You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Cultural Hegemony’ tag.

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist imprisoned by Mussolini, changed political strategy forever by shifting revolution from the factory floor to the realm of culture. His concept of cultural hegemony—the quiet capture of schools, media, and moral institutions—remains the blueprint for the modern Left’s “long march through the institutions.” Understanding him is key to understanding how ideology became the new battlefield of Western democracy.

Why the twentieth century’s most subversive Marxist remains essential to understanding our political moment.

Antonio Gramsci has become a ghostly presence in today’s politics—invoked by both left and right, praised as a prophet of cultural liberation and blamed as the architect of “Cultural Marxism.” Yet few who use his name understand the subtlety of what he actually proposed. Gramsci, an Italian communist jailed by Mussolini from 1926 until his death in 1937, recognized that Western societies could not be overthrown by economic revolution alone. The real battleground, he argued, lay in the culture—in the stories a society tells itself about who it is, what it values, and what it considers “common sense.”

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci dissected how ruling elites maintain power not only through economic control or state coercion but through the manufacture of consent—what he called cultural hegemony. When the public unconsciously accepts elite norms as their own, open coercion becomes unnecessary. The power structure endures because people cannot easily imagine alternatives.

From Marx to Culture: The Pivot that Changed the Left

This insight quietly revolutionized the Marxist project. Where Marx saw power rooted primarily in economics, Gramsci saw it reproduced through education, religion, art, the press, and civic institutions—what he called “civil society.” If these were the true engines of social continuity, then a revolutionary movement must capture them before capturing the state. The task, therefore, was not simply to seize the means of production but to seize the means of persuasion.

That shift—from factory to faculty, from economics to ideology—birthed what would later be called Cultural Marxism. It gave rise to the post-war New Left and, through the Frankfurt School, to a range of “critical” theories that continue to shape university life and activist politics. Power was no longer viewed as residing primarily in class relations but in language, identity, and culture. Gramsci’s “war of position”—a slow, patient infiltration of cultural institutions—became the model.

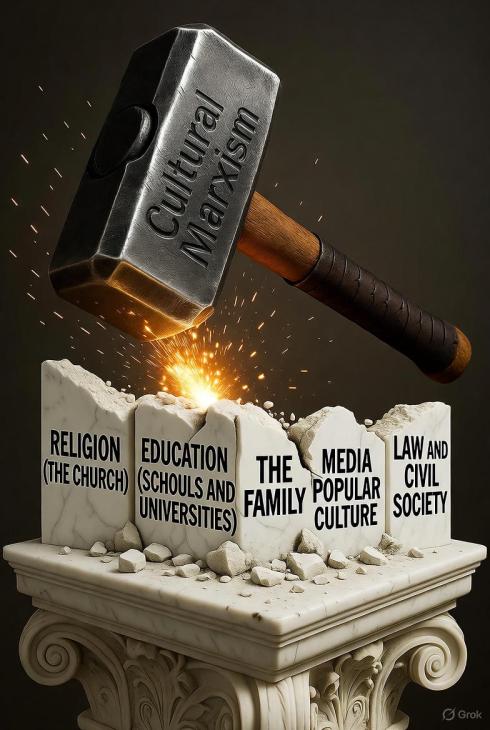

The Five Fronts of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci never offered a neat checklist, but his writings identify five interlocking domains where the battle for hegemony is fought—and where Western institutions have since seen the most visible transformations:

- Religion and Moral Order – For centuries, the Church anchored Western moral consensus. Gramsci saw it as the spiritual foundation of bourgeois power. Undermining or secularizing that foundation was essential to remaking moral consciousness.

- Education and the Intelligentsia – Schools and universities, he observed, do not merely transmit knowledge; they reproduce ideology. Control the curriculum, train the teachers, shape the young—and you shape tomorrow’s society.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, cinema, art, and now digital media cultivate public sentiment. Altering how people speak, joke, and imagine themselves can shift the moral vocabulary of an entire civilization.

- Civil Society and Voluntary Institutions – Clubs, unions, NGOs, and advocacy groups form the connective tissue between individuals and the state. They generate the “organic intellectuals” who articulate a new worldview and lend legitimacy to political change.

- Law, Politics, and the Administrative State – Finally, cultural transformation must be consolidated through legal norms, policy, and bureaucratic language, ensuring that the new values become institutional reflexes rather than contested ideas.

Each domain is a theatre in the long “war of position.” The aim is not an immediate coup but the gradual erosion of inherited norms until the revolutionary outlook feels like common sense.

Why Gramsci Still Matters

Gramsci’s legacy is paradoxical. His analysis was intellectually brilliant—but by detaching revolution from economics and anchoring it in culture, he supplied future radicals with a strategy for subverting liberal democracy from within. The New Left of the 1960s and its academic descendants adopted his playbook, translating class struggle into struggles over race, gender, language, and identity. In this sense, Gramsci stands as both the diagnostician and the progenitor of our current ideological turbulence.

For those tracing the lineage of today’s cultural battles, reading Gramsci is essential. His theory of hegemony explains why institutions that once served as stabilizing forces—universities, churches, professional guilds, and even the arts—have become arenas of moral and political conflict. It also clarifies why dissenters within those institutions are treated not as intellectual adversaries but as heretics.

Reading the Intellectual Landscape

This essay continues the Learning the Lay of the Land series here at Dead Wild Roses, which maps the ideas that reshaped Western political thought:

- Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism — how ideological certainty breeds totalitarian temptation.

- Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and the Birth of Cultural Hegemony — a deep dive into his original ideas.

- Orwell’s Politics and the English Language — how linguistic corruption becomes political control.

- Mill’s On Liberty — a defence of intellectual freedom against the new orthodoxy.

Together they outline the terrain of our ideological crisis: from Arendt’s warning about totalitarian habits of mind, through Gramsci’s theory of cultural capture, to Orwell’s exposure of linguistic manipulation and Mill’s insistence on free thought.

Closing Reflection

Gramsci’s insight—that the health of a society depends on who defines its common sense—remains the axis on which our modern conflicts turn. Understanding his ideas is not an act of homage, but of inoculation. To preserve a free and open civilization, one must know precisely how it can be subverted—and Gramsci told us, in meticulous detail, how that can be done.

Primary Sources

Gramsci, Antonio. *Selections from the Prison Notebooks*. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971. (Core text for concepts of cultural hegemony, war of position, civil society, and organic intellectuals; selections from Notebooks 1–29, written 1929–1935.)

Secondary Sources

Arendt, Hannah. *The Origins of Totalitarianism*. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. (Referenced in series context for ideological escalation into totalitarianism.)

Mill, John Stuart. *On Liberty*. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859. (Referenced in series context as counterpoint to hegemonic orthodoxy.)

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” *Horizon* 13, no. 76 (April 1946): 252–265. (Referenced in series context for linguistic mechanisms of ideological control.)

Additional Contextual Works

Jay, Martin. *The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950*. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973. (Provides linkage between Gramsci’s cultural pivot and post-war Critical Theory.)

Rudd, Mark. “The Long March Through the Institutions: A Memoir of the New Left.” In *The Sixties Without Apology*, edited by Sohnya Sayres et al., 201–218. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. (Illustrates practical adoption of Gramscian strategy in 1960s activism.)

Your opinions…