You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Chilliwack Teachers’ Association’ tag.

Tag Archive

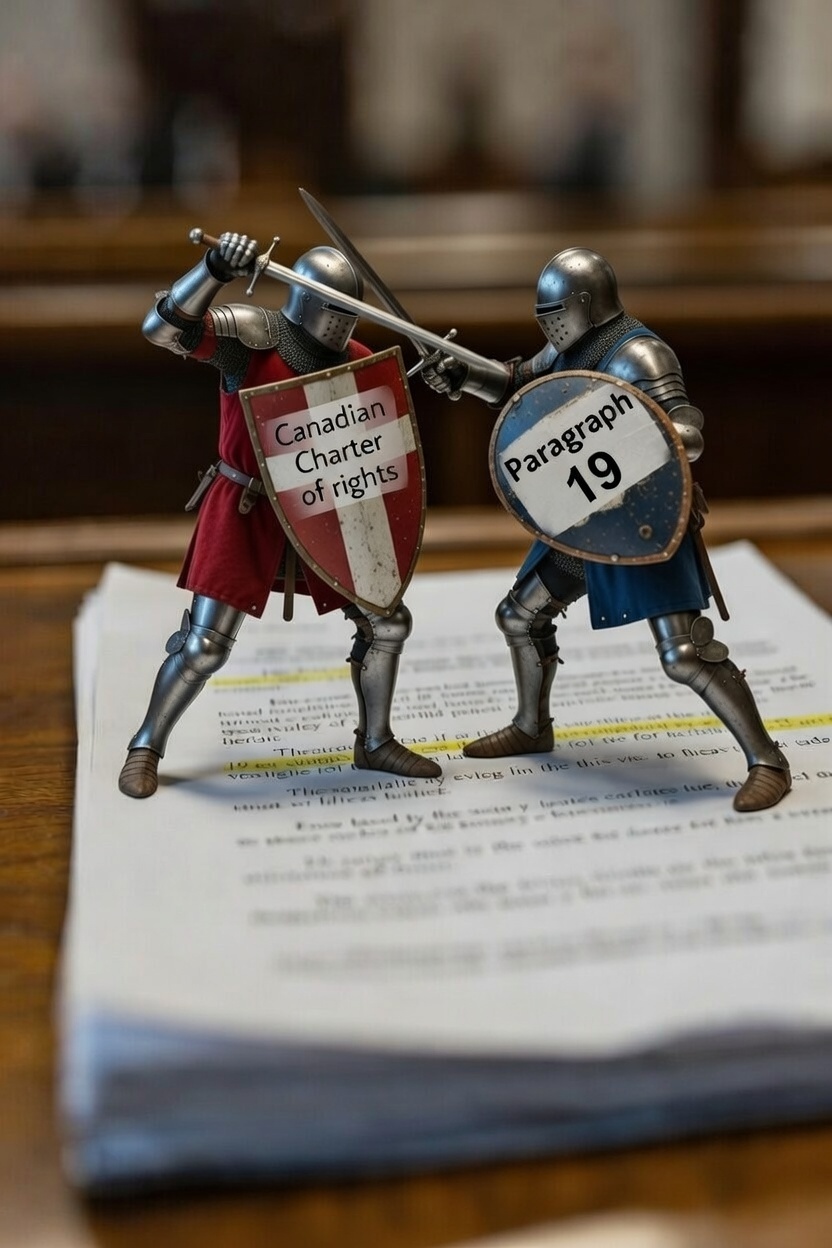

Paragraph 19 and the New Test of “Acceptance” A clinical primer on Chilliwack Teachers’ Association v. Neufeld (No. 10), 2026 BCHRT 49

February 22, 2026 in Canada, Education, Gender Issues, Politics, Public Policy | Tags: Barry Neufeld, BCHRT, British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal, Canadian Law?, Chilliwack Teachers’ Association, Compelled speech, Freedom of Expression, gender identity, Human Rights Law, SOGI 123 | by The Arbourist | 1 comment

The most important part of the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal’s decision in Chilliwack Teachers’ Association v. Neufeld (No. 10) is not the political noise around it. It is a short passage in paragraph 19.

That passage matters because it appears to recode a contested idea as a condition of basic civic recognition. In plain terms, it moves from “do not discriminate against people” toward “you must affirm a specific theory to count as accepting them.”

This primer focuses on that point only. It does not attempt to relitigate the entire case.

The tribunal’s decision was issued February 18, 2026, indexed as 2026 BCHRT 49.

What this article argues in one paragraph

TL;DR: The BCHRT can punish discrimination without requiring Canadians to affirm a contested theory of sex and gender as the price of being considered non-discriminatory. Paragraph 19 matters because it blurs that line: it treats disagreement with a conceptual framework as “existential denial” of a person. That is a legal and civic problem, even for people who support anti-discrimination protections.

What this critique is not saying

Before the legal and logical analysis, a boundary line.

This critique is not saying:

- LGBTQ teachers cannot suffer real harm from public rhetoric.

- Human rights law cannot address discriminatory publications or poisoned work environments.

- Every criticism of SOGI, gender identity policy, or youth transition debates is lawful.

- Barry Neufeld’s rhetoric was prudent, fair, or wise.

The tribunal found multiple contraventions under the Code, including ss. 7(1)(a), 7(1)(b), and 13, and the decision contains detailed findings about workplace impact and discriminatory effects.

This primer makes a narrower claim:

Paragraph 19 uses an analogy that collapses the distinction between recognizing a person and affirming a contested ideological premise.

That distinction matters for free expression, legal clarity, and public trust.

The passage that changes the frame

Here is the core language from paragraph 19 (including the definitional lead-in):

“Transpeople are, by definition, people ‘whose gender identity does not align with the sex assigned to them at birth’…”

“If a person elects not to ‘believe’ that gender identity is separate from sex assigned at birth, then they do not ‘believe’ in transpeople. This is a form of existential denial…”

“A person does not need to believe in Christianity to accept that another person is Christian. However, to accept that a person is transgender, one must accept that their gender identity is different than their sex assigned at birth.”

This is the paragraph Canadians should read for themselves.

The issue is not whether one can be civil. The issue is whether civil recognition is being redefined as mandatory assent to a disputed concept.

The core problem: equivocation on “accept” and “believe”

The tribunal’s analogy uses accept and believe as if they do the same work in both examples. They do not.

Christianity example

In the Christianity example, “accept that another person is Christian” usually means:

- acknowledging a descriptive fact about that person’s profession of faith,

- recognizing what they claim to believe,

- without requiring your own doctrinal agreement.

You can think Christianity is false and still accurately say, “Yes, that person is Christian.”

That is descriptive recognition.

Transgender example (as framed in para. 19)

In the tribunal’s wording, “accept that a person is transgender” is not left at description. It is tied to a required premise:

- that gender identity is separate from sex assigned at birth, and

- that this premise must be accepted in order to count as accepting the person at all.

That is not merely descriptive recognition. It is affirmation of a contested theory built into the definition.

That is the logical shift.

Why this matters legally and civically

A liberal legal order normally distinguishes between:

- Recognition of persons

- Protection from discrimination

- Compelled assent to contested beliefs

Paragraph 19 blurs those lines.

A person can acknowledge all of the following without contradiction:

- that someone identifies as transgender,

- that the person may experience distress, dysphoria, or social vulnerability,

- that harassment or discrimination against them is wrong,

while still disputing:

- whether sex is best described as “assigned” rather than observed,

- whether gender identity should override sex in all legal contexts,

- whether specific policies (sports, prisons, shelters, schools) should follow from that framework.

If disagreement on those latter questions is relabeled as “existential denial,” the public is no longer being asked to tolerate persons. It is being asked to affirm a framework.

That is the warning.

A concrete example most readers can use

Here is the distinction in everyday terms.

A teacher, coach, employer, or colleague can:

- treat a transgender person courteously,

- avoid harassment,

- maintain ordinary workplace civility,

- refrain from discriminatory conduct,

without conceding that sex categories disappear in every policy context.

For example, a person may choose to use a student’s preferred name in daily interaction and still argue that elite female sports should remain sex-based. A person may reject insults and harassment and still dispute whether “sex assigned at birth” is the best scientific language.

That is not incoherence. That is how pluralist societies work.

Paragraph 19 pressures this distinction by framing conceptual dissent as equivalent to non-recognition of the person.

The definitional trap in paragraph 19

Paragraph 19 does something subtle but powerful.

It defines “transpeople” using a specific conceptual framework (“gender identity” versus “sex assigned at birth”), then treats non-acceptance of that framework as non-acceptance of trans people themselves.

That is a question-begging structure:

- Premise (built into the definition): trans identity necessarily means gender identity distinct from sex assigned at birth.

- Conclusion: if you reject that premise, you deny trans people.

But the premise is precisely what is contested in public debate.

A tribunal can rule against discriminatory conduct. It can interpret the Code. It can assess workplace effects. But once it turns a contested framework into the test of whether one “accepts” a class of persons at all, it risks moving from adjudication into ideological gatekeeping.

Context matters, but it does not fix the analogy

To be fair to the decision, the tribunal is not writing in a vacuum.

The reasons frame Mr. Neufeld’s rhetoric as part of a broader pattern of statements the tribunal found denigrating, inflammatory, and connected to the work environment of LGBTQ teachers. The tribunal also found a direct connection between his public rhetoric and a school climate that felt unsafe to many LGBTQ teachers.

That context may explain the tribunal’s forceful language.

It does not solve the logic problem in paragraph 19.

Even in hard cases, legal reasoning should preserve key distinctions:

- personhood vs. theory,

- conduct vs. belief,

- discrimination vs. disagreement.

When those lines blur, institutions may satisfy partisans while losing credibility with ordinary readers who can still detect the category error.

Remedies matter too (and should be stated plainly)

This was not a symbolic ruling.

The tribunal ordered multiple remedies, including a cease-and-refrain order, $442.00 to Teacher C for lost wages/expenses, and a $750,000 global award for injury to dignity, feelings, and self-respect to be paid to the CTA for equal distribution to class members. It also ordered interest on monetary amounts as specified.

The tribunal also states that the dignity award is compensatory and “not punitive.”

Readers can disagree about the amount. They should still understand that paragraph 19 sits inside a decision with real legal and financial consequences.

Why Canadians should pay attention

Most Canadians will never read a tribunal decision. They will hear summaries.

That is why paragraph 19 deserves attention.

If public institutions begin treating disagreement with a contested theory as “existential denial,” the zone of legitimate disagreement shrinks by definition. The public is no longer told only, “Do not discriminate.” It is told, in effect, “Affirm this framework, or your dissent may be treated as denial of persons.”

That is not a stable basis for pluralism.

A rights-respecting society needs a better rule:

- protect people from discrimination,

- punish actual harassment and unlawful conduct,

- preserve space for lawful disagreement on contested concepts.

Paragraph 19, as written, weakens that line.

Glossary for readers

Paragraph 19

A specific paragraph in the tribunal’s reasons that contains the Christianity analogy and the “existential denial” language. This primer focuses on that paragraph.

“Existential denial”

The tribunal’s phrase in para. 19 for refusing to “believe” that gender identity is separate from sex assigned at birth, which it links to not “believing in transpeople.”

Section 7(1)(a) (BC Human Rights Code)

A Code provision dealing with discriminatory publications (as applied by the tribunal in this case).

Section 7(1)(b) (BC Human Rights Code)

A Code provision dealing with publications likely to expose a person or group to hatred or contempt (the tribunal found some publications met this threshold).

Section 13 (BC Human Rights Code)

A Code provision dealing with discrimination in employment, including discriminatory work environments (the tribunal found a poisoned work environment for the class of LGBTQ teachers).

“Poisoned work environment”

A human rights / employment law concept referring to a workplace atmosphere made discriminatory through conduct, speech, or conditions connected to protected grounds.

SOGI 1 2 3

Resources discussed in the decision in connection with BC public education and inclusion policies; the tribunal notes they are resources and addresses their role in the factual background. (See source map below.)

Source map so readers can verify for themselves

Use this map to read the decision directly and check each claim the PDF is available here.

Case identification and issuance

- Paras. 1–3 (intro/citation/date/caption)

- Verified from the front matter: issued February 18, 2026, indexed as 2026 BCHRT 49.

Overview of findings and what was decided

- Paras. 4–6 (high-level findings; which Code sections were violated)

- Tribunal later reiterates finding the complaint justified in part and violations of ss. 7(1)(a), 7(1)(b), and 13.

Freedom of expression framework / limits

- Paras. 8–10 (overview-level framing)

- Also see Part VII heading “Freedom of expression and its limits” in the table of contents.

SOGI factual background

- Paras. 13–15 (background on SOGI 1 2 3 in public education)

- See TOC references to “SOGI 1 2 3 in public education” and Neufeld’s response.

The key analogy and “existential denial”

- Para. 19 (full lead-in + Christianity analogy + “existential denial” language)

This is the central paragraph for the primer.

Tribunal’s “veneer of reasonableness” concern

- Para. 19 (same paragraph; immediate context of the analogy)

Workplace impact evidence / climate findings

- Paras. 38 onward (teacher evidence and climate effects)

- Example evidence and findings on climate and workplace effects are reflected in the teacher testimony excerpts and the tribunal’s acceptance of a direct connection to unsafe school climate.

s. 13 conclusion (employment discrimination)

- Para. 82 (and surrounding paras.) / section conclusion in Part V-C

- Tribunal concludes violation of s. 13 for the class.

Remedies overview (s. 37(2))

- Paras. 99 onward (remedies discussion starts in the remedies part)

- Includes declaration, cease/refrain order, expenses, dignity award, and interest.

Cease and refrain order

- Remedies section, Part A (paras. around 100–101)

- “We order him to cease the contravention and refrain from committing the same or a similar contravention…”

Training remedy requested but declined

- Part B (ameliorative steps) (paras. around 102)

- Tribunal says it was not persuaded mandatory training would have a beneficial effect in this case.

Teacher C expenses ($442)

- Part C (expenses incurred) (paras. around 103)

- Tribunal orders $442.00 to Teacher C.

Dignity award ($750,000 global)

- Part D (compensation for injury to dignity…) (paras. around 104–111)

- Tribunal says the purpose is compensatory, not punitive; later orders $750,000 to the CTA for equal distribution to class members.

Interest orders

- Part E (Interest) (paras. around 112)

- Tribunal orders interest as set out in the Court Order Interest Act.

Your opinions…