You are currently browsing the monthly archive for January 2026.

Attribution: This essay is a paraphrase-and-critique prompted by James Lindsay’s New Discourses Podcast episode “What Woke Really Means.” Any errors of interpretation are mine. (New Discourses)

“Woke” is a word that now means everything and nothing: insult, badge, shibboleth, brand. That’s why it’s worth defining it narrowly before arguing about it. I’m not using “woke” to mean “progressive,” “civil-rights liberal,” “any activism,” or “anyone who thinks injustice exists.” I mean a specific machine: a moral–political pattern that turns social friction into group-based identity, and then turns group-based identity into a special way of knowing. When that pattern is present, the downstream politics are unusually predictable.

The first engine is entitlement turned into alienation. Start with a felt ought: people like me should be able to live, speak, belong, succeed, and be recognized in a certain way. That ought can be reasonable. Some groups really have been locked out of full participation. Institutions really do gatekeep. Norms really do punish outsiders. The pivot is what you do with the mismatch between “ought” and reality. The woke machine teaches that the mismatch is not mainly a mix of tradeoffs, chance, imperfect policy, individual bad actors, or local failures. It is alienation, a structural condition imposed by an illegitimate power arrangement. Your frustration is not merely about outcomes. It becomes about being denied your proper mode of existence. Once alienation is framed that way, it stops being a problem to solve and becomes an identity to inhabit.

That identity shift is the real move. The self is quietly demoted from “individual with rights and duties” to “representative of a class in conflict.” You begin to think in group nouns first: oppressed/oppressor, marginalized/privileged, normal/deviant, colonized/colonizer. This is why identity politics shows up so reliably. It is a downstream output of a prior decision to interpret the world through group-alienation. It can even masquerade as humility. “I’m just listening to marginalized voices.” But it performs a different operation. Moral standing relocates from argument to position. You don’t merely hold beliefs. You become a bearer of a collective grievance, and that grievance grants a kind of authority in advance.

The second engine is epistemic: knowledge becomes positional. Again, the starting observation can be true enough. Institutions reward certain ways of speaking. Credentialing filters who gets heard. Consensus is sometimes wrong. Lived experience can surface facts that statistics miss. The woke machine turns those observations into a total explanation. The established “knowing field” is not just fallible, but hegemonic. It is treated as a knowledge regime that functions to protect power.

There is an honest version of this impulse. Marginalized people can notice things insiders miss. Testimony can expose local abuses that institutions quietly normalize. Suspicion of official narratives is sometimes warranted. History is full of respectable consensus that later looks like rationalized cruelty. In that sense, privileging marginalized voices can function as a corrective. The problem begins when “corrective” hardens into a standing hierarchy of credibility, and when the moral value of hearing becomes a substitute for the epistemic work of checking. At that point, the method stops being a tool for truth and becomes a tool for power.

Once you accept the hegemonic frame as total, a standing preference follows. “Counter-hegemonic” claims, those said to come from the margins or said to be suppressed, are treated as inherently more trustworthy, or at least more morally protected. The point isn’t always truth. Often it’s leverage. If a claim destabilizes the legitimacy of the system, it gets treated as epistemically special.

You can see how this becomes self-sealing. Consider a common pattern: demographic observation, then a moralized system interpretation, then an appeal to lived experience, then immunity from counterargument. “I notice a space is mostly white.” Fine. “Therefore hiking is racist.” That is not observation but diagnosis. If challenged, the claim can retreat into experience: “I feel unsafe,” “my lived experience says otherwise.” Any dissent is then reclassified as proof of the system’s blindness. The disagreement is not processed as information. It becomes further evidence of hegemony. At that point, you’re no longer arguing about the world. You’re litigating the moral status of who gets to describe it.

Put these two engines together, alienation-as-identity and positional knowing, and the political outputs stop looking like random bad behavior. If your group’s situation is existential, ordinary ethics begin to look like luxuries written by your enemy. Double standards don’t feel like hypocrisy. They feel like “context.” Coercive tactics don’t feel like power-seeking. They feel like self-defense. “Allies” become morally sorted people who accept the frame. “Enemies” become those who refuse it. Because the machine treats knowledge as power, controlling speech and institutions can be rationalized as protecting truth rather than enforcing conformity.

So here’s a clean diagnostic that avoids cheap mind-reading. It’s not “woke” to notice injustice, organize, protest, or advocate. It becomes woke in this sense when three conditions appear together:

- Ontological grievance: your primary identity is a group-based injury story. Who you are is mainly who harmed “your people.”

- Positional epistemology: the status of a claim depends heavily on who says it, not what can be shown. Identity outranks argument.

- Self-sealing reasoning: disagreement is treated as proof of harm or hegemony, making correction impossible.

Any one of these can show up in ordinary politics. “Woke,” in this narrow sense, is when they lock together and become a stable identity system.

That triad is the machine. Once it’s operating, it tends to erode the conditions that let pluralistic societies function: shared standards of evidence, equal moral agency, and the ability to disagree without being treated as morally contaminated. In its best moments, the impulse can push institutions to see what they ignored and to repair what they excused. But a politics that begins as reform can slide into a politics that needs conflict as fuel. Once conflict becomes fuel, the temptation is obvious. Keep the wound open. Keep the epistemic gate locked. Keep the enemy permanent. If the machine ever stops, the identity it built starts to dissolve. 🔥

Glossary 📘

Alienation

A felt separation from what you believe you should rightfully be or have. In this framework: not mere disappointment, but a condition allegedly imposed by an illegitimate system.

Entitlement claim

A “felt ought”: a belief that people like me (or my group) are owed a certain kind of recognition, access, or outcome. Not automatically “spoiled,” just the moral premise that something is due.

Group-based identity

A primary self-concept built around membership in a social category (race/sex/class/nation, etc.), especially when that category is framed as locked in conflict with another.

Identity politics

Politics organized primarily around group membership and group conflict rather than individual rights, shared citizenship, or policy compromise.

Ontology / ontological grievance

Ontology is “what you are.” Ontological grievance is when grievance becomes core to being: the self is primarily defined as an injured member of an alienated group.

Epistemology / positional epistemology

Epistemology is “how we know.” Positional epistemology is when the credibility of claims depends heavily on the speaker’s identity position, rather than evidence and argument.

Hegemony / hegemonic knowledge

The idea that a society’s “common sense” and official knowledge are shaped to preserve existing power. “Hegemonic knowledge” is what the system allegedly allows as legitimate truth.

Counter-hegemonic / marginalized claims

Claims presented as outside the dominant “knowing field,” often treated as morally protected or more trustworthy because they challenge the status quo.

Lived experience

First-person testimony about what life is like. Valuable as evidence of experience; controversial when treated as unquestionable authority on broad causal explanations.

Self-sealing reasoning

A reasoning pattern where counterevidence is reinterpreted as evidence for the claim (for example, “your disagreement proves the system’s bias”), making the claim hard to correct.

Friend–enemy politics

A posture that sorts people into allies and enemies in a moralized way, where dissent feels like threat rather than disagreement.

Exception ethics

A moral logic where ordinary standards like fairness, consistency, and procedural restraint are suspended because the situation is framed as existential.

Endnotes

- James Lindsay, “What Woke Really Means,” New Discourses Podcast (New Discourses, January 21, 2026). (New Discourses)

- “What Woke Really Means,” New Discourses (audio hosting/episode metadata). (SoundCloud)

- Joe L. Kincheloe, Critical Constructivism Primer (Peter Lang, 2005). (Peter Lang)

- Özlem Sensoy and Robin DiAngelo, Is Everyone Really Equal? An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education, 2nd ed. (Teachers College Press, 2017). (tcpress.com)

- Helen Pluckrose and James A. Lindsay, Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody (Pitchstone Publishing, 2020). (ipgbook.com)

Story synopsis: For those unfamiliar with the language, this video helps tell the song’s funny story of a young woman, Marie Madeleine, who has a rather difficult relationship with her father’s mischievous little black cow. Dressed in a little checkered skirt and fitted petticoat, Marie tries to milk the cow but finds that it not only produces sour milk, but constantly tries to corner her. Though she manages to tie the cow up, it escapes and tosses her into a pile of manure. When she gets up, she is such a mess it takes her three days to clean herself up!

Modern psychology has a recurring weakness. It periodically falls in love with stories that feel morally urgent, then struggles to unwind them when the evidence turns out thin. That is not because psychologists are uniquely foolish. It is because the field studies messy human beings with noisy measures, ambiguous constructs, and strong social incentives. In that environment, a persuasive narrative can get promoted into “settled science” long before it is actually settled.

The replication crisis is the clearest public sign of this vulnerability. The Reproducibility Project’s large collaboration tried to replicate 100 psychology studies and found much weaker effects and far fewer statistically significant replications than the original literature suggested. (Science) Methodologists also showed how flexible analysis choices and reporting can inflate false positives unless stricter norms are enforced. (SAGE Journals) Meehl’s older critique still lands for the same reason: in “soft” areas of psychology, theories often fade away rather than being cleanly tested and retired. (Error Statistics Philosophy) The implication is not nihilism. It is epistemic humility, especially for claims that are politically charged and personally consequential.

Psychology’s history offers examples of ideas that persist on social momentum long after the evidence grows cloudy. The “memory wars” around repressed and recovered memories show how a compelling clinical narrative can endure in practice while mechanisms remain disputed, and how suggestion can complicate confident storytelling. (PMC) Lilienfeld and colleagues made the broader point in a different domain: weak measurement, loose constructs, and credulous clinical fashions predict confident claims that later demand painful correction. (Guilford Press) The pattern is simple: psychology is unusually prone to ideas becoming socially protected before they are empirically solid.

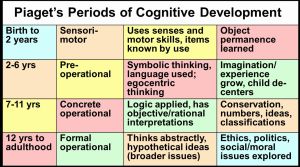

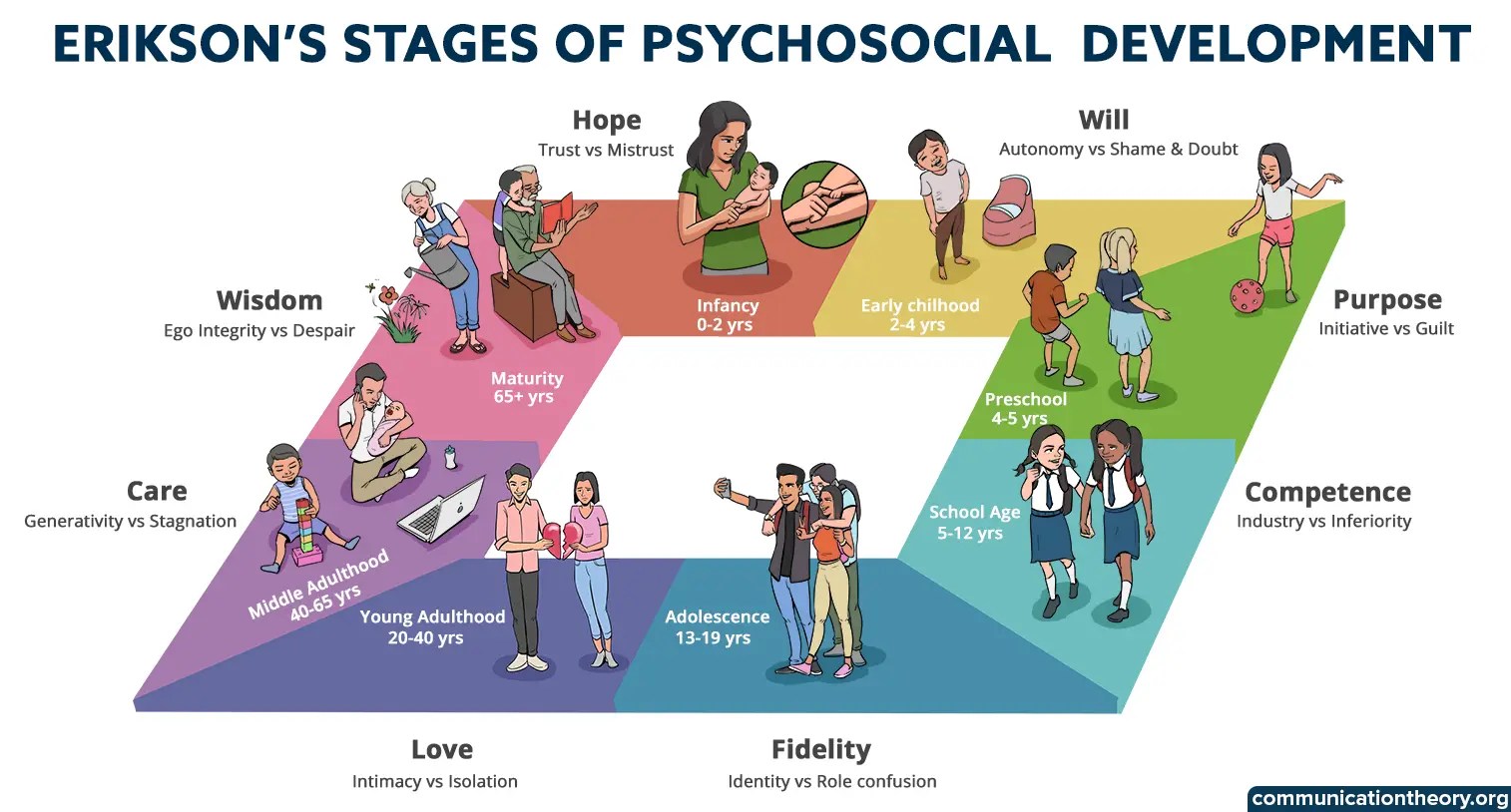

That is the right context for the strong activist version of “innate gender identity,” meaning the claim that very young children can reliably know and articulate a fixed inner gender that may mismatch their body, and that this knowledge should be treated as stable guidance for major decisions. Developmentally, this is exactly the kind of adult projection Piaget and Erikson warn against: treating children’s words as if they carry stable adult concepts while the child’s understanding and self-organization remain socially shaped and changeable. Even within clinical samples, trajectories are not uniform; intensity of childhood gender dysphoria is one known factor associated with persistence into adolescence, which is another way of saying early self-labels do not function like a universal diagnostic oracle. (PubMed) Clinically, the major classification systems are more cautious than the slogans: DSM-5-TR defines gender dysphoria around clinically significant distress or impairment, not the mere existence of an identity claim. (American Psychiatric Association) ICD-11 moved gender incongruence out of the mental disorders chapter and into “conditions related to sexual health,” partly to reduce stigma while preserving access to care. (World Health Organization)

The evidence environment around youth gender medicine shows why fad dynamics matter. The Cass Review argued the evidence base for medical interventions in minors is limited and often low certainty, urging caution and better research. (Utah Legislature) Substantial critiques dispute Cass’s methods and interpretation, which itself signals this is not a stable, high-consensus evidentiary domain. (PMC) The adult responsibility is therefore straightforward: treat childhood self-labels as developmentally real but conceptually limited; separate distress from metaphysics; demand the same evidentiary standards you would demand anywhere else in medicine; and resist turning a contested construct into a moral absolute. If psychology keeps rewarding certainty over rigor, the cost will not be merely bad theory. It will be policy and clinical practice that harden too early, then harm real people when the correction finally arrives.

Glossary

- Replication / reproducibility: Whether an independent team can rerun a study and obtain broadly similar results. (Science)

- Researcher degrees of freedom: The many choices researchers can make (when to stop collecting data, which outcomes to report, which analyses to run) that can unintentionally inflate “significant” findings. (SAGE Journals)

- P-hacking: Informal term for exploiting analytic flexibility to chase statistical significance. (SAGE Journals)

- Construct validity: Whether a measure actually captures the concept it claims to measure (not just something correlated with it). (General measurement concern emphasized in clinical-science critiques.) (Guilford Press)

- Gender dysphoria (DSM-5-TR): Clinically significant distress or impairment related to gender incongruence; not all gender-diverse people have dysphoria. (American Psychiatric Association)

- Gender incongruence (ICD-11): ICD-11 category placed under “conditions related to sexual health,” moved out of the mental disorders chapter. (World Health Organization)

- Persistence (in childhood GD research): Continued gender dysphoria into adolescence; research suggests persistence is not uniform, and intensity is one associated factor. (PubMed)

Short endnotes (audit-friendly)

- Replication crisis anchor: Open Science Collaboration (2015), Science; effects in replications notably smaller; fewer significant replications. (Science)

- Analytic flexibility / false positives: Simmons, Nelson & Simonsohn (2011), “False-Positive Psychology.” (SAGE Journals)

- Soft-psychology theory fade-out critique: Meehl (1978), “Theoretical Risks and Tabular Asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the Slow Progress of Soft Psychology.” (Error Statistics Philosophy)

- Memory wars as an example of contested clinical narratives: Otgaar et al. (2019, PMC) on repression controversy; Loftus (2006) review on recovered/false memories; Loftus (2004) in The Lancet on the continuing dispute. (PMC)

- Clinical-science warning about fads/pseudoscience: Lilienfeld et al., Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology (Guilford excerpts / volume). (Guilford Press)

- DSM-5-TR framing: APA overview and DSM-related materials emphasize distress/impairment as the diagnostic core. (American Psychiatric Association)

- ICD-11 move and rationale: WHO FAQ; supporting scholarly rationale for moving gender incongruence out of mental disorders while preserving access to care. (World Health Organization)

- Persistence factor (intensity): Steensma et al. (2013) follow-up: intensity of childhood GD associated with persistence. (PubMed)

- Cass Review debate: Cass Review final report PDF (archived copies); published critiques and responses indicating contested interpretation and ongoing debate. (Utah Legislature)

Erik Erikson is still useful because he blocks a modern temptation: reading a child’s self-descriptions as evidence of a finished, stable identity. For Erikson, identity is not an inner essence that appears early and then merely announces itself. It is something built across time under social conditions. Relationships, cultural scripts, permissions, limits, and feedback all shape what a person can plausibly become and what they can sustain. If you want a single takeaway, it is this: adults regularly project mature coherence onto children whose sense of “who I am” is still under construction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Erikson’s framework is psychosocial. He describes eight broad stages across the lifespan, each organized around a tension between two outcomes. The point is not a one-time pass or fail. It is a developmental task that tends to recur in new forms as life changes. When conditions are supportive, people lean toward the positive resolution and develop an associated strength or “virtue.” When conditions are hostile or mismatched, the negative pole can dominate and leave a durable vulnerability. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

In early childhood, the tasks are basic but not trivial. In infancy, trust versus mistrust is shaped by whether care is reliable and responsive. In toddlerhood, autonomy versus shame and doubt turns on whether a child can attempt self-control without being humiliated for mistakes. In the preschool years, initiative versus guilt turns on whether exploration and planning are welcomed or punished. These are not destiny. They are early patterns. They set default expectations about safety, agency, and permission that can be reinforced later or revised by later experience. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

School age brings industry versus inferiority. Children now meet the world of tasks, standards, and comparison. Competence grows when effort produces mastery and feedback is fair. Inferiority grows when failure is repeated, demands are mismatched, or judgment is harsh. This matters because it supplies the raw materials for adolescence. Identity versus role confusion is not about picking a label. It is about synthesizing roles, values, loyalties, and a changing body into something that feels continuous and workable. Researchers made this more testable by focusing on processes like exploration and commitment (roughly, trying roles out and then making durable choices), yielding familiar identity-status patterns such as diffusion, foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement. Longitudinal work also supports the commonsense point that identity development extends beyond the teen years for many people. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Erikson’s model deserves the criticisms it often receives. The stages function best as descriptive heuristics rather than strict schedules, and some concepts are hard to measure cleanly. The framework also reflects mid-20th-century Western assumptions, and feminist scholarship has pressed on its gendered blind spots. Still, the core insight survives: selfhood is social before it is philosophical. Children become “someone” through attachment, modeling, constraint, opportunity, and recognition. The practical reminder is blunt, feeding directly into today’s debates. Do not read adult-level identity stability into young children’s words or preferences. Much of what looks like certainty in a child is a snapshot of roles and reinforcement, not proof of a permanent inner core. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

Glossary

- Psychosocial stage/task: A recurring developmental challenge shaped by social context, not a biological timer. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Virtue (Erikson): A strength associated with a relatively positive resolution of a stage task (e.g., hope, will, competence, fidelity). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity vs role confusion: The adolescent task of developing a workable sense of continuity across roles, values, and future direction. (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Identity statuses (Marcia tradition): A research approach using exploration and commitment to classify patterns like diffusion (low both), foreclosure (commitment without exploration), moratorium (exploration without commitment), and achievement (exploration leading to commitment). (Wikipedia)

Endnotes

- Erikson stages overview, virtues, and the “not pass/fail” framing: StatPearls (Orenstein, 2022). (The Psychology Notes Headquarters)

- Scholarly overview and modern framing of Erikson as a lifespan theory: Syed & McLean (2017, PsyArXiv).

- Identity-status trajectories and measurement of exploration/commitment over time: Meeus (2011, PMC). (Wikipedia)

- Marcia identity-status grounding in Eriksonian identity crisis: foundational identity-status paper (PDF record).

- Feminist critique and gender-bias discussion of Eriksonian identity: Sorell (2001).

Jean Piaget is still worth reading because he blocks a common adult mistake: treating children’s words as if they carry adult concepts. Children do not merely know fewer facts. They use different cognitive tools at different ages, and those tools change what their categories can mean. That matters whenever adults take a child’s self-label and translate it into a fixed inner essence. Piaget’s basic warning is simple: the same vocabulary can sit on top of a different kind of understanding, and adults are very good at smuggling their own meanings into what a child says. The rest of his theory is an attempt to explain why that translation error is so easy to make.

Piaget’s machinery for explaining the gap is spare and still useful. Children build schemas, mental frameworks for understanding objects, actions, and categories. They update those schemas through assimilation, which fits new experience into an existing framework, and accommodation, which changes the framework when the fit fails. The friction between “make it fit” and “change the model” is not a bug. It is the engine. Piaget calls the longer-term settling of that friction equilibration, the push toward a workable balance where the child’s model of the world holds together and predicts better.

Piaget is best known for his four-stage outline. In the sensorimotor stage (birth to about 2), infants learn through perception and action, and one classic milestone is object permanence, the idea that things still exist when out of sight. In the preoperational stage (about 2 to 7), children gain symbolic thought: language, pretend play, mental imagery. They also show characteristic limits on many tasks, including egocentrism in perspective-taking and failures of conservation (for example, thinking a taller glass has “more” of the same liquid).

Those limits are real, but they are not always as simple as “the child cannot do it.” Modern researchers have shown that the timing can shift when you change the method. Studies using “violation-of-expectation” designs often find signs of earlier object knowledge than Piaget’s original search tasks detected. The clean takeaway is not that Piaget collapses. It is that measurement matters. Some tasks load children with extra demands (motor planning, inhibition, working memory) that can hide understanding that is present in a simpler form. Task demands can mask competence.

In the concrete operational stage (about 7 to 11), children become capable of logical operations tied to tangible situations. Conservation stabilizes, classification becomes more systematic, and seriation appears more reliably, as when a child can order sticks from shortest to tallest without guesswork. In formal operational thought (roughly adolescence onward, and unevenly across people and domains), abstract and hypothetical reasoning becomes more consistent. Even here, performance can be uneven across closely related tasks, a pattern discussed under the label horizontal décalage. That unevenness is a warning against treating stages as rigid ceilings. Read them instead as a map of typical reorganizations in thinking: a useful guide to what changes, and when, without pretending every child hits every milestone on the same schedule. The practical payoff is blunt. When adults treat a child’s words as adult-level commitments, they risk importing meanings the child has not yet built.

Glossary

- Schema: A mental framework for organizing and interpreting experience.

- Assimilation: Fitting new experience into an existing schema.

- Accommodation: Modifying a schema when the old one does not fit.

- Equilibration: The balancing process that restores or maintains cognitive stability through assimilation and accommodation.

- Object permanence: Understanding that objects continue to exist when hidden.

- Conservation: Understanding that quantity stays the same despite changes in appearance if nothing is added or removed.

- Horizontal décalage: Uneven mastery across related tasks; competence does not arrive all at once.

Endnotes

- Encyclopedia Britannica — Piaget overview: stages, age ranges, and constructivist framing.

- APA Dictionary of Psychology — Piagetian terms: schema, assimilation, accommodation.

- APA Dictionary of Psychology — “Equilibration” definition.

- Baillargeon, Spelke & Wasserman (1985) — early object knowledge via violation-of-expectation methods (PubMed record and related materials).

- Lourenço (2016) — stages as conceptual tools/heuristics (ScienceDirect).

- Neo-Piagetian review discussing horizontal décalage and unevenness as a complication for strict stage-uniformity (UCL Press journals).

Canada is in the middle of a familiar temptation: the Americans are difficult, therefore the Chinese offer must be sane.

The immediate backdrop is concrete. On January 16, 2026, Canada announced a reset in economic ties with China that includes lowering barriers for a set number of Chinese EVs, while China reduces tariffs on key Canadian exports like canola. (Reuters) Washington responded with open irritation, warning Canada it may regret the move and stressing Chinese EVs will face U.S. barriers. (Reuters)

If you want a simple, pasteable bromide for people losing their minds online, it’s this: the U.S. and China both do bad things, but they do bad things in different ways, at different scales, with different “escape hatches.” One is a democracy with adversarial institutions that sometimes work. The other is a one-party state that treats accountability as a threat.

To make that visible, here are five egregious “hits” from each—then the contrast that actually matters.

Five things the United States does that Canadians have reason to resent

1) Protectionist trade punishment against allies

Steel/aluminum tariffs and recurring lumber duties are the classic pattern: national-interest rhetoric, domestic political payoff, allied collateral damage. Canada has repeatedly challenged U.S. measures on steel/aluminum and softwood lumber. (Global Affairs Canada)

Takeaway: the U.S. will squeeze Canada when it’s convenient—sometimes loudly, sometimes as a bureaucratic grind.

2) Energy and infrastructure whiplash

Keystone XL is the poster child of U.S. policy reversals that impose real costs north of the border and then move on. The project’s termination is documented by the company and Canadian/Alberta sources. (TC Energy)

Takeaway: the U.S. can treat Canadian capital as disposable when U.S. domestic politics flips.

3) Extraterritorial reach into Canadians’ private financial lives

FATCA and related information-sharing arrangements are widely experienced as a sovereignty irritant (and have been litigated in Canada). The Supreme Court of Canada ultimately declined to hear a constitutional challenge in 2023. (STEP)

Takeaway: the U.S. often assumes its laws get to follow people across borders.

4) A surveillance state that had to be restrained after the fact

Bulk telephone metadata collection under Patriot Act authorities became politically toxic and was later reformed/ended under the USA Freedom Act’s structure. (Default)

Takeaway: democracies can drift into overreach; the difference is that overreach can become a scandal, a law change, and a court fight.

5) The post-9/11 stain: indefinite detention and coercive interrogation

Guantánamo’s long-running controversy and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s reporting on the CIA program remain enduring examples of U.S. moral failure. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

Takeaway: the U.S. is capable of serious rights abuses—then also capable of documenting them publicly, litigating them, and partially reversing course.

Five things the People’s Republic of China does that are categorically different

1) Mass rights violations against Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang

The UN human rights office assessed serious human rights concerns in Xinjiang and noted that the scale of certain detention practices may constitute international crimes, including crimes against humanity. Canada has publicly echoed those concerns in multilateral statements. (OHCHR)

Takeaway: this is not “policy disagreement.” It’s a regime-scale human rights problem.

2) Hong Kong: the model of “one country, one party”

The ongoing use of the national security framework to prosecute prominent pro-democracy figures is a live, observable indicator of how Beijing treats dissent when it has full jurisdiction. (Reuters)

Takeaway: when Beijing says “stability,” it means obedience.

3) Foreign interference and transnational pressure tactics

Canadian public safety materials and parliamentary reporting describe investigations into transnational repression activity and concerns around “overseas police stations” and foreign influence. (Public Safety Canada)

Takeaway: the Chinese state’s threat model can extend into diaspora communities abroad.

4) Systematic acquisition—licit and illicit—of sensitive technology and IP

The U.S. intelligence community’s public threat assessment explicitly describes China’s efforts to accelerate S&T progress through licit and illicit means, including IP acquisition/theft and cyber operations. (Director of National Intelligence)

Takeaway: your “market partner” may also be running an extraction strategy against your innovation base.

5) Environmental and maritime predation at scale

China remains a dominant player in coal buildout even while expanding renewables, a dual-track strategy with global climate implications. (Financial Times)

On the oceans, multiple research and advocacy reports emphasize the size and global footprint of China’s distant-water fishing and associated IUU concerns. (Brookings)

Takeaway: when the state backs extraction, the externalities get exported.

Compare and contrast: the difference is accountability

If you read those lists and conclude “both sides are bad,” you’ve missed the key variable.

The U.S. does bad things in a system with adversarial leak paths:

investigative journalism, courts, opposition parties, congressional reports, and leadership turnover. That doesn’t prevent abuses. It does make abuses contestable—and sometimes reversible. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

China does bad things in a system designed to prevent contestation:

one-party rule, censorship, legal instruments aimed at “subversion,” and a governance style that treats independent scrutiny as hostile action. The problem isn’t “China is foreign.” The problem is that the regime’s incentives run against transparency by design. (Reuters)

So when someone says, “Maybe we should pivot away from the Americans,” the adult response is:

- Yes, diversify.

- No, don’t pretend dependency on an authoritarian state is merely a swap of suppliers.

A quick media-literacy rule for your feed

If a post uses a checklist like “America did X, therefore China is fine,” it’s usually laundering a conclusion.

A better frame is risk profile:

- In a democracy, policy risk is high but visible—and the country can change its mind in public.

- In a one-party state, policy risk is lower until it isn’t—and then you discover the rules were never meant to protect you.

Canada can do business with anyone. But it should not confuse trade with trust, or frustration with Washington with safety in Beijing.

If Canada wants autonomy, the answer isn’t romanticizing China. It’s building a broader portfolio across countries where the rule of law is not a slogan in a press release.

References

- Canada–China trade reset (EV tariffs/canola): Reuters; Guardian. (Reuters)

- U.S. criticism of Canada opening to Chinese EVs: Reuters. (Reuters)

- U.S. tariffs/lumber disputes: Global Affairs Canada; Reuters. (Global Affairs Canada)

- Keystone XL termination: TC Energy; Government of Alberta. (TC Energy)

- FATCA Canadian challenge result: STEP (re Supreme Court dismissal). (STEP)

- USA Freedom Act / end of bulk metadata: Lawfare; Just Security. (Default)

- CIA detention/interrogation report: U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee report PDF. (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence)

- Guantánamo context: Reuters; Amnesty. (Reuters)

- Xinjiang assessment: OHCHR report + Canada multilateral statement. (OHCHR)

- Hong Kong NSL crackdown example: Reuters (Jimmy Lai). (Reuters)

- Transnational repression / overseas police station concerns: Public Safety Canada; House of Commons report PDF. (Public Safety Canada)

- China tech acquisition / IP theft framing: ODNI Annual Threat Assessment PDF. (Director of National Intelligence)

- Coal buildout: Financial Times; Reuters analysis. (Financial Times)

- Distant-water fishing footprint / IUU concerns: Brookings; EJF; Oceana. (Brookings)

The West keeps making a category error. It treats Islam as “a religion” in the narrow civic sense modern liberal societies usually mean: private belief, voluntary worship, and a clean separation between pulpit and state.

Islam can be lived that way. Many Muslims do live that way. But Islam, as a tradition, also carries a developed legal–political vocabulary: a picture of how authority, law, community, and public order ought to be arranged. That does not make Muslims suspect. It makes Western assumptions incomplete. A liberal society can only defend what it can name.

A faith that has historically included law

In the classical Islamic tradition, sharia is not only “spiritual guidance.” It is commonly described as governing interpersonal conduct and regulating ritual practice, and in some countries it is applied as governing law or in specific legal domains. (Judiciaries Worldwide) That matters because the modern West is built on a particular settlement: religious freedom inside a civic order that does not belong to any religion.

The relationship between religion and governance in Islamic history also does not map neatly onto the European story of Church versus state. Even critics of the simplistic slogan that Islam “fuses religion and politics” concede a real point beneath it: Muslim thinkers draw distinctions between din (religion) and dawla (state), but the domains and their interrelations do not mirror the European pattern. (MERIP)

So when Western elites insist, “Islam is just a religion,” they are not being tolerant. They are being imprecise. And imprecision is how liberal societies lose arguments before they begin.

The distinction that matters: Islam and Islamism

Precision starts by separating two things that get blurred, sometimes by ignorance, sometimes by strategy:

- Islam: a religion with immense internal diversity, spiritual, legal, philosophical, cultural.

- Islamism (political Islam): a broad set of political ideologies that draw on Islamic symbols and traditions in pursuit of sociopolitical objectives. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A devout Muslim can reject Islamism. A culturally Muslim person can reject Islamism. A believer can treat sharia as personal ethics while rejecting its coercive imposition in a pluralist state. Islamic sources themselves contain the frequently cited line: “Let there be no compulsion in religion.” (Quran.com)

But it is also true that in many parts of the world, substantial numbers of Muslims express support for making sharia “the official law of the land.” (Pew Research Center) That doesn’t prove anything about your Muslim neighbour in Edmonton. It does establish something narrower and important: the political question is not imaginary. It is not a fringe invention.

The engine: infallible doctrine, universal horizon

The political question is whether a movement treats its doctrine as a governing blueprint, one that must eventually become public authority. That is what makes Islamism different from ordinary piety: it is not satisfied with private devotion or voluntary community. It wants law, policy, and state power aligned to a sacred ideal.

If you want a useful analogue for how Islamism works, look at Marxism. Not in theology, mechanics. The doctrine is treated as infallible, so failure can’t belong to the doctrine; it must belong to the people, the impurities, or the enemies. That logic produces a predictable politics: dissent becomes not an alternative view but a problem to be managed, re-educated, or removed.

From there, the “universal” impulse makes sense. This is not always military conquest talk. More often it is a civilizational horizon: the expectation that Islam should be socially and politically ascendant, with public authority aligned to that vision. Classical Islamic political vocabulary has long included categories describing the realm where Islam has “ascendance,” historically paired with an external realm. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A liberal society can coexist with any faith. It cannot coexist with a program that treats liberal pluralism as a temporary obstacle to be overcome.

What the West keeps getting wrong

Western discourse often collapses three claims into one muddy accusation:

- “Muslims are dangerous.” False, unfair, and morally corrosive.

- “Islam has a legal–political tradition.” True, and visible in texts, history, and institutions. (Judiciaries Worldwide)

- “Islamism is a modern political project that can conflict with liberal norms.” True, and increasingly relevant. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

If claims (2) and (3) are denied out of fear of sounding like (1), the result is not compassion. It is blindness. And blindness is not a strategy.

What a liberal society should do

This does not require panic. It requires clarity.

First, speak precisely. Say “Islamism” when you mean political ideology. Say “Islam” when you mean the religion broadly. Don’t use a sweeping civilizational label to do the work of a specific critique.

Second, draw the civic line cleanly: the liberal state is not negotiable. Freedom of worship is protected. Violence and harassment are punished. Attempts to import coercive religious governance into public law are rejected.

Third, stop outsourcing integration to slogans. Liberalism is not a magic solvent. It is a culture of habits, rights, obligations, and red lines that must be taught and applied evenly.

Fourth, refuse collective guilt. Defend liberal norms without treating ordinary Muslims as a fifth column. A society can oppose an illiberal political project while still welcoming neighbours who want to live in peace.

Here is the honesty sentence: if political Islam is largely marginal in Western societies, with negligible institutional influence and no meaningful appetite for parallel authority, the urgency of this argument drops. If, instead, organized efforts continue to carve out exemptions from liberal norms, to pressure institutions into censorship, or to substitute religious authority for civic law, the urgency rises.

The West doesn’t need a religious war. It needs vocabulary. It needs the courage to name ideological ambition without demonizing human beings. And it needs to remember that liberalism is not the default state of humanity. It is a fragile achievement that survives only when people are willing to defend it

References

- Federal Judicial Center, “Islamic Law and Legal Systems” (overview of sharia as governing interpersonal conduct/ritual practice; sometimes governing law). (Judiciaries Worldwide)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Islamism” (definition as political ideologies pursuing sociopolitical objectives using Islamic symbols/traditions). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Pew Research Center, The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society (overview and chapter on beliefs about sharia; questionnaire language on making sharia official law). (Pew Research Center)

- MERIP, “What is Political Islam?” (discussion of din/dawla and why European categories don’t map neatly). (MERIP)

- MERIP, “Islamist Notions of Democracy” (notes the common modern formulation of “religion and state” and its relationship to secularism debates). (MERIP)

- Qur’an 2:256 (“no compulsion in religion”) and Ibn Kathir tafsir page commonly cited in discussion. (Quran.com)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Dār al-Islām” (political-ideological category describing the realm where Islam has ascendance, traditionally paired with an external realm). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Your opinions…