You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘History’ category.

The last veterans of the Great War departed this world decades ago; those who endured the trenches and bombardments of the Second World War now number fewer than a thousand, most in their late nineties or beyond. With them vanishes the final tether of direct witness to the twentieth century’s cataclysms. What fades is not merely a generation but a form of moral authority — the living memory that once stood before us in uniform and silence. We have reached a civilizational inflection point: the moment when history ceases to be personal recollection and becomes curated narrative, vulnerable to distortion, neglect, or deliberate revision.

This transition demands vigilance. Memory, once embodied in a stooped figure wearing faded medals, could command reverence simply by existing. Now it resides in archives, textbooks, and the contested arena of public commemoration. The risk is not that the past will vanish entirely — curiosity and conscience ensure fragments endure. The greater peril is that it will be instrumentalised: stripped of complexity and pressed into service for transient ideological projects. A battle becomes a hashtag, a sacrifice a soundbite, a hard-won lesson a slogan detached from the blood that purchased it.

Edmund Burke reminded us that society is a partnership not only among the living, but between the living, the dead, and those yet unborn. This compact imposes obligations. We inherit institutions, norms, and liberties refined through centuries of trial, error, and atonement. To treat them as disposable because their origins lie beyond living memory is to saw off the branch on which we sit. The trenches of the Somme, the beaches of Normandy, the frozen forests of the Ardennes—these were not abstractions of geopolitics but crucibles in which the consequences of appeasement, militarised grievance, and contempt for constitutional restraint were written in blood.

The lesson is not that war is always avoidable; history disproves such sentimentalism. It is that certain patterns recur with lethal predictability when prudence is discarded. The erosion of intermediary institutions, the inflation of executive power, the substitution of mass emotion for deliberation—these were the preconditions that turned stable nations into abattoirs. To recognise them requires neither nostalgia nor ancestor worship, only the intellectual honesty to trace cause and effect across generations.

Conserving society in the Burkean sense is therefore active, not passive. It means cultivating the habits that sustain ordered liberty: deference to proven custom tempered by principled reform; respect for the diffused experience of the many rather than the concentrated will of the few; and humility before the limits of any single generation’s wisdom. Remembrance Day, properly observed, is not a requiem for the dead but a summons to the living. It reminds us that the peace we enjoy is borrowed, not owned — and that the interest payments come due in vigilance, discernment, and the quiet courage to defend what has been painfully built.

As the century that began in Sarajevo and ended in Sarajevo’s shadow recedes from living memory, the obligation deepens. We must read the dispatches, study the treaties, weigh the speeches, and above all resist the temptation to flatten the past into morality plays that flatter the present. Only thus do we honour the fallen: not with poppies alone, but with societies sturdy enough to vindicate their sacrifice.

(TL;DR) Eric Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics remains one of the clearest guides to our modern disorder. It teaches that when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void—and history descends into Gnostic fantasy. Voegelin’s remedy is not new revolution but ancient remembrance: the recovery of the soul’s openness to reality.

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) was an Austrian-American political philosopher who sought to diagnose the spiritual derangements of modernity. In his 1952 classic The New Science of Politics—first delivered as the Walgreen Lectures at the University of Chicago—Voegelin proposed that politics cannot be understood as a merely empirical or procedural science. Power, institutions, and law arise from a deeper spiritual ground: humanity’s participation in transcendent order. When societies lose awareness of that participation, they fall into ideological dreams that promise salvation through human effort alone. The book is therefore both a critique of modernity and a call to recover the classical and Christian understanding of political reality (Voegelin 1952, 1–26).

1. The Loss of Representational Truth

Every stable society, Voegelin argued, “represents” its members within a larger order of being. In ancient civilizations and medieval Christendom, political authority symbolized this participation through myth, ritual, and law that acknowledged a reality beyond human control. The ruler was not a god but a mediator between the temporal and the eternal.

Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the monk Joachim of Fiore reimagined history as a self-unfolding divine drama in which humanity itself would bring about the final age of perfection. With this shift, Western consciousness began to “immanentize the eschaton”—to relocate ultimate meaning inside history rather than in its transcendent source. Out of this inversion grew the modern ideologies of progress (Comte, Hegel), revolution (Marx), and race (National Socialism), each promising earthly redemption through planning and will (Voegelin 1952, 107–132).

For Voegelin, the loss of representational truth meant that governments no longer reflected humanity’s place in divine order but instead projected utopian images of what they wished reality to be. Politics ceased to be the articulation of truth and became the engineering of salvation.

2. Gnosticism as the Modern Disease

Voegelin identified the inner structure of these movements as Gnostic. Ancient Gnostics sought hidden knowledge that would liberate the soul from an evil world; their modern successors, he said, sought knowledge that would liberate humanity from history itself. “The essence of modernity,” Voegelin wrote, “is the growth of Gnostic speculation” (1952, 166).

He listed six recurrent traits of the Gnostic attitude:

- Dissatisfaction with the world as it is.

- Conviction that its evils are remediable.

- Belief in salvation through human action.

- Assumption that history follows a knowable course.

- Faith in a vanguard who possess the saving knowledge.

- Readiness to use coercion to realize the dream.

From medieval millenarian sects to twentieth-century totalitarian states, these traits form a single continuum of spiritual rebellion: the attempt to perfect existence by abolishing its limits.

3. The Open Soul and the Pathologies of Closure

Against the Gnostic impulse stands the open soul—the philosophical disposition that accepts the “metaxy,” or the in-between nature of human existence. We live neither wholly in transcendence nor wholly in immanence, but within the tension between them. The philosopher’s task is not to resolve that tension through fantasy or reduction but to dwell within it in faith and reason.

Political science, therefore, must be noetic—concerned with insight into the structure of reality—not merely empirical. A society’s symbols, institutions, and laws can be judged by how faithfully they articulate humanity’s participation in divine order. Disorder, Voegelin warned, begins not with bad policy but with pneumopathology—a sickness of the spirit that refuses reality’s truth. “The order of history,” he wrote, “emerges from the history of order in the soul.”

Empirical data can measure economic growth or electoral results, but it cannot measure spiritual health. That requires awareness of being itself.

4. Liberalism’s Vulnerability and the Way of Recovery

Voegelin saw liberal democracies as historically successful yet spiritually precarious. By reducing political order to procedural legitimacy and rights management, liberalism risks drifting into the nihilism it opposes. When public life forgets its transcendent foundation, freedom degenerates into relativism, and pluralism becomes mere fragmentation.

Still, Voegelin’s outlook was not despairing. His proposed remedy was anamnesis—the recollective recovery of forgotten truth. This is not nostalgia but awakening: the rediscovery that human beings are participants in an order they did not create and cannot abolish. The recovery of the classic (Platonic-Aristotelian) and Christian understanding of existence offers the only durable antidote to ideological apocalypse (Voegelin 1952, 165–190).

To “keep open the soul,” as Voegelin put it, is to resist every movement that promises paradise through force or theory. The alternative is the descent into spiritual closure—an ever-recurring temptation of modernity.

5. Contemporary Resonance

Voegelin’s analysis remains uncannily prescient. Today’s ideological battles—whether framed around identity, technology, or climate—often echo the same Gnostic pattern: discontent with the world as it is, belief that perfection lies just one policy or re-education campaign away, and impatience with reality’s resistance. The post-modern conviction that truth is socially constructed continues the old dream of remaking existence through will and language.

Voegelin’s warning cuts through our century as clearly as it did the last: when politics replaces truth with narrative and transcendence with activism, society repeats the ancient heresy in secular form. The cure, as ever, is humility before what is—the recognition that order is discovered, not invented.

References

Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Glenn. 2003. Transcendence and History: The Search for Ultimacy from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Sandoz, Ellis. 1981. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glossary of Key Terms

Anamnesis – Recollective recovery of forgotten truth about being.

Gnosticism – Revolt against the tension of existence through claims to saving knowledge that masters reality.

Immanentize the eschaton – To locate final meaning and salvation within history rather than beyond it.

Metaxy – The “in-between” condition of human existence, suspended between immanence and transcendence.

Noetic – Pertaining to intellectual or spiritual insight into reality’s order.

Pneumopathology – Spiritual sickness of the soul that closes itself to transcendent reality.

Representation – The symbolic and political articulation of a society’s participation in transcendent order.

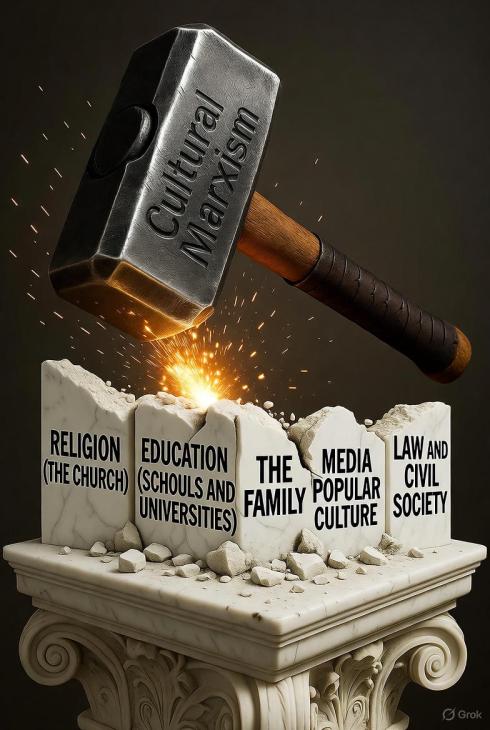

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist imprisoned by Mussolini, changed political strategy forever by shifting revolution from the factory floor to the realm of culture. His concept of cultural hegemony—the quiet capture of schools, media, and moral institutions—remains the blueprint for the modern Left’s “long march through the institutions.” Understanding him is key to understanding how ideology became the new battlefield of Western democracy.

Why the twentieth century’s most subversive Marxist remains essential to understanding our political moment.

Antonio Gramsci has become a ghostly presence in today’s politics—invoked by both left and right, praised as a prophet of cultural liberation and blamed as the architect of “Cultural Marxism.” Yet few who use his name understand the subtlety of what he actually proposed. Gramsci, an Italian communist jailed by Mussolini from 1926 until his death in 1937, recognized that Western societies could not be overthrown by economic revolution alone. The real battleground, he argued, lay in the culture—in the stories a society tells itself about who it is, what it values, and what it considers “common sense.”

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci dissected how ruling elites maintain power not only through economic control or state coercion but through the manufacture of consent—what he called cultural hegemony. When the public unconsciously accepts elite norms as their own, open coercion becomes unnecessary. The power structure endures because people cannot easily imagine alternatives.

From Marx to Culture: The Pivot that Changed the Left

This insight quietly revolutionized the Marxist project. Where Marx saw power rooted primarily in economics, Gramsci saw it reproduced through education, religion, art, the press, and civic institutions—what he called “civil society.” If these were the true engines of social continuity, then a revolutionary movement must capture them before capturing the state. The task, therefore, was not simply to seize the means of production but to seize the means of persuasion.

That shift—from factory to faculty, from economics to ideology—birthed what would later be called Cultural Marxism. It gave rise to the post-war New Left and, through the Frankfurt School, to a range of “critical” theories that continue to shape university life and activist politics. Power was no longer viewed as residing primarily in class relations but in language, identity, and culture. Gramsci’s “war of position”—a slow, patient infiltration of cultural institutions—became the model.

The Five Fronts of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci never offered a neat checklist, but his writings identify five interlocking domains where the battle for hegemony is fought—and where Western institutions have since seen the most visible transformations:

- Religion and Moral Order – For centuries, the Church anchored Western moral consensus. Gramsci saw it as the spiritual foundation of bourgeois power. Undermining or secularizing that foundation was essential to remaking moral consciousness.

- Education and the Intelligentsia – Schools and universities, he observed, do not merely transmit knowledge; they reproduce ideology. Control the curriculum, train the teachers, shape the young—and you shape tomorrow’s society.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, cinema, art, and now digital media cultivate public sentiment. Altering how people speak, joke, and imagine themselves can shift the moral vocabulary of an entire civilization.

- Civil Society and Voluntary Institutions – Clubs, unions, NGOs, and advocacy groups form the connective tissue between individuals and the state. They generate the “organic intellectuals” who articulate a new worldview and lend legitimacy to political change.

- Law, Politics, and the Administrative State – Finally, cultural transformation must be consolidated through legal norms, policy, and bureaucratic language, ensuring that the new values become institutional reflexes rather than contested ideas.

Each domain is a theatre in the long “war of position.” The aim is not an immediate coup but the gradual erosion of inherited norms until the revolutionary outlook feels like common sense.

Why Gramsci Still Matters

Gramsci’s legacy is paradoxical. His analysis was intellectually brilliant—but by detaching revolution from economics and anchoring it in culture, he supplied future radicals with a strategy for subverting liberal democracy from within. The New Left of the 1960s and its academic descendants adopted his playbook, translating class struggle into struggles over race, gender, language, and identity. In this sense, Gramsci stands as both the diagnostician and the progenitor of our current ideological turbulence.

For those tracing the lineage of today’s cultural battles, reading Gramsci is essential. His theory of hegemony explains why institutions that once served as stabilizing forces—universities, churches, professional guilds, and even the arts—have become arenas of moral and political conflict. It also clarifies why dissenters within those institutions are treated not as intellectual adversaries but as heretics.

Reading the Intellectual Landscape

This essay continues the Learning the Lay of the Land series here at Dead Wild Roses, which maps the ideas that reshaped Western political thought:

- Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism — how ideological certainty breeds totalitarian temptation.

- Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and the Birth of Cultural Hegemony — a deep dive into his original ideas.

- Orwell’s Politics and the English Language — how linguistic corruption becomes political control.

- Mill’s On Liberty — a defence of intellectual freedom against the new orthodoxy.

Together they outline the terrain of our ideological crisis: from Arendt’s warning about totalitarian habits of mind, through Gramsci’s theory of cultural capture, to Orwell’s exposure of linguistic manipulation and Mill’s insistence on free thought.

Closing Reflection

Gramsci’s insight—that the health of a society depends on who defines its common sense—remains the axis on which our modern conflicts turn. Understanding his ideas is not an act of homage, but of inoculation. To preserve a free and open civilization, one must know precisely how it can be subverted—and Gramsci told us, in meticulous detail, how that can be done.

Primary Sources

Gramsci, Antonio. *Selections from the Prison Notebooks*. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971. (Core text for concepts of cultural hegemony, war of position, civil society, and organic intellectuals; selections from Notebooks 1–29, written 1929–1935.)

Secondary Sources

Arendt, Hannah. *The Origins of Totalitarianism*. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. (Referenced in series context for ideological escalation into totalitarianism.)

Mill, John Stuart. *On Liberty*. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859. (Referenced in series context as counterpoint to hegemonic orthodoxy.)

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” *Horizon* 13, no. 76 (April 1946): 252–265. (Referenced in series context for linguistic mechanisms of ideological control.)

Additional Contextual Works

Jay, Martin. *The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950*. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973. (Provides linkage between Gramsci’s cultural pivot and post-war Critical Theory.)

Rudd, Mark. “The Long March Through the Institutions: A Memoir of the New Left.” In *The Sixties Without Apology*, edited by Sohnya Sayres et al., 201–218. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. (Illustrates practical adoption of Gramscian strategy in 1960s activism.)

Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) was an Italian Marxist philosopher and revolutionary who reimagined the battlefield of socialism. Where Marx envisioned revolution through economic crisis and class struggle, Gramsci located the real battleground in culture—in the stories, moral codes, and institutions that shape how people perceive reality. His insight reshaped leftist strategy throughout the 20th century and remains the foundation of what has come to be known, often critically, as Cultural Marxism.

Gramsci’s imprisonment by Mussolini between 1926 and 1937 produced the Prison Notebooks, a collection of reflections on history, education, religion, and power that would change Marxism forever. Rather than calling for immediate insurrection, Gramsci argued that Western societies were held together not merely by force, but by consent—the consent of people whose minds had been molded by dominant cultural institutions. To overthrow capitalism, the revolution would first have to capture culture.

The Concept of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci coined the term “cultural hegemony” to describe the way ruling classes maintain control by shaping what society considers “common sense.” Schools, churches, media, literature, and even family life all help reproduce the values that support the existing order. To Gramsci, the working class could never achieve political power until it produced a counter-hegemony—a rival moral and intellectual framework capable of displacing the dominant bourgeois worldview.

This insight was transformative. It shifted Marxist focus from economic structures to cultural superstructures—from factories to universities, from political parties to publishing houses. The revolution would be waged not only with rifles and manifestos, but with textbooks, art, and language itself.

The Five Pillars of Western Hegemony

Gramsci identified several key arenas where cultural hegemony is maintained and where revolutionary transformation must occur. Though he never formally listed “five areas,” his writings consistently emphasize these interlocking domains as the loci of bourgeois cultural power:

- Religion (The Church) – The Church was, for Gramsci, the moral anchor of Western civilization. Its authority shaped notions of duty, sin, and redemption. For a new socialist order to take root, Marxists would need to displace religious authority with secular, materialist moral systems.

- Education (Schools and Universities) – Schools reproduce social hierarchies by transmitting the ideology of the ruling class. Gramsci saw education as the most potent tool for cultivating a new “collective will.” Intellectuals, teachers, and professors were to become “organic intellectuals” of the working class—agents of counter-hegemony.

- The Family – As the smallest unit of moral and cultural reproduction, the family passes on norms of obedience, gender roles, and private property. Gramsci argued that socialist transformation required reconfiguring family life to reflect collective rather than patriarchal or bourgeois values.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, radio, and entertainment function as instruments of social consent. Control over communication channels would allow the revolutionary movement to redefine reality itself—to make socialist ideas seem natural and just.

- Law and Civil Society – Beyond the coercive power of the state lies civil society: courts, voluntary associations, clubs, and unions. These mediate between individuals and the state, embedding ruling-class ideology in everyday life. The Left’s long march through these institutions, later theorized by figures like Rudi Dutschke, stems directly from Gramsci’s idea of building a counter-hegemonic presence within civil society.

From Class War to Culture War

Gramsci’s influence has proven far greater than his lifetime achievements would suggest. His Prison Notebooks became a cornerstone for postwar Marxist thinkers of the Frankfurt School—Herbert Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, and others—who expanded his ideas into critical theory. Together, they seeded what would evolve into the New Left, identity-based activism, and much of today’s academic “social justice” thought.

While critics argue that Gramsci’s ideas have fostered divisive cultural politics, even they concede his enduring genius: he saw that culture precedes politics. Whoever controls a society’s moral vocabulary ultimately controls its laws, institutions, and collective imagination.

Why Gramsci Matters Today

Understanding Gramsci is essential to understanding the modern cultural landscape. His legacy explains why ideological movements increasingly contest meanings—of gender, race, language, and history—rather than material production. The “long march through the institutions” that Gramsci inspired is visible across Western education, media, and bureaucracies.

Whether one views this as intellectual renewal or cultural subversion, Gramsci’s insight endures: power begins in the mind before it manifests in law.

References

- Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971.

- Buttigieg, Joseph A. Antonio Gramsci: Prison Notebooks, Vols. I–III. Columbia University Press, 1992–2007.

- Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. University of California Press, 2002.

- Dutschke, Rudi. “The Long March Through the Institutions.” (Speech, 1967).

- Jay, Martin. The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950. University of California Press, 1973.

I’ve summarized the article here.

In challenging the prevailing narrative of unmitigated harm in Canada’s residential schools, Michelle Stirling scrutinizes Phyllis Webstad’s story, the inspiration behind Orange Shirt Day. Webstad boarded at St. Joseph’s in 1973, a facility under federal oversight where she attended public school alongside local children, not a cloistered religious institution. Stirling points out the absence of Catholic nuns in daily operations by that time, with Indigenous staff predominant, and questions the portrayal of familial abandonment on the Dog Creek Reserve amid documented violence, suggesting her placement served as a safeguard rather than an act of cultural erasure.

Vivian Ketchum’s recollection of being removed at age five to the Presbyterian-run Cecilia Jeffrey school is similarly contextualized as a welfare intervention, particularly against the backdrop of tuberculosis ravaging her community, which left her with lung scars. Stirling dismantles media distortions, such as those in “The Secret Path,” which erroneously inject Catholic elements into a Presbyterian setting, while citing Robert MacBain’s compilation of affirmative student letters that refute widespread abuse claims and highlight the school’s role as a refuge from dire home conditions.

Stirling ultimately cautions against the pitfalls of relying on childhood memories in legal compensation processes, where leading questions can shape recollections, and contrasts dominant tales with positive accounts like Lena Paul’s depiction of the school as a haven from familial turmoil. By exposing fabrications in works like the “Sugarcane” documentary, the article advocates for a balanced historical lens that prioritizes verifiable facts over emotive victimhood, fostering genuine reconciliation free from manipulated animosity.

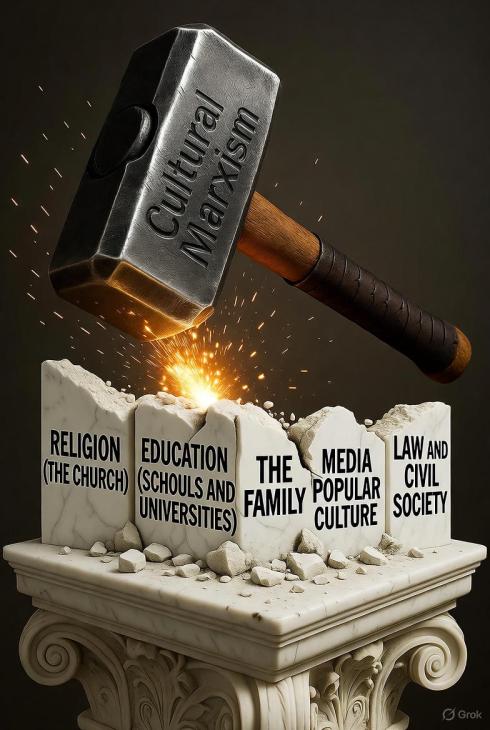

In an age that demands shame from the West, Douglas Murray deploys the ultimate counterstrike:

“I don’t especially think of myself as being white and don’t particularly want to be cornered into thinking in such terms. But if you are going to corner me, then let me give you an answer to the best of my ability.

“The good things about being white include being born into a tradition that has given the world a disproportionate number, if not most, of the things that the world currently benefits from. The list of things that white people have done may include many bad things, as with all peoples. But the good things are not small in number. They include almost every medical advancement that the world now enjoys. They include almost every scientific advancement that the world now benefits from. No meaningful breakthrough in either of these areas has come for many centuries from anywhere in Africa or from any Native American tribe. No First Nation wisdom ever delivered a vaccine or a cure for cancer.

“White people founded most of the world’s oldest and longest-established educational institutions. They led the world in the invention and promotion of the written word. Almost alone among any peoples it was white people who—for good and for ill—took an interest in other cultures beyond their own, and not only learned from these cultures but revived some of them. Indeed, they have taken such an interest in other peoples that they have searched for lost and dead civilizations as well as living ones to understand what these lost peoples did, in an attempt to learn what they knew. This is not the case with most other peoples. No Aboriginal tribe helped make any advance in understanding the lost languages of the Indian subcontinent, Babylon, or ancient Egypt. The curiosity appears to have gone almost entirely one way. In historical terms, it seems to be as unusual as the self-reflection, the self-criticism, and indeed the search for self-improvement that marks out Western culture.

“White Western peoples happen to have also developed all the world’s most successful means of commerce, including the free flow of capital. This system of free market capitalism has lifted more than one billion people out of extreme poverty just in the twenty-first century thus far. It did not originate in Africa or China, although people in those places benefited from it. It originated in the West. So did numerous other things that make the lives of people around the world immeasurably better.

“It is Western people who developed the principle of representative government, of the people, by the people, for the people. It is the Western world that developed the principles and practice of political liberty, of freedom of thought and conscience, of freedom of speech and expression. It evolved the principles of what we now call ‘civil rights,’ rights that do not exist in much of the world, whether their peoples yearn for them or not. They were developed and are sustained in the West, which though it may often fail in its aspirations, nevertheless tends to them.

“All this is before you even get onto the cultural achievements that the West has gifted the world. The Mathura sculptures excavated at Jamalpur Tila are works of exceptional refinement, but no sculptor ever surpassed Bernini or Michelangelo. Baghdad in the eighth century produced scholars of note, but no one ever produced another Leonardo da Vinci. There have been artistic flourishings around the world, but none so intense or productive as that which emerged around just a few square miles of Florence from the fourteenth century onward. Of course, there have been great music and culture produced from many civilizations, but it is the music of the West as well as its philosophy, art, literature, poetry, and drama that have reached such heights that the world wants to participate in them. Outside China, Chinese culture is a matter for scholars and aficionados of Chinese culture. Whereas the culture created by white people in the West belongs to the world, and a disproportionate swath of the world wants to be a part of it.

“When you ask what the West has produced, I am reminded of the groups of professors assigned to agree on what should be sent in a space pod into orbit in outer space to be discovered by another race, if any such there be. When it came to agreeing on what one musical piece might be sent to represent that part of human accomplishment one of the professors said, ‘Well, obviously, it will be Bach’s Mass in B Minor.’ ‘No,’ averred another. ‘To send the B Minor Mass would look like showing off.’ To talk about the history of Western accomplishments is to be put at great risk of showing off. Do we stay just with buildings, or cities, or laws, or great men and women? How do we restrict the list that we put up as a preliminary offer?

“The migrant ships across the Mediterranean go only in one direction—north. The people-smuggling gangs’ boats do not—halfway across the Mediterranean—meet white Europeans heading south, desperate to escape France, Spain, or Italy in order to enjoy the freedoms and opportunities of Africa. No significant number of people wishes to participate in life among the tribes of Africa or the Middle East. There is no mass movement of people wishing to live with the social norms of the Aboriginals or assimilate into the lifestyle of the Inuit, whether those groups would allow them in or not. Despite everything that is said against it, America is still the world’s number one destination for migrants worldwide. And the next most desirable countries for people wanting to move are Canada, Germany, France, Australia, and the United Kingdom. The West must have done something right for this to be the case.

“So if you ask me what is good about being white, what white people have brought to the world, or what white people might be proud of, this might constitute the mere beginnings of a list of accomplishments from which to start. And while we are at it, one final thing. This culture that it is now so fashionable to deprecate, and which people across the West have been encouraged and incentivized to deprecate, remains the only culture in the world that not only tolerates but encourages such a dialogue against itself. It is the only culture that actually rewards its critics. And there is one final oddity here worth noting. For the countries and cultures about which the worst things are now said are also the only countries demonstrably capable of producing the governing class unlike all of the others.

“It is not possible today for a non-Indian to rise to the top of Indian politics. If a white person moved to Bangladesh, they would not be able to become a cabinet minister. If a white Westerner moved to China, neither they nor the next generation of their family nor the one after that would be able to break through the layers of government and become supreme leader in due course. It is America that has twice elected a black president—the son of a father from Kenya. It is America whose current vice president is the daughter of immigrants from India and Jamaica. It is the cabinet of the United Kingdom that includes the children of immigrants from Kenya, Tanzania, Pakistan, Uganda, and Ghana and an immigrant who was born in India. The cabinets of countries across Africa and Asia do not reciprocate this diversity, but it is no matter. The West is happy to accept the benefits this brings, even if others are not.”

-Douglas Murray from the Conclusion of War on the West.

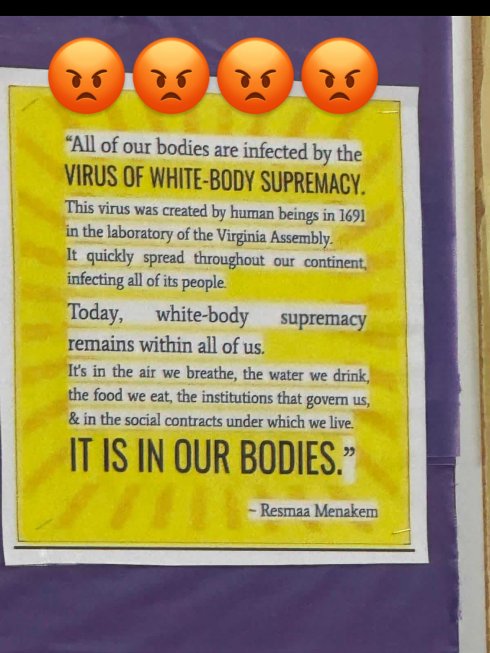

The poster’s quotation from Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands—a work on “somatic abolitionism”—masquerades as profound insight while peddling a corrosive myth: that white supremacy originated as a deliberate “virus” engineered in 1691 by the Virginia Assembly and now lives in every human body like an inescapable plague. This is not scholarship; it is narrative alchemy, transmuting concrete historical injustices into a metaphysical pathology that demands perpetual atonement from those deemed its carriers.

The verifiable record tells a different story. In 1691, the Virginia General Assembly did indeed enact a statute prohibiting interracial marriage and prescribing banishment for violators, declaring such unions “always to be held and accounted odious.” This and earlier laws—like the 1662 act establishing that a child’s enslaved status followed the condition of the mother—were instruments of economic control designed to stabilize a plantation system dependent on enslaved labor. They reflected cruelty and racial hierarchy, but to describe the Assembly as a “laboratory” that “created a virus” is to abandon historical analysis for political mythmaking.

Menakem’s metaphor extends beyond history into biological moralism. He claims the “virus of white-body supremacy” infects all people—Black, white, and otherwise—but insists that “white bodies” were its original vector. In doing so, his language transforms a moral failing into a physical contamination, pathologizing not actions or institutions but entire human beings. This rhetoric does not enlighten; it indicts an entire lineage for ancestral crimes, regardless of individual conscience or conduct.

The psychological consequence is predictable: self-loathing disguised as virtue. By teaching that “white bodies” are inherently supremacist, this ideology demands that people view their very physiology and heritage as polluted. It secularizes the ancient idea of inherited guilt, substituting ritual “somatic abolition” for redemption. The irony is tragic: the same civilization Menakem condemns also produced the philosophical and political revolutions—the Enlightenment, abolitionism, universal rights—that made slavery morally indefensible in the first place.

Finally, the metaphor corrodes civic trust. The Virginia Assembly, for all its failings, was also one of the earliest elected legislatures in the New World. To recast it as a “mad scientist’s lab” birthing a contagion of supremacy is to delegitimize the democratic experiment at its roots, suggesting that all institutions derived from it remain vectors of infection rather than imperfect vessels of self-correction and progress. Such thinking feeds cynicism, not justice, and erodes the moral foundations of the very equality it claims to seek.

Slavery and racial hierarchy were evils of human design, not biological inevitabilities. We honor truth by condemning those evils as moral and political wrongs—without collapsing into the superstition that guilt resides in the body or that redemption requires permanent contrition. The only real contagion here is the idea that identity determines virtue.

References

- Menakem, Resmaa. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

— Source of the “virus of white-body supremacy” metaphor and “laboratory of the Virginia Assembly” phrasing. - Hening, William Waller (ed.). The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619. Vol. 3. New York: R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823.

— Contains the 1662 and 1691 acts (“Act XII” of 1662 and “Act XVI” of 1691) establishing hereditary slavery and banning interracial marriage. - Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1975.

— Authoritative analysis of how race-based slavery evolved in colonial Virginia as a means of stabilizing class hierarchies. - Davis, David Brion. The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1966.

— Foundational work tracing slavery’s intellectual and moral contexts in Western thought. - Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

— Historical survey of the transformation from indentured servitude to race-based chattel slavery. - Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

— Explores the moral and political inheritance of the Virginia Assembly and the paradox of liberty coexisting with slavery. - Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1945.

— Classic defense of open inquiry and individual moral responsibility against collectivist and totalizing ideologies.

Your opinions…