heals. By embracing context, dialogue, and shared humanity, we can move toward a morality that honors complexity and fosters progress. What do you think of this approach? Share your thoughts in the comments—I’d love to hear how you navigate these issues.

Sources: Peter Boghossian’s How to Have Impossible Conversations (2019), James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose’s Cynical Theories (2020), New Discourses (https://newdiscourses.com/), Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and The Righteous Mind (2012), bell hooks’ Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), Joe L. Kincheloe’s Critical Constructivism: A Primer (2005, p. 23).

Epilogue: Reflecting on Truth and a Path Forward

This series has unpacked the oppressor/oppressed lens, a framework that shapes how we view justice and morality. We traced its roots to intersectionality and class consciousness, explored its modern misuses—from struggle sessions to dogmatic cancellations—and critiqued its limitations with insights on power, tribalism, and solidarity. The lens reveals systemic wrongs, like Maya’s workplace barriers, but its binary moralism often fuels division over dialogue.

We proposed a better way: a moral framework of context over categories, dialogue over dogma, and shared humanity over tribalism. This approach tackles injustice with nuance—think workplaces analyzing hiring data, not just moral confessions, or X debates grounded in evidence, not accusations. It honors complexity while fostering progress.

Why explore these ideas? For me, it’s about pursuing objective truth and working across divides—the only way forward, in my view. The lens’s ideology, from rigid narratives to tribal pile-ons, obscures truth and fractures us. I’m driven to seek truth through reason, as Kincheloe’s critical constructivism urges, and to bridge gaps, as hooks’ beloved community envisions. Truth and unity require tough conversations, not moral absolutes.

I invite you to reflect: How does the lens shape your world? Can we collaborate across divides? Try applying context and dialogue in your next discussion—whether at work or online. Share your thoughts in the comments. Let’s build a path forward together.

Your opinions…