You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘History’ tag.

The Age of Discovery was not a morality play. It was a capability leap. Between the late 1400s and the 1600s, Europeans built a durable system of oceanic navigation, mapping, and logistics that connected continents at scale. That system reshaped trade, ecology, science, and eventually politics across the world.

None of this requires sanitizing what came with it. Disease shocks, conquest, extraction, and slavery were not side notes. They were part of the story. The problem is what happens when modern retellings keep only one side of the ledger. When “discovery” is taught as a synonym for “oppression,” history stops being inquiry and becomes a single moral script.

What the era achieved

The Age of Discovery solved practical problems that had limited long-range sea travel: how to travel farther from coasts, how to fix position reliably, and how to represent the world in a form that could be used again by the next crew.

Routes mattered first. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and helped establish the sea-route logic that linked the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean world. That made long voyages less like stunts and more like repeatable corridors.

Maps made it scalable. In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller’s map labeled “America” and presented the newly charted lands as a distinct hemisphere in European cartography. In 1569, Mercator’s projection made course-setting more practical by letting navigators plot constant bearings as straight lines. These were not aesthetic achievements. They were infrastructure for a global system.

Instruments and technique followed. Mariners relied on celestial measurement, and Europeans benefited from earlier work in the Islamic world and medieval transmission routes that carried astronomical knowledge and instrument development into Europe. This is worth stating plainly because it strengthens the real point: the Age of Discovery was not magic. It was the synthesis and scaling of knowledge into a logistical machine.

Finally, there was proof of global integration. Magellan’s expedition, completed after his death by Juan Sebastián del Cano, achieved the first circumnavigation. Whatever moral judgments one makes about the broader era, this was a genuine expansion of what humans could do and know.

What it cost

The same system that connected worlds also carried catastrophe.

Indigenous depopulation after 1492 was enormous. Scholars debate the causal mix across regions, but the scale is not seriously in dispute. One influential synthesis reports a fall from just over 50 million in 1492 to just over 5 million by 1650, with Eurasian diseases playing a central role alongside violence, displacement, and social disruption.

The transatlantic slave trade likewise expanded into a vast engine of forced migration and brutal labor. Best estimates place roughly 12.5 million people embarked, with about 10.7 million surviving the Middle Passage and arriving in the Americas. These are not “complications.” They are central moral facts.

And the Columbian Exchange, often simplified into “new foods,” was a sweeping biological and cultural transfer that included crops and animals, but also pathogens and ecological disruption. It permanently altered diets, landscapes, and power.

A reader can acknowledge all of that and still resist a common conclusion: that the entire era should be treated as a civilizational stain rather than a mixed human episode with world-changing outputs.

The Exchange is the model case for a full ledger

A fact-based account has to hold two truths at once.

First, the biological transfer had large, measurable benefits. Economic historians have argued that a single crop, the potato, can plausibly explain about one-quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900. That is a civilizational consequence, not an opinion.

Second, the same transoceanic link that moved calories also moved coercion and disease. That is not a footnote. It is part of the mechanism.

The adult position is not denial and not self-flagellation. It is proportionality.

Where “critical theory” helps, and where it can deform

Critical theory is not one thing. In the broad sense, it names a family of approaches aimed at critique and transformation of society, often by making power, incentives, and hidden assumptions visible. In that role, it can correct older triumphalist histories that ignored victims and treated conquest as background noise.

The failure mode appears when the lens becomes total. When domination becomes the only explanatory variable, achievement becomes suspect simply because it is achievement, and complexity is treated as apology. The story turns into prosecution.

One can see the tension in popular history writing. Howard Zinn’s project, for example, explicitly recasts familiar episodes through the eyes of the conquered and the marginalized. That corrective impulse can be valuable. But critics such as Sam Wineburg have argued that the method often trades multi-causal history for moral certainty, producing a “single right answer” style of interpretation rather than a discipline of competing explanations. The risk is that students learn a posture instead of learning judgment.

A parallel point is worth making for Indigenous-centered accounts. Works like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s are explicit that “discovery” is often better described as invasion and settler expansion. Even when one disagrees with some emphases, the existence of that challenge is healthy. It forces the older story to grow up.

But there is a difference between correction and replacement. Corrective history adds missing facts and voices. Replacement history insists there is only one permissible meaning.

Verdict: defend the full ledger

Western civilization does not need to be imagined as flawless to be defended as consequential and often beneficial. The Age of Discovery expanded human capabilities in navigation, cartography, and global integration. It also produced immense suffering through disease collapse, coercion, and slavery.

A healthy civic memory holds both sides of that ledger. It teaches the costs without denying the achievements, and it refuses any ideology that demands a single moral story as the price of belonging.

References

Bartolomeu Dias (1488) — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bartolomeu-Dias

Recognizing and Naming America (Waldseemüller 1507) — Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/collections/discovery-and-exploration/articles-and-essays/recognizing-and-naming-america/

Mercator projection — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/science/Mercator-projection

Magellan and the first circumnavigation; del Cano — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-Magellan

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Sebastian-del-Cano

Mariner’s astrolabe and transmission via al-Andalus — Mariners’ Museum

European mariners owed much to Arab astronomers — U.S. Naval Institute (Proceedings)

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1992/december/navigators-1490s

Indian Ocean trade routes as a pre-existing global network — OER Project

https://www.oerproject.com/OER-Materials/OER-Media/HTML-Articles/Origins/Unit5/Indian-Ocean-Routes

Indigenous demographic collapse (1492–1650) — British Academy (Newson)

Transatlantic slave trade estimates — SlaveVoyages overview; NEH database project

https://legacy.slavevoyages.org/blog/brief-overview-trans-atlantic-slave-trade

https://www.neh.gov/project/transatlantic-slave-trade-database

Potato and Old World population/urbanization growth — Nunn & Qian (QJE paper/PDF)

Click to access NunnQian2011.pdf

Critical theory (as a family of theories; Frankfurt School in the narrow sense) — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/

Zinn critique: “Undue Certainty” — Sam Wineburg, American Educator (PDF)

https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2012-2013

Indigenous-centered framing (as a counter-story) — Beacon Press (Dunbar-Ortiz)

https://www.beacon.org/An-Indigenous-Peoples-History-of-the-United-States-P1164.aspx

The last veterans of the Great War departed this world decades ago; those who endured the trenches and bombardments of the Second World War now number fewer than a thousand, most in their late nineties or beyond. With them vanishes the final tether of direct witness to the twentieth century’s cataclysms. What fades is not merely a generation but a form of moral authority — the living memory that once stood before us in uniform and silence. We have reached a civilizational inflection point: the moment when history ceases to be personal recollection and becomes curated narrative, vulnerable to distortion, neglect, or deliberate revision.

This transition demands vigilance. Memory, once embodied in a stooped figure wearing faded medals, could command reverence simply by existing. Now it resides in archives, textbooks, and the contested arena of public commemoration. The risk is not that the past will vanish entirely — curiosity and conscience ensure fragments endure. The greater peril is that it will be instrumentalised: stripped of complexity and pressed into service for transient ideological projects. A battle becomes a hashtag, a sacrifice a soundbite, a hard-won lesson a slogan detached from the blood that purchased it.

Edmund Burke reminded us that society is a partnership not only among the living, but between the living, the dead, and those yet unborn. This compact imposes obligations. We inherit institutions, norms, and liberties refined through centuries of trial, error, and atonement. To treat them as disposable because their origins lie beyond living memory is to saw off the branch on which we sit. The trenches of the Somme, the beaches of Normandy, the frozen forests of the Ardennes—these were not abstractions of geopolitics but crucibles in which the consequences of appeasement, militarised grievance, and contempt for constitutional restraint were written in blood.

The lesson is not that war is always avoidable; history disproves such sentimentalism. It is that certain patterns recur with lethal predictability when prudence is discarded. The erosion of intermediary institutions, the inflation of executive power, the substitution of mass emotion for deliberation—these were the preconditions that turned stable nations into abattoirs. To recognise them requires neither nostalgia nor ancestor worship, only the intellectual honesty to trace cause and effect across generations.

Conserving society in the Burkean sense is therefore active, not passive. It means cultivating the habits that sustain ordered liberty: deference to proven custom tempered by principled reform; respect for the diffused experience of the many rather than the concentrated will of the few; and humility before the limits of any single generation’s wisdom. Remembrance Day, properly observed, is not a requiem for the dead but a summons to the living. It reminds us that the peace we enjoy is borrowed, not owned — and that the interest payments come due in vigilance, discernment, and the quiet courage to defend what has been painfully built.

As the century that began in Sarajevo and ended in Sarajevo’s shadow recedes from living memory, the obligation deepens. We must read the dispatches, study the treaties, weigh the speeches, and above all resist the temptation to flatten the past into morality plays that flatter the present. Only thus do we honour the fallen: not with poppies alone, but with societies sturdy enough to vindicate their sacrifice.

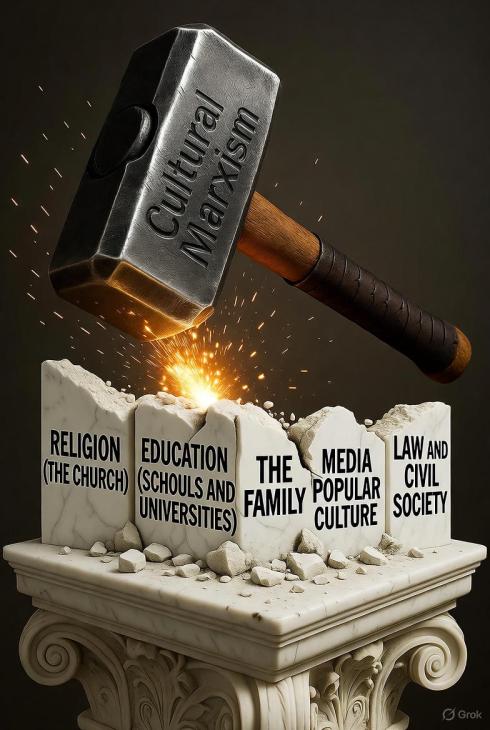

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist imprisoned by Mussolini, changed political strategy forever by shifting revolution from the factory floor to the realm of culture. His concept of cultural hegemony—the quiet capture of schools, media, and moral institutions—remains the blueprint for the modern Left’s “long march through the institutions.” Understanding him is key to understanding how ideology became the new battlefield of Western democracy.

Why the twentieth century’s most subversive Marxist remains essential to understanding our political moment.

Antonio Gramsci has become a ghostly presence in today’s politics—invoked by both left and right, praised as a prophet of cultural liberation and blamed as the architect of “Cultural Marxism.” Yet few who use his name understand the subtlety of what he actually proposed. Gramsci, an Italian communist jailed by Mussolini from 1926 until his death in 1937, recognized that Western societies could not be overthrown by economic revolution alone. The real battleground, he argued, lay in the culture—in the stories a society tells itself about who it is, what it values, and what it considers “common sense.”

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci dissected how ruling elites maintain power not only through economic control or state coercion but through the manufacture of consent—what he called cultural hegemony. When the public unconsciously accepts elite norms as their own, open coercion becomes unnecessary. The power structure endures because people cannot easily imagine alternatives.

From Marx to Culture: The Pivot that Changed the Left

This insight quietly revolutionized the Marxist project. Where Marx saw power rooted primarily in economics, Gramsci saw it reproduced through education, religion, art, the press, and civic institutions—what he called “civil society.” If these were the true engines of social continuity, then a revolutionary movement must capture them before capturing the state. The task, therefore, was not simply to seize the means of production but to seize the means of persuasion.

That shift—from factory to faculty, from economics to ideology—birthed what would later be called Cultural Marxism. It gave rise to the post-war New Left and, through the Frankfurt School, to a range of “critical” theories that continue to shape university life and activist politics. Power was no longer viewed as residing primarily in class relations but in language, identity, and culture. Gramsci’s “war of position”—a slow, patient infiltration of cultural institutions—became the model.

The Five Fronts of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci never offered a neat checklist, but his writings identify five interlocking domains where the battle for hegemony is fought—and where Western institutions have since seen the most visible transformations:

- Religion and Moral Order – For centuries, the Church anchored Western moral consensus. Gramsci saw it as the spiritual foundation of bourgeois power. Undermining or secularizing that foundation was essential to remaking moral consciousness.

- Education and the Intelligentsia – Schools and universities, he observed, do not merely transmit knowledge; they reproduce ideology. Control the curriculum, train the teachers, shape the young—and you shape tomorrow’s society.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, cinema, art, and now digital media cultivate public sentiment. Altering how people speak, joke, and imagine themselves can shift the moral vocabulary of an entire civilization.

- Civil Society and Voluntary Institutions – Clubs, unions, NGOs, and advocacy groups form the connective tissue between individuals and the state. They generate the “organic intellectuals” who articulate a new worldview and lend legitimacy to political change.

- Law, Politics, and the Administrative State – Finally, cultural transformation must be consolidated through legal norms, policy, and bureaucratic language, ensuring that the new values become institutional reflexes rather than contested ideas.

Each domain is a theatre in the long “war of position.” The aim is not an immediate coup but the gradual erosion of inherited norms until the revolutionary outlook feels like common sense.

Why Gramsci Still Matters

Gramsci’s legacy is paradoxical. His analysis was intellectually brilliant—but by detaching revolution from economics and anchoring it in culture, he supplied future radicals with a strategy for subverting liberal democracy from within. The New Left of the 1960s and its academic descendants adopted his playbook, translating class struggle into struggles over race, gender, language, and identity. In this sense, Gramsci stands as both the diagnostician and the progenitor of our current ideological turbulence.

For those tracing the lineage of today’s cultural battles, reading Gramsci is essential. His theory of hegemony explains why institutions that once served as stabilizing forces—universities, churches, professional guilds, and even the arts—have become arenas of moral and political conflict. It also clarifies why dissenters within those institutions are treated not as intellectual adversaries but as heretics.

Reading the Intellectual Landscape

This essay continues the Learning the Lay of the Land series here at Dead Wild Roses, which maps the ideas that reshaped Western political thought:

- Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism — how ideological certainty breeds totalitarian temptation.

- Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and the Birth of Cultural Hegemony — a deep dive into his original ideas.

- Orwell’s Politics and the English Language — how linguistic corruption becomes political control.

- Mill’s On Liberty — a defence of intellectual freedom against the new orthodoxy.

Together they outline the terrain of our ideological crisis: from Arendt’s warning about totalitarian habits of mind, through Gramsci’s theory of cultural capture, to Orwell’s exposure of linguistic manipulation and Mill’s insistence on free thought.

Closing Reflection

Gramsci’s insight—that the health of a society depends on who defines its common sense—remains the axis on which our modern conflicts turn. Understanding his ideas is not an act of homage, but of inoculation. To preserve a free and open civilization, one must know precisely how it can be subverted—and Gramsci told us, in meticulous detail, how that can be done.

Primary Sources

Gramsci, Antonio. *Selections from the Prison Notebooks*. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971. (Core text for concepts of cultural hegemony, war of position, civil society, and organic intellectuals; selections from Notebooks 1–29, written 1929–1935.)

Secondary Sources

Arendt, Hannah. *The Origins of Totalitarianism*. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. (Referenced in series context for ideological escalation into totalitarianism.)

Mill, John Stuart. *On Liberty*. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859. (Referenced in series context as counterpoint to hegemonic orthodoxy.)

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” *Horizon* 13, no. 76 (April 1946): 252–265. (Referenced in series context for linguistic mechanisms of ideological control.)

Additional Contextual Works

Jay, Martin. *The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950*. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973. (Provides linkage between Gramsci’s cultural pivot and post-war Critical Theory.)

Rudd, Mark. “The Long March Through the Institutions: A Memoir of the New Left.” In *The Sixties Without Apology*, edited by Sohnya Sayres et al., 201–218. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. (Illustrates practical adoption of Gramscian strategy in 1960s activism.)

Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil remains one of the twentieth century’s most incisive dissections of moral failure. Published in 1963, the book emerged from Arendt’s firsthand reporting on the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, a mid-level Nazi bureaucrat whose role in orchestrating the deportation of millions of Jews to death camps defined the Holocaust’s logistical horror. Expectations ran high for a portrait of unalloyed monstrosity, yet Arendt delivered something far more unsettling: a portrait of profound ordinariness. Eichmann was no ideological zealot or sadistic fiend, but a careerist adrift in clichés and administrative jargon, driven by ambition and an unswerving commitment to hierarchy. From this unremarkable figure, Arendt forged her enduring concept of the banality of evil, a framework that exposes how systemic atrocities arise not from demonic intent but from the quiet abdication of critical thought.

The Trial That Shattered Expectations

Arendt arrived in Jerusalem as a correspondent for The New Yorker, tasked with chronicling the prosecution of Eichmann, the architect of the Nazis’ “Final Solution” in practice if not in origin. What she witnessed defied the trial’s dramatic staging. Eichmann, perched in his glass booth, projected not menace but mediocrity. He droned on in a flat, bureaucratic patois, insisting his actions stemmed from dutiful obedience rather than personal malice. “I never killed a Jew,” he protested, as if the euphemism absolved the machinery he oiled. This was no Iago or Macbeth, but a joiner par excellence: shallow, conformist, and utterly unable to grasp the human weight of his deeds. Arendt’s revulsion crystallized mid-trial, in her notebooks, where she first sketched the phrase that would redefine her legacy. The banality of evil was born not from Eichmann’s depravity, but from his incapacity for reflection—a thoughtlessness that rendered him complicit in genocide without the depth to comprehend it.

Unpacking the Banality: From Demonic to Mundane

At its core, the banality of evil upends the romanticized view of wickedness as inherently profound or radical. Evil, Arendt contended, often manifests as banal: the work of unimaginative souls who drift through conformity, failing to interrogate their roles in larger systems. Eichmann exemplified this through his linguistic sleight of hand. He evaded the raw truth of extermination, speaking instead of “transportations” and “processing,” terms that sanitized slaughter into spreadsheet entries. Hatred played little part; obedience, careerism, and social inertia sufficed. The terror lay in his normalcy. As Arendt observed, evil flourishes not among isolated monsters but in societies where individuals relinquish moral judgment to rules, authorities, or routines. This banality, she later clarified, arises from an active refusal to exercise judgment, transforming ordinary people into cogs of catastrophe.

Arendt wove this insight into her broader philosophical tapestry, where thinking emerges as the essential moral safeguard. In the Socratic tradition, genuine thought demands we question the rightness of our actions, bridging the gap between knowledge and ethics. Eichmann’s failure was not intellectual deficiency alone, but a willful suspension of this faculty—substituting slogans and protocols for scrutiny. She identified thoughtlessness as totalitarianism’s hallmark, a regime that trains citizens to obey without asking why, eroding the pluralistic dialogue vital to human freedom. Against this, Arendt posited “natality,” the human capacity for birth and renewal, as a counterforce: each new beginning compels us to initiate thought, disrupting entrenched banalities.

The Firestorm of Controversy

Arendt’s conclusions ignited immediate backlash. Critics, including Jewish intellectuals like Gershom Scholem, accused her of exonerating Eichmann and scapegoating victims by critiquing the Jewish councils’ coerced cooperation with Nazi demands. Her dispassionate tone struck many as callous, diluting the Holocaust’s singularity into a lesson in human frailty. Yet Arendt sought neither absolution nor minimization; her aim was diagnostic. Evil in bureaucratic modernity, she argued, stems from collective complicity, not just from fanatics. The ordinary enablers—those who obey without question—sustain the system as surely as the architects. This polemic endures, with debates persisting over whether Arendt undervalued antisemitism’s visceral role, but her thesis has proven resilient, outlasting the initial fury.

Philosophical Stakes: Redefining Moral Agency

Arendt’s innovation lies in relocating moral responsibility from sentiment to cognition. Agency begins not with feeling but with thought: the deliberate act of judging actions against universal principles. This aligns her work with deeper epistemic concerns, where unexamined beliefs pave the way for ethical collapse. Without the courage to probe “Is this true? Is this right?”, reasoning devolves into rote compliance. The banality of evil thus warns of disengagement in any apparatus—state, corporation, or ideology—where “just following orders” masks profound harm. In an age of institutional sprawl, her call to vigilant judgment remains a bulwark against the mindless perpetuation of injustice.

Lessons for Our Fractured Age: Thoughtlessness in Ideological Currents

Arendt’s framework offers stark lessons amid the ascendance of critical social constructivism, woke Marxism, and gender ideology—movements that, in their zealous conformity, risk replicating the very thoughtlessness she decried. Critical social constructivism, with its insistence that reality bends to narrative power, echoes Eichmann’s euphemistic detachment: truths are “constructed” not discovered, fostering a relativism where evidence yields to doctrinal fiat. Proponents, often ensconced in academic silos, propagate this without interrogating its epistemic costs, much as Arendt saw totalitarianism erode pluralistic inquiry. The result? A moral landscape where dissent is pathologized as “harm,” inverting Socratic dialogue into inquisitorial purity tests.

Woke Marxism, blending identity politics with class warfare rhetoric, amplifies this banality through performative allegiance. What begins as equity advocacy devolves into bureaucratic rituals—DEI mandates, cancel campaigns—that demand uncritical adherence, sidelining the reflective judgment Arendt deemed essential. Critics from leftist traditions note how this mirrors the “administrative massacres” she analyzed, where ideological slogans supplant ethical scrutiny, enabling everyday cruelties under the guise of progress. Ordinary adherents, like Eichmann’s clerks, comply not from malice but from careerist inertia, blind to the dehumanization they abet.

Gender ideology presents perhaps the most poignant parallel, transforming biological verities into fluid “affirmations” via sanitized language that obscures irreversible interventions. Global market projections for sex reassignment surgeries, valued at $3.13 billion in 2025, anticipate reaching $5.21 billion by 2030, underscoring this commodified banality: procedures framed as “care” evade the long-term harms to minors, much as Nazi logistics masked extermination. Voices like J.K. Rowling invoke Arendt directly, highlighting how euphemisms prevent equating these acts with “normal” knowledge of human development. Shallow conformity here—fueled by fear of ostracism—propagates misogynistic erosions of women’s spaces and youth safeguards, all without the depth to confront consequences.

Arendt’s antidote is uncompromising: reclaim thinking as moral praxis. In our screen-lit caves, where algorithms curate consensus and ideologies brook no doubt, we must cultivate epistemic humility—the willingness to question, to pluralize, to judge anew. Only thus can we arrest banality’s creep, ensuring that goodness, radical in its depth, prevails over evil’s empty routine. Thoughtlessness is not fate; it is choice. And in choosing reflection, we honor the dead by fortifying the living against their shadows.

References

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (For concepts of natality and action.)

Berkowitz, R. (2013). “The Banality of Hannah Arendt.” The New York Review of Books, June 6. (On ongoing debates of her thesis.)

Mordor Intelligence. (2024). Sex Reassignment Surgery Market Size, Trends, Outlook 2025–2030. Retrieved October 5, 2025, from https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/sex-reassignment-surgery-market.

Rowling, J. K. [@jk_rowling]. (2024, December 28). “This astounding paper reminds me of Hannah Arendt’s The Banality of Evil…” [Post]. X. https://x.com/jk_rowling/status/1873048335193653387.

Scholem, G. (1964). “Reflections on Eichmann: The Trial of the Historian.” Encounter, 23(3), 25–31. (Open letter critiquing Arendt’s portrayal.)

Villa, D. (1996). Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (For connections to Socratic thinking and totalitarianism.)

The British Empire, for all its flaws, wielded its vast influence as a decisive instrument in dismantling the global scourge of slavery—a system that violated human dignity on a global scale. By the late 18th century, Britain’s economic and naval dominance positioned it uniquely to challenge the transatlantic slave trade, which it had once profited from immensely. The 1807 Slave Trade Act, driven by relentless abolitionist campaigns from figures like William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, outlawed the trade across the empire, striking a blow at the economic arteries of slavery.1 This was no mere moral posturing: Britain’s West Africa Squadron, deployed from 1808, patrolled the Atlantic, intercepting slave ships and liberating over 150,000 enslaved Africans by 1860.2 Yet the squadron’s operations were not without contradiction—many of the “liberated” were later conscripted into naval service or settled in British colonies under paternalistic regimes.

Behind these legislative shifts stood a groundswell of popular activism—thousands of petitions, boycotts of slave-grown sugar, and the mobilization of dissenting religious groups, particularly the Quakers. As J.R. Oldfield has shown, Britain’s anti-slavery effort marked one of the earliest examples of coordinated mass politics in a liberal democracy.3 This popular moral awakening fueled legislative change but faced resistance from powerful interests, particularly in the colonies. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which emancipated nearly 800,000 enslaved people across British territories, was a monumental step, but it came with caveats—planters were compensated handsomely, while freed individuals received no reparations and faced exploitative “apprenticeship” systems.4 Abolition, in this context, was less a moral epiphany than a negotiated dismantling of a profitable institution.

Britain’s abolitionist zeal extended outward, forcing other nations—such as France, Spain, and Brazil—to curtail their own slave trades through a combination of treaties, naval pressure, and economic leverage. The 1841 Quintuple Treaty bound several major European powers to suppress the transatlantic trade, demonstrating Britain’s capacity to turn moral authority into diplomatic influence.5 This was less about universal brotherhood than about asserting moral and geopolitical superiority over rivals. At home and abroad, Britain leveraged its economic clout—offering trade incentives or threatening sanctions—to coerce reluctant powers into compliance.

However, abolition did not signal the end of coerced labor; rather, it marked a transition to new forms of economic exploitation. Indentured labor, particularly from India and China, was recruited under harsh conditions and deployed across the empire to fuel plantation economies. Critics have rightly argued that this was “a new system of slavery” in all but name, replicating colonial hierarchies under the guise of freedom.6

The British Empire’s crusade against slavery, while imperfect, reshaped the global moral landscape, proving that imperial might could be harnessed for transformative ends. Its abolitionist policies rippled across the Americas, Africa, and beyond, hastening the decline of legalized slavery worldwide. By the mid-19th century, the empire’s relentless naval patrols and diplomatic arm-twisting had rendered the transatlantic trade increasingly untenable. Yet this legacy is no hagiography: Britain’s earlier profiteering from slavery and its post-abolition labor practices expose a hypocrisy that tempers its triumphs. Nonetheless, the empire’s unparalleled capacity to enforce change—through law, force, and influence—demonstrates a singular truth: no other power of the era could have so decisively tilted the scales against a centuries-old institution. The British Empire, for better or worse, was the fulcrum on which the global fight against slavery pivoted.

Footnotes

- Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery. Cambridge University Press, 2009. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abolition/9780521606592 ↩

- “The West Africa Squadron.” The National Archives, UK. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/atlantic-world/west-africa-squadron/ ↩

- Oldfield, J.R. Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilisation of Public Opinion against the Slave Trade, 1787–1807. Manchester University Press, 1995. https://manchester.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7228/manchester/9780719038570.001.0001/upso-9780719038570 ↩

- “Slavery Abolition Act 1833.” UK Parliament. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/tradeindustry/slavetrade/ ↩

- Huzzey, Richard. Freedom Burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain. Cornell University Press, 2012. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801451089/freedom-burning/ ↩

- Tinker, Hugh. A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas 1830–1920. Oxford University Press, 1974. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/a-new-system-of-slavery-9780195600749 ↩

Canada Day, celebrated every July 1st, commemorates the unification of three British colonies into the Dominion of Canada in 1867. However, the story of Canada spans thousands of years, weaving together Indigenous heritage, colonial struggles, and modern achievements. Reflecting on this history during Canada Day deepens our appreciation for the nation’s journey and the diverse peoples who have shaped it.

Indigenous Roots and European Arrival

For millennia, Indigenous peoples thrived across the land now called Canada, building sophisticated societies with unique languages, governance systems, and traditions. Nations like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy and the Anishinaabe developed complex trade networks and political alliances long before European contact. The arrival of European explorers—John Cabot in 1497 and Jacques Cartier in 1534—marked the start of a transformative era. By the 17th century, French and British settlers established colonies, with the fur trade becoming a key driver of early economic and cultural exchanges between Indigenous peoples and Europeans. The 1763 Treaty of Paris, which transferred French territories to Britain after the Seven Years’ War, and the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which recognized Indigenous land rights, laid the groundwork for future relations. The establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 further intensified European presence, often leading to tensions over land and resources with Indigenous groups like the Cree and Métis. Additionally, diseases brought by Europeans, such as smallpox, devastated Indigenous populations, reshaping demographics and power dynamics in ways still felt today. This colonial history is vital to recall on Canada Day, as it underscores the enduring presence of Indigenous communities and the complex legacy of colonization that shapes ongoing reconciliation efforts.

Confederation: The Birth of a Nation

The mid-19th century brought a push for unity among Britain’s North American colonies, driven by economic challenges and the threat of American expansion. The Charlottetown Conference of 1864 and the Quebec Conference, attended by the Fathers of Confederation like George-Étienne Cartier and Thomas D’Arcy McGee, set the stage for the British North America Act, enacted on July 1, 1867. This act created Canada by uniting Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, with Sir John A. Macdonald as its first prime minister. However, not all colonies joined immediately; Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland initially resisted, reflecting regional hesitations. Economic factors, such as the need for a unified railway system to boost trade, played a significant role in convincing colonies to join, with the Intercolonial Railway completed in 1876. The Red River Rebellion of 1869–70, led by Louis Riel, also highlighted early challenges to Confederation, as Métis and Indigenous peoples sought to protect their rights against encroaching federal authority. Confederation is the heart of Canada Day, symbolizing the beginning of self-governance and the foundation of a national identity rooted in cooperation and resilience.

The 20th Century: Defining Moments

Canada’s role in the 20th century solidified its global presence. The victory at Vimy Ridge in 1917 during World War I, where Canadian troops fought together for the first time, became a symbol of national unity and military prowess. Contributions to World War II, like the D-Day landings in 1944, further showcased Canadian courage. At home, the Great Depression of the 1930s tested the nation’s resilience, while social movements like women’s suffrage, which saw Manitoba grant women the right to vote in 1916, reshaped society. The Quiet Revolution in Quebec during the 1960s modernized the province and redefined its cultural landscape. Canada’s pioneering role in peacekeeping, starting with Lester B. Pearson’s efforts during the 1956 Suez Crisis (for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize), established the nation as a mediator on the world stage. The 1970 October Crisis, sparked by the FLQ’s separatist actions in Quebec, tested national unity and led to the controversial use of the War Measures Act. In 1982, the patriation of the Constitution and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms affirmed Canada’s independence and commitment to individual rights. These milestones, remembered on Canada Day, highlight the nation’s growth and dedication to justice and autonomy.

Modern Canada: A Mosaic of Diversity

Today, Canada embraces multiculturalism, bolstered by the Official Languages Act of 1969 and the Multiculturalism Act of 1988. Immigration trends, like the influx of refugees from Vietnam in the 1970s and Syria in the 2010s, have enriched the nation’s cultural fabric. Canada’s global role as a peacekeeper—beginning with the Suez Crisis in 1956—and its advocacy for human rights are notable, though challenges like Indigenous rights and climate change persist. The country’s response to global issues, such as signing the Paris Agreement in 2016, reflects its commitment to sustainability. Canada’s entry into free trade agreements, like NAFTA in 1994 (now USMCA), has shaped its economy, while cultural exports like the music of Céline Dion and the films of Denis Villeneuve showcase its soft power. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, launched in 2008, has also brought renewed focus to addressing historical injustices against Indigenous peoples, with its 94 Calls to Action guiding modern policy. On Canada Day, this modern history reminds us of our collective responsibility to foster inclusivity and learn from the past to build a better future.

Why It Matters on Canada Day

Canada’s history—from Indigenous resilience to colonial foundations, Confederation, and beyond—reveals a nation shaped by struggle and unity. Celebrating Canada Day is more than a tribute to 1867; it’s a moment to honor all who have contributed to Canada’s story and to reflect on the values of diversity, peace, and progress that define it today.

Bibliography for Further Reading

- Canadian Encyclopedia – A comprehensive resource on Canadian history.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en - CBC Archives – Historical articles and videos on Canada’s past.

https://www.cbc.ca/archives - Historica Canada – Interactive timelines and educational resources.

https://www.historicacanada.ca/ - Library and Archives Canada – Primary sources, including documents and photographs.

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Pages/home.aspx - University of Toronto – Department of History – Academic articles on Canadian history.

https://www.history.utoronto.ca/ - Government of Canada – Indigenous History – Information on Indigenous peoples and reconciliation.

https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100010002/1534874447533 - The Canadian Museum of History – Exhibits and resources on Canada’s past.

https://www.historymuseum.ca/ - Veterans Affairs Canada – Information on Canada’s military history.

https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history - Statistics Canada – Immigration and Diversity – Data on Canada’s demographic changes.

https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects/immigration_and_diversity - Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canada’s environmental policies and history.

https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change.html - Canada’s History Society – Articles and stories about key historical events.

https://www.canadashistory.ca/ - Parks Canada – National Historic Sites – Information on key locations in Canada’s history.

https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs

Your opinions…