In the first post of this series, we traced the roots of the oppressor/oppressed lens to the Combahee River Collective, Paulo Freire, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, who gave us tools like intersectionality to understand systemic injustice. We also saw how Freire’s focus on class consciousness prioritized ideological awakening over factual learning, setting the stage for a binary moral framework. Today, this lens is everywhere—on X, in workplaces, in classrooms—shaping how we judge right from wrong. But as it’s gone mainstream, it’s often been stretched beyond its original purpose, turning a tool for analysis into a blunt moral weapon. In this post, we’ll explore how thinkers like Judith Butler, Robin DiAngelo, and John McWhorter reveal the lens’s strengths and its modern misuses, showing why it falls short as a universal moral guide.

The Lens in Action: From Insight to Ideology

The oppressor/oppressed lens is powerful because it names systemic harms—like racism, sexism, or classism—that shape daily life. It’s why a Black woman like Maya, from our last post, can use intersectionality to explain her unique workplace barriers. But as the lens has spread, it’s often applied in ways that oversimplify complex realities, fostering division over dialogue. Three thinkers help us unpack this shift: Judith Butler, who shows the fluidity of power; Robin DiAngelo, who mainstreamed the lens but risks coercive moralism; and John McWhorter, who critiques its dogmatic turn.

Judith Butler: Power and Performativity

Judith Butler’s groundbreaking work, particularly Gender Trouble (1990), challenges the idea of fixed identities within the oppressor/oppressed framework. Butler argues that gender is not a static trait but a performance—something we “do” through repeated social acts, shaped by power structures. For example, a woman might feel pressure to act “feminine” to avoid judgment, reinforcing societal norms. This performativity extends to other identities, like race or class, showing how power operates dynamically, not just through rigid categories of oppressor or oppressed.

Butler’s ideas enrich the lens by revealing how oppression is sustained through everyday practices, not just top-down systems. But they also complicate it. If identities are fluid and constructed, the binary of oppressor vs. oppressed can feel too simplistic. For instance, a white woman might face sexism (oppression) while benefiting from racial privilege (oppressor status). Butler’s work suggests that power shifts with context, yet the lens is often applied as a static moral rule, ignoring this nuance. On X, you might see someone labeled “privileged” based on one identity, erasing the complexity Butler highlights.

Robin DiAngelo: Mainstreaming the Lens, Repopularizing Struggle Sessions

Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (2018) brought the oppressor/oppressed lens to a wider audience by framing systemic racism as an everyday reality. She argues that white people, by virtue of their race, uphold oppression through unconscious biases and defensive reactions (like discomfort when discussing racism). Her work popularized the idea that oppression isn’t just overt acts but subtle behaviors—like a white manager overlooking Maya for a promotion without realizing why. By making systemic issues accessible, DiAngelo urged people to examine their role in oppression, a valuable step for many.

But DiAngelo’s approach has serious flaws, particularly in how it’s applied in workshops and trainings. Her methods often resemble modern-day “struggle sessions,” where participants are pressured to publicly confess their moral failings—like admitting to “white privilege” or “unconscious racism”—to prove their commitment to justice. In a typical DiAngelo-inspired DEI session, employees might be asked to share personal biases in front of colleagues, creating a high-stakes environment where refusal risks being labeled “fragile” or complicit. Critics, including John McWhorter, argue this echoes the coercive self-criticism of Maoist struggle sessions, prioritizing performative guilt over genuine learning. By focusing on group identity (e.g., “whiteness”) as inherently oppressive, DiAngelo’s framework reduces people to moral categories, sidelining individual actions or context. This not only alienates participants—imagine a low-income white worker being told to “check their privilege”—but also stifles dialogue, as dissent is framed as denial. Like Freire’s ideological focus, DiAngelo’s lens emphasizes awareness over solutions, turning moral inquiry into a ritual of confession.

John McWhorter: The Dogmatic Turn

John McWhorter, in Woke Racism (2021), takes aim at the lens’s modern misuse, arguing it’s become a performative ideology that stifles progress. He contends that the oppressor/oppressed framework, when applied dogmatically, fosters a “religion-like” moralism where dissent is heresy. For example, on X, a user might be “canceled” for questioning a social justice claim, not because they’re wrong but because they’re seen as defending “oppressor” views. McWhorter argues this shuts down debate and alienates potential allies, like people who support racial justice but disagree with specific tactics.

McWhorter doesn’t dismiss systemic oppression—he acknowledges its reality—but critiques how the lens prioritizes moral purity over solutions. In a workplace, a DEI trainer might focus on calling out “microaggressions” without offering ways to address structural issues, like hiring biases. This echoes Butler’s insight: power is complex and contextual, not a simple binary. McWhorter’s critique shows how the lens, when rigid, becomes less about understanding and more about signaling virtue, amplifying the coercive dynamics DiAngelo’s methods often foster.

Why It Falls Short

Butler, DiAngelo, and McWhorter reveal the oppressor/oppressed lens’s double edge. Butler shows that power and identity are too fluid for a binary framework. DiAngelo’s mainstreaming makes oppression visible but risks coercive moralism, repopularizing struggle session-like practices that prioritize guilt over dialogue. McWhorter warns that dogmatic applications turn the lens into a divisive ideology. Together, they suggest that while the lens can illuminate systemic wrongs, it often fails to navigate the messy, contextual nature of human morality. When it’s used to judge people as “good” or “bad” based on identity—like in viral X posts or rigid DEI programs—it shuts down the very dialogue it once sparked.

What’s Next?

The oppressor/oppressed lens is a vital tool, but its modern applications, from DiAngelo’s struggle sessions to social media pile-ons, show its limits as a moral guide. In the next post, we’ll dig deeper into those limits with insights from bell hooks and Joe L. Kincheloe, exploring how the lens can foster division over solidarity. Then, we’ll propose a more nuanced framework for navigating morality. What are your experiences with this lens in today’s world? Share them in the comments—I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Sources: Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990), Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (2018), John McWhorter’s Woke Racism (2021).

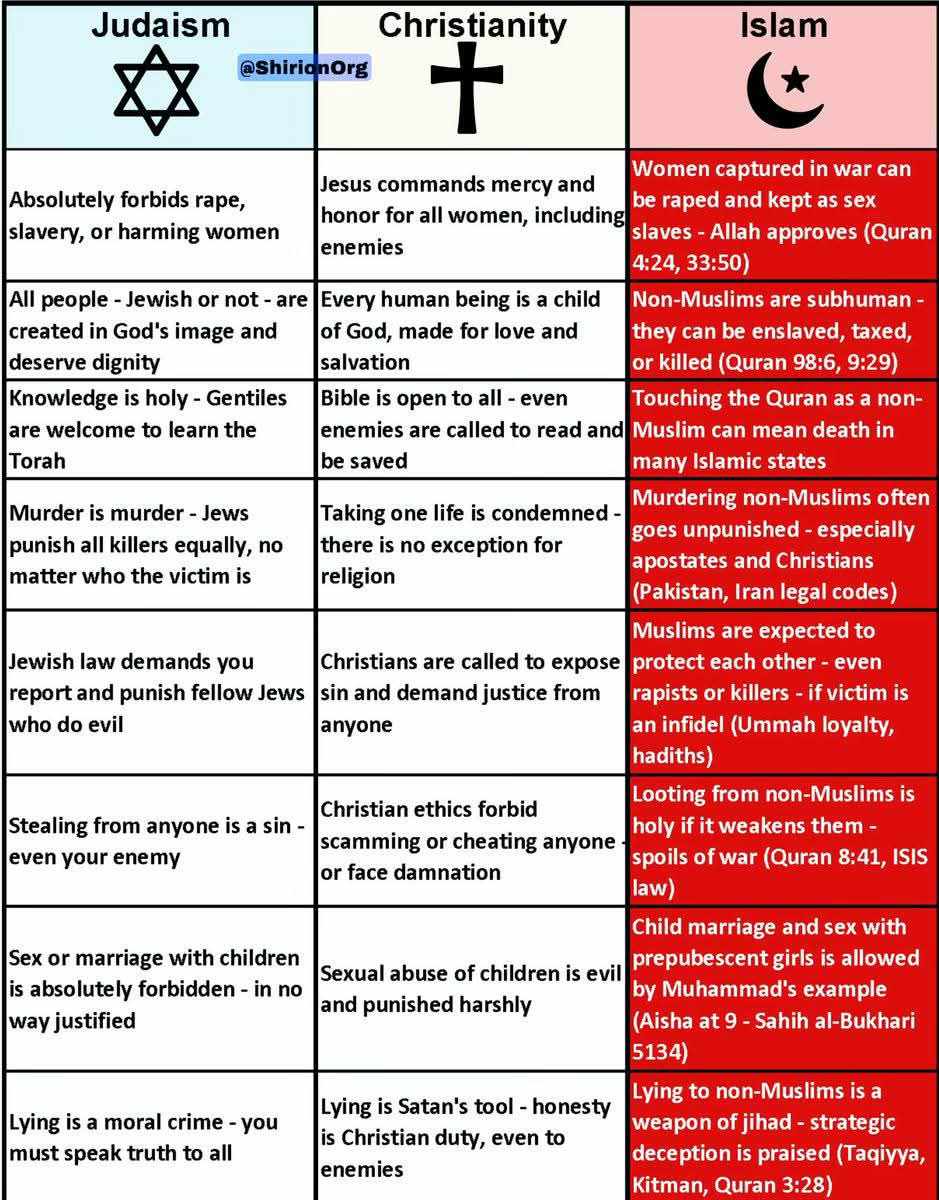

The foundations of classically liberal societies, characterized by individual freedoms, rule of law, and democratic governance, are significantly influenced by Judeo-Christian values that shaped Western civilization. These values, rooted in the ethical and moral frameworks of Judaism and Christianity, provided a philosophical basis for concepts such as human dignity, personal responsibility, and the inherent worth of the individual. While secular ideologies emphasize empirical reasoning, historical evidence suggests that Judeo-Christian principles played a pivotal role in the development of modern liberties. This essay presents the strongest possible arguments for the influence of Judeo-Christian values on contemporary freedoms, ensuring historical accuracy and addressing potential criticisms from an objective perspective.

The foundations of classically liberal societies, characterized by individual freedoms, rule of law, and democratic governance, are significantly influenced by Judeo-Christian values that shaped Western civilization. These values, rooted in the ethical and moral frameworks of Judaism and Christianity, provided a philosophical basis for concepts such as human dignity, personal responsibility, and the inherent worth of the individual. While secular ideologies emphasize empirical reasoning, historical evidence suggests that Judeo-Christian principles played a pivotal role in the development of modern liberties. This essay presents the strongest possible arguments for the influence of Judeo-Christian values on contemporary freedoms, ensuring historical accuracy and addressing potential criticisms from an objective perspective.

Your opinions…