You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Equality’ tag.

We still have far to go as civilization, when half the population is subject to shite like this.

I see and hear this little piece of dudely wisdom far, FAR, too often. It represents such an massive break from reality, and yet this harmful trope continues onward. The usual suspects make their appearances, privilege, misogyny the unexamined life – reasons but not excuses for not being in the know when dealing with the basic issue of should we treat women like human beings. It should be concise answer. It almost never is because there inevitably is that lovely word ‘but’ appended to the answer.

I see and hear this little piece of dudely wisdom far, FAR, too often. It represents such an massive break from reality, and yet this harmful trope continues onward. The usual suspects make their appearances, privilege, misogyny the unexamined life – reasons but not excuses for not being in the know when dealing with the basic issue of should we treat women like human beings. It should be concise answer. It almost never is because there inevitably is that lovely word ‘but’ appended to the answer.

Oh yes, women should be treated as human beings, but this Feminism stuff has gone to far.

Yes, women should be treated like human beings, but why all the hate for men why can’t we all just get along?

Yes, but we’re already equal, so what’s the big deal?

The most basic rule when dealing with oppressed classes of people is – shut up and listen. *You* (privileged while males, for example) do not get make the call on saying when someone is genuinely oppressed or when their oppression is done, or anything to do with what they are experiencing as a member of that particular oppressed category. Get over yourself and realize that your opinion has no magical qualities that make it better than those of others, sure it has been the default in society for ages now, but that is changing slowly and will continue to do so whether you are with the program or not.

Feminism is fighting the good fight attempting to make society a better place for women. Feminism is dealing with the mischaracterizations and stereotypes that hurt women in our society, but the fight is far from over. I may have already posted this video, but I found the extended trailer of Miss-representation on youtube. Thank you Sociological Images.

Listen, reflect and take the time to think about what is being postulated. Enjoy.

I wish I had gotten around to reading this book sooner. It is a great read and takes a great deal of piss out of the arguments (made by our beloved conservative/libertarian friends) for lower taxes and more love for the wealthy. I highly recommend reading it. Check out other reviews here and here. I found a brief summary of what McQuaig talks about in the book:

I wish I had gotten around to reading this book sooner. It is a great read and takes a great deal of piss out of the arguments (made by our beloved conservative/libertarian friends) for lower taxes and more love for the wealthy. I highly recommend reading it. Check out other reviews here and here. I found a brief summary of what McQuaig talks about in the book:

“In the last few decades, the concentration of income in the United States, Britain and Canada has reached levels not seen since the late 1920s. Such extreme income concentration created a dynamic that led to the disastrous Wall Street crash in 2008 – just as it did in 1929. The financial collapse is simply the most striking example of the problems caused by the rise of a new class of billionaires. Their massive fortunes – widely considered benign or even beneficial to society — are actually detrimental to everyone else. The glittering lives of the new super-rich may seem like harmless sources of entertainment. But such concentrated economic power reverberates throughout society, threatening the quality of life and the very functioning of democracy. It’s no accident that the United States claims the most billionaires—but suffers from among the highest rates of infant mortality and crime, the shortest life expectancy, as well as the lowest rates of social mobility and electoral political participation in the developed world. Our society sees itself as a meritocracy. So we tend to regard large fortunes as evidence of great talent or accomplishment. Yet the vast new wealth isn’t due to an increase in talent or effort at the top, but rather to changing social attitudes legitimizing greed and to policy changes made by governments under pressure from the new elite.”

Oh and a quick excerpt from the book taking down the notion of the “self-made” billionaire (p.25 – 28).

“The notion that it should be possible to become a billionaire is rooted in the idea that there are some uniquely talented individuals whose contribution is so great that they deserve to be hugely, fabulously rewarded.

Some billionaires, such as Leo J. Hindery Jr., have made this point themselves. Hindery, whose contribution was to found a cable television sports network, put it this way: “I think there are people, including myself at certain times in my career, who because of their uniqueness warrant whatever the market will bear.” Similarly, Sanford Weill, long a towering figure on Wall Street, is impressed with the contributions of billionaires like himself: “People can look at the last 25 years and say that this is an incredibly unique period of time. We didn’t rely on somebody else to build what we built…”

What is striking in such statements, in addition to the absence of modesty, is the lack of any acknowledgement of the role of society in their good fortune. These men seem unaware of the pervasive role played by society in general (as well as by specific other people) in every aspect of their lives — in nurturing them, shaping them, teaching them what they know, performing innumerable functions that contribute to the running of their businesses and indeed every aspect of constructing and operating the market that has enabled them to get rich. Weill’s statement that “We didn’t rely on somebody else to build what we built” can be quickly tested. Would Weill, having built everything from scratch, be able to reproduce his fortune if stranded on a desert island?

If so, then he should be able to keep every bit of it for himself, having been solely responsible for its creation. If not, then it is reasonable to ask what portion of it was created by him, and what by others?

The Desert Island Test is a useful one to keep in mind. The primacy and ubiquity of society — so casually erased by billionaires and others justifying their fortunes — must be restored if we are to have any meaningful discussion of income and wealth, and where an individual’s claim ends and society’s begins.

One of the crucial ways that society assists individuals in generating wealth lies in the inheritance from previous generations.

This inheritance from the past is so vast it is almost beyond calculation. It encompasses every aspect of what we know as a civilization and every bit of scientific and technological advance we make use of today, going all the way back to the beginning of human language and the invention of the wheel. Measured against this vast human cultural and technological inheritance, any additional marginal advance in today’s world — even the creation of a cable television sports network — pales in significance.

The question then becomes: who is the proper beneficiary of the wealth generated by innovations based on the massive inheritance from the past — the individual innovator who adapts some tiny aspect of this past inheritance to create a slightly new product, or society as a whole (that is, all of us)?

Under our current system, the innovator captures an enormously large share of the benefits. Clearly, the innovator should be compensated for his contribution. But should he or she also be compensated for the contributions made by all the other innovators who, over the centuries, have built up a body of knowledge that made his marginal advance possible today? What share of the newly-generated wealth correctly belongs to the society that has not only nurtured him but also provided him with this rich past inheritance — without which, stranded on a desert island, he wouldn’t have the means to even keep himself warm.”

The youtube summary as well.

A double-quick quiz to see if need to read this article or not – Is the following statement true? – Egalitarian societies are in general are more economically, socially and politically sound than those where inequality more pronounced.

A double-quick quiz to see if need to read this article or not – Is the following statement true? – Egalitarian societies are in general are more economically, socially and politically sound than those where inequality more pronounced.

If you answered false go here and evaluate the evidence for yourself. If you answered true, then the following will make sense. :)

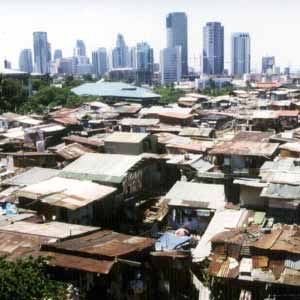

“Washington, DC – As evidence mounts that income inequality is increasing in many parts of the world, the problem has received growing attention from academics and policymakers. In the United States, for example, the income share of the top one per cent of the population has more than doubled since the late 1970s, from about eight per cent of annual GDP to more than 20 per cent recently, a level not reached since the 1920s.

While there are ethical and social reasons to worry about inequality, they do not have much to do with macroeconomic policy per se. But such a link was seen in the early part of the twentieth century: Capitalism, some argued, tends to generate chronic weakness in effective demand due to growing concentration of income, leading to a “savings glut”, because the very rich save a lot. This would spur “trade wars”, as countries tried to find more demand abroad.

From the late 1930’s onward, however, this argument faded as the market economies of the West grew rapidly in the post-World War II period and income distributions became more equal. While there was a business cycle, no perceptible tendency toward chronic demand weakness appeared. Short-term interest rates, most macroeconomists would say, could always be set low enough to generate reasonable rates of employment and demand.

Now, however, with inequality on the rise once more, arguments linking income concentration to macroeconomic problems have returned. The University of Chicago’s Raghuram Rajan, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, tells a plausible story in his recent award-winning book Fault Lines about the connection between income inequality and the financial crisis of 2008.”

This is not about “socialism” or “communism” or any of the other words the business press has corrupted. This is about what has happened and what is happening now.

“Rajan argues that huge income concentration at the top in the US led to policies aimed at encouraging unsustainable borrowing by lower – and middle-income groups, through subsidies and loan guarantees in the housing sector and loose monetary policy. There was also an explosion of credit-card debt. These groups protected the growth in consumption to which they had become accustomed by going more deeply into debt. Indirectly, the very rich, some of them outside the US, lent to the other income groups, with the financial sector intermediating in aggressive ways. This unsustainable process came to a crashing halt in 2008.

Joseph Stiglitz in his book Freefall and Robert Reich in his Aftershock have told similar stories, while economists Michael Kumhof and Romain Ranciere have devised a formal mathematical version of the possible link between income concentration and financial crisis. While the underlying models differ, the Keynesian versions emphasise that if the super-rich save a lot, ever-increasing income concentration can be expected to lead to a chronic excess of planned savings over investment.

Macroeconomic policy can try to compensate through deficit spending and very low interest rates. Or an undervalued exchange rate can help to export the lack of domestic demand. But if the share of the highest income groups keeps rising, the problem will remain chronic. And, at some point, when public debt has become too large to allow continued deficit spending, or when interest rates are close to their zero lower bound, the system runs out of solutions.”

So, consider the implications of a monetary policy that encourages people not to hold onto gratuitous wealth. The 90% tax rate on 3 million and above seems a little less unseemly if it can spurn economic growth and development.

“This story has a counterintuitive dimension. Is it not the case that the problem in the US has been too little savings, rather than too much? Doesn’t the country’s persistent current-account deficit reflect excessive consumption, rather than weak effective demand?

The recent work by Rajan, Stiglitz, Kumhof, Ranciere and others explains the apparent paradox: Those at the very top financed the demand of everyone else, which enabled both high employment levels and large current-account deficits. When the crash came in 2008, massive fiscal and monetary expansion prevented US consumption from collapsing. But did it cure the underlying problem?

Although the dynamics leading to increased income concentration have not changed, it is no longer easy to borrow and in that sense another boom-and-bust cycle is unlikely. But that raises another difficulty. When asked why they do not invest more, most firms cite insufficient demand. But how can domestic demand be strong if income continues to flow to the top?

Consumption demand for luxury goods is unlikely to solve the problem. Moreover, interest rates cannot become negative in nominal terms and rising public debt may increasingly disable fiscal policy.

So, if the dynamics fuelling income concentration cannot be reversed, the super-rich save a large fraction of their income, luxury goods cannot fuel sufficient demand, lower-income groups can no longer borrow, fiscal and monetary policies have reached their limits, and unemployment cannot be exported, an economy may become stuck.”

Is this a hate the rich tract? No, it is not. It is an article merely identifying a probable framework behind what is going on in the US economy.

“The early 2012 upturn in US economic activity still owes a lot to extraordinarily expansionary monetary policy and unsustainable fiscal deficits. If income concentration could be reduced as the budget deficit was reduced, demand could be financed by sustainable, broad-based private incomes. Public debt could be reduced without fear of recession, because private demand would be stronger. Investment would increase as demand prospects improved.

This line of reasoning is particularly relevant to the US, given the extent of income concentration and the fiscal challenges that lie ahead. But the broad trend toward larger income shares at the top is global and the difficulties that it may create for macroeconomic policy should no longer be ignored.”

This article supports the idea that a more egalitarian society is a more healthy economic society. I just wonder if the US policy makers have enough political will to enact this possible solution to some of the economic problems facing the US.

The ongoing media campaign to make the economy the monofocus of our societies continues on unabated. Do almost any news search and you will see economic principles overlaid and tied to the idea that somehow they are related to how healthy and how “good” a society actually is. Economic health is but one part of a successful society as a strength of a society not only lies in its economy but in its culture and even more importantly, its people. Jeffry Sachs opines on a better way of analyzing and structuring a society:

The ongoing media campaign to make the economy the monofocus of our societies continues on unabated. Do almost any news search and you will see economic principles overlaid and tied to the idea that somehow they are related to how healthy and how “good” a society actually is. Economic health is but one part of a successful society as a strength of a society not only lies in its economy but in its culture and even more importantly, its people. Jeffry Sachs opines on a better way of analyzing and structuring a society:

“We live in a time of high anxiety. Despite the world’s unprecedented total wealth, there is vast insecurity, unrest, and dissatisfaction. In the United States, a large majority of Americans believe that the country is “on the wrong track”. Pessimism has soared. The same is true in many other places.

Against this backdrop, the time has come to reconsider the basic sources of happiness in our economic life. The relentless pursuit of higher income is leading to unprecedented inequality and anxiety, rather than to greater happiness and life satisfaction. Economic progress is important and can greatly improve the quality of life, but only if it is pursued in line with other goals.”

Let me reassure you skeptical reader, a more egalitarian society is not only better for its people, it is better for productivity as well. What its bad for, capital accumulation and socialism for the rich.

“First, we should not denigrate the value of economic progress. When people are hungry, deprived of basic needs such as clean water, health care, and education, and without meaningful employment, they suffer. Economic development that alleviates poverty is a vital step in boosting happiness.

Second, relentless pursuit of GNP to the exclusion of other goals is also no path to happiness. In the US, GNP has risen sharply in the past 40 years, but happiness has not. Instead, single-minded pursuit of GNP has led to great inequalities of wealth and power, fueled the growth of a vast underclass, trapped millions of children in poverty, and caused serious environmental degradation.”

I would add here, the growth of the courtier corporate media whose job it is to reframe the massive inequality and unjust conditions prevalent in the US as “normal” and manage to get the poor people to actually fight against reforms that would benefit them (see the dismal failure instituting universal healthcare in the US).

“Third, happiness is achieved through a balanced approach to life by both individuals and societies. As individuals, we are unhappy if we are denied our basic material needs, but we are also unhappy if the pursuit of higher incomes replaces our focus on family, friends, community, compassion, and maintaining internal balance. As a society, it is one thing to organise economic policies to keep living standards on the rise, but quite another to subordinate all of society’s values to the pursuit of profit.

Yet politics in the US has increasingly allowed corporate profits to dominate all other aspirations: fairness, justice, trust, physical and mental health, and environmental sustainability. Corporate campaign contributions increasingly undermine the democratic process, with the blessing of the US Supreme Court”

Profits before people, who rather than rightly blame the corporate oligarchy for their misery funnel their discontent toward their government. Of course, the government corrupted by corporate interests, should be a focus of scrutiny but at the moment, the focus of the rage and anger of the American people is mostly displaced.

“Fourth, global capitalism presents many direct threats to happiness. It is destroying the natural environment through climate change and other kinds of pollution, while a relentless stream of oil-industry propaganda keeps many people ignorant of this. It is weakening social trust and mental stability, with the prevalence of clinical depression apparently on the rise. The mass media have become outlets for corporate “messaging”, much of it overtly anti-scientific, and Americans suffer from an increasing range of consumer addictions.”

Consumption is not a way to happiness, it is but a mere false paradise of shallow contrivances, moral turpitude and ethical decay.

“Fifth, to promote happiness, we must identify the many factors other than GNP that can raise or lower society’s well-being. Most countries invest to measure GNP, but spend little to identify the sources of poor health (like fast foods and excessive TV watching), declining social trust, and environmental degradation. Once we understand these factors, we can act.

The mad pursuit of corporate profits is threatening us all. To be sure, we should support economic growth and development, but only in a broader context: one that promotes environmental sustainability and the values of compassion and honesty that are required for social trust.”

What? A balance between rapacious capitalism and social, ethical and environmental concerns? Is it possible? Of course it is possible, but needs to come from outside the current political superstructure of Canada and the United States. The people of the Western countries need to organize (labour unions are a great place to start, as the represent people as opposed to business interests) and campaign for a balanced society, as opposed to the GNP fixated, world destroying paradigm we currently inhabit.

Just picking up the Spirit Level again, and finding great stuff to share.

Just picking up the Spirit Level again, and finding great stuff to share.

As a way of creating a more egalitarian society, employee ownership and control have many advantages. First, it enables a process of social emancipation as people become members of a team. Second, it puts the scale of earning differentials ultimately under democratic control:if the body of employees want big income differentials they could choose to keep them. Third it involves a very substantial redistribution of wealth from external share holders to employees and a simultaneous redistribution of the income from that wealth. In this context, that is a particularly important advantage. Fourth, it improves productivity and so has a competitive advantage. Fifth, it increases the likelihood that people will regain the experience of community. And sixth, it is likely to improve sociability in the wider society.

The real reward however, is not simply to have a few employee-owned companies in a society still dominated by hierarchical ideology and status-seeking, but to have a society of people freer those divisions.

– The Spirit Level:Why Equality is Better for Everyone. p.260-261.

Yes, gentle readers, a more a egalitarian society is better for everyone. What a concept eh? :)

It is always nice to see the patriarchy at work. Devaluing half the population is just peachy keen here in good ‘ole Alberta.

It is always nice to see the patriarchy at work. Devaluing half the population is just peachy keen here in good ‘ole Alberta.

The Parkland Institute reports:

“A new fact sheet, entitled “Women’s equality a long way off in Alberta” shows a persistent wage gap between women and men, despite the 2002-2007 oilsands boom. Alberta is also the only province/territory without any government ministry or advisory council on the status of women.

Alberta women who work full-year, full-time earn just 66% of what men earn. The Canadian average earnings gap is 72%.”

It gets even more fantastic if you read the executive summary! Our heroic Premier is a little busy licking the spittle off the lips of the oil and gas industry he really does care about the woman-folk, honest.

Your opinions…