You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Morality’ tag.

I am an atheist. I do not believe in God, miracles, or an afterlife. Yet I am convinced that without Christianity, the West as we know it would be in deep trouble. This is not a plea for conversion; it is a historical and institutional argument about causation, moral capital, and societal resilience. Christianity supplied the ethical vocabulary, the metaphysical glue, and the organizational scaffolding that transformed a patchwork of tribes into a civilization capable of self-correction and sustained progress. Remove it, and the structure does not stand neutral—it tends toward fragmentation and moral erosion.

Conceding the Objections

The historical record contains horrors: the Inquisition, the Crusades, witch-burnings, and biblical endorsements of slavery and stoning. The Spanish Inquisition executed 3,000–5,000 people over three and a half centuries (Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition, 1997). The Crusades may have claimed 1–3 million lives across two centuries (Thomas Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades, 2005). Leviticus prescribes death for adultery and homosexuality. These human costs cannot be denied.

Yet scale and context matter. The secular French Reign of Terror executed over 16,000 in a single year (1793–94). Twentieth-century atheist regimes accounted for roughly 100 million deaths in six decades (The Black Book of Communism, 1997). The same biblical canon that justified cruelty also contained the seeds of reform. Jesus’ “let him without sin cast the first stone” (John 8:7) and Paul’s “the letter kills, but the spirit gives life” (2 Corinthians 3:6) inspired Christian abolitionists to resist literalist cruelty. Christianity, unlike pagan or purely rational codes, possesses an internal dialectic capable of moral self-correction.

The Pre-Christian Baseline

The world Christianity inherited was ethically limited. Rome was an administrative marvel but morally parochial: one in four newborns was exposed on hillsides (W. V. Harris, 1982), gladiatorial combat entertained hundreds of thousands, and slavery was normalized by Aristotle and unchallenged by Cicero. Pagan philanthropy existed—evergetism—but it was episodic, tied to civic prestige, not universal duty.

Christianity introduced a transformative idea: every human being, slave or emperor, bore the image of God (imago Dei). Gregory of Nyssa condemned slavery as theft from the Creator in 379 CE. Constantine’s successors banned infanticide by 361 CE (Codex Theodosianus 3.3.1). These were not Enlightenment innovations; they were theological imperatives that eventually rewrote law and custom.

Institutions That Outlived Their Creed

The West’s institutional DNA is stamped with Christian influence:

- Literacy and knowledge: Monastic scriptoria preserved Virgil alongside the Vulgate. Cathedral schools evolved into Bologna (1088) and Paris (1150)—the first universities, chartered to pursue truth as a reflection of divine order.

- Care systems: Basil of Caesarea built the basilias in the fourth century, a network of hospitals, orphanages, and poor relief. No pre-Christian society systematized charity on this scale.

- Rule of law: The Decalogue’s absolute prohibitions and the Sermon on the Mount’s inward ethic created trust horizons essential for complex societies. English common law, the Magna Carta (1215), and the U.S. Declaration’s “endowed by their Creator” trace their lineage to Christian natural-law theory.

Secular analogues arrived centuries later and proved fragile without transcendent accountability. The Soviet Union inherited Orthodox hospitals but could not sustain them after purging “idealism.”

The Borrowing Fallacy

Many modern atheists condemn Leviticus yet insist on universal dignity. That norm is not self-evident; it is a Christian export. Nietzsche saw this clearly: the “death of God” would undo slave morality and return society to master morality (Genealogy of Morals, 1887). When we demand compassion from power, we are smuggling Christian principles into a secular argument. Strip away the premise, and human relations default to “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (Thucydides).

Contemporary Evidence

Secularization correlates with institutional and social atrophy. Europe’s fertility rate hovers at 1.5, and marriage and volunteerism track church attendance downward. The World Values Survey shows that religious societies retain higher interpersonal trust. The West exports human rights grounded in Christian-derived universality; competitors offer efficiency without reciprocity.

Some argue secular humanism could replace Christianity. Yet historical experience shows moral innovation without transcendent accountability is fragile: Enlightenment ethics, while intellectually powerful, required centuries of reinforcement from religiously-informed social norms to take root widely.

A Charitable Conclusion

Christians must acknowledge their tradition’s abuses alongside its capacity for self-correction. Atheists should recognize that our moral vocabulary—equality, compassion, rights—was not discovered by reason alone but forged in a crucible we no longer actively tend. The West lives off borrowed moral capital. When the account empties, we will not revert to a benign pagan golden age; we will confront efficient barbarism dressed in bureaucratic language.

Christianity is not true, in my view. But it was necessary. And it may still be.

References

- Harris, W. V. (1982). Ancient Literacy. Harvard University Press.

- Kamen, Henry. (1997). The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. Yale University Press.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2005). The New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Popper, Karl. (1972). The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton University Press.

- The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (1997). Stéphane Courtois et al. Harvard University Press.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1887). On the Genealogy of Morals.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. Rex Warner. Penguin Classics, 1972.

- Codex Theodosianus. (438 CE). Codex of the Theodosian Code, Book 3, Title 3, Law 1.

- World Values Survey. (2017). “Wave 7 (2017–2020) Survey Data.” Retrieved from https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org.

In this series, we’ve explored the oppressor/oppressed lens—a framework that divides society into those with power (oppressors) and those without (oppressed). The first post traced its roots to the Combahee River Collective, Paulo Freire, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, showing how intersectionality and class consciousness shaped a tool for naming systemic injustice, though Freire’s ideological focus sidelined factual learning. The second post examined its modern applications through Judith Butler’s fluid view of power, Robin DiAngelo’s struggle session-like workshops, and John McWhorter’s critique of its dogmatic turn. While the lens has illuminated real harms, it often oversimplifies morality, fosters division, and stifles dialogue. In this final post, we’ll dig into its deepest limitations with insights from Peter Boghossian, James Lindsay, Jonathan Haidt, bell hooks, and Joe L. Kincheloe. Then, we’ll propose a more nuanced moral framework for navigating our complex world.

The Lens’s Fatal Flaws

The oppressor/oppressed lens promises clarity: identify the oppressor, uplift the oppressed, and justice follows. But in practice, it falters as a universal moral guide. It reduces people to group identities, suppresses critical inquiry, and fuels tribalism, leaving little room for the messy realities of human experience. Five thinkers help us see why—and point toward a better way.

Peter Boghossian: Stifling Inquiry

Peter Boghossian, in How to Have Impossible Conversations (2019), argues that the oppressor/oppressed lens creates ideological echo chambers where questioning is taboo. He describes how labeling someone an “oppressor” based on identity—like race or gender—shuts down dialogue, as dissent is framed as defending privilege. For example, in a college seminar, a student questioning a claim about systemic racism might be silenced with accusations of “fragility,” echoing DiAngelo’s tactics. Boghossian emphasizes that true critical thinking requires open inquiry, not moral litmus tests. The lens’s binary framing discourages this, turning discussions into battles over who’s “right” rather than what’s true. By prioritizing ideology over evidence, it undermines the very understanding it seeks to foster.

James Lindsay: Ideological Rigidity

James Lindsay, through his work in Cynical Theories (2020) and on New Discourses (https://newdiscourses.com/), argues that the oppressor/oppressed lens, rooted in critical theory, imposes a power-obsessed worldview that distorts reality and suppresses dialogue. He contends that the lens reduces every issue—from education to science—to a battle between oppressors and oppressed, deeming “oppressed” perspectives inherently valid and “oppressor” ones suspect. For example, Lindsay cites school restorative justice programs, which often prioritize systemic oppression narratives over individual accountability, leading to increased classroom disruption (New Discourses Podcast, Ep. 160). On X, a scientific study might be dismissed as “colonial” if it challenges the lens, ignoring empirical evidence. Lindsay warns that this creates a moral absolutism where questioning the lens is equated with upholding oppression, stifling reason and fostering division. Like Freire’s class consciousness, this rigid ideology prioritizes narrative over nuance, limiting our ability to address complex problems.

Jonathan Haidt: Moral Tribalism

Jonathan Haidt, in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and The Righteous Mind (2012), shows how the lens fuels moral tribalism—dividing society into “us” (the oppressed or their allies) and “them” (the oppressors). He argues that it amplifies cognitive distortions, like catastrophizing, where minor slights are seen as existential threats. For example, a workplace disagreements might escalate into accusations of “oppression” if framed through the lens, as seen in DiAngelo-inspired DEI sessions. Haidt’s research on moral foundations suggests humans value not just fairness (the lens’s focus) but also loyalty, care, and liberty. By fixating on oppression, the lens neglects these other values, alienating people who might otherwise support justice. This tribalism turns potential allies into enemies, undermining collective progress.

bell hooks: Division Over Solidarity

bell hooks, in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), critiques the oppressor/oppressed lens for fostering division rather than solidarity. She argues that pitting groups against each other—men vs. women, white vs. Black—reinforces hierarchies rather than dismantling them. For hooks, true liberation requires love and mutual understanding, not just naming oppressors. For instance, a feminist movement that vilifies all men as oppressors, as the lens might encourage, alienates male allies and ignores how class or race complicates gender dynamics. hooks’ vision of a “beloved community” emphasizes shared humanity over binary conflict, offering a moral framework that transcends the lens’s zero-sum approach.

Joe L. Kincheloe: Contextual Complexity

Joe L. Kincheloe, in Critical Constructivism: A Primer (2005), offers a nuanced alternative to the oppressor/oppressed lens by emphasizing that knowledge and power are co-constructed through social, cultural, and historical contexts. Building on social constructivism, Kincheloe argues that truth is negotiated through critical dialogue and evidence, not merely a function of power, rejecting the radical relativism that can accompany postmodern interpretations. He advocates empowering students to analyze their realities collaboratively, questioning how power shapes knowledge without reducing issues to a binary of oppressors vs. oppressed. For example, a teacher might guide students to investigate how local economic policies impact their community, fostering shared inquiry that considers multiple perspectives and real-world consequences. Kincheloe critiques universalizing frameworks like the oppressor/oppressed lens for ignoring local nuances and individual agency. By promoting a critical consciousness rooted in contextual, evidence-based analysis, he supports a moral framework that values complexity and collaboration over ideological absolutes.

A Better Way Forward

The oppressor/oppressed lens has illuminated systemic wrongs, from Maya’s workplace barriers to the interlocking oppressions Crenshaw described. But as Boghossian, Lindsay, Haidt, hooks, and Kincheloe show, it falls short as a moral compass. It stifles inquiry, rigidifies thought, fuels tribalism, divides communities, and oversimplifies power. So, what’s the alternative?

A more nuanced moral framework starts with three principles:

- Context Over Categories: Instead of judging people by group identities, consider their actions and circumstances. A white worker struggling with poverty isn’t inherently an “oppressor,” just as a wealthy person of color isn’t automatically “oppressed.” Context, as Kincheloe’s critical constructivism and Butler’s performativity suggest, reveals the fluidity of power.

- Dialogue Over Dogma: Following Boghossian and hooks, prioritize open conversation over moral litmus tests. Ask questions, listen, and assume good faith, even when views differ. This builds bridges, not walls.

- Shared Humanity Over Tribalism: Inspired by hooks and Haidt, focus on common values—care, fairness, resilience—rather than pitting groups against each other. Solutions to injustice come from collaboration, not zero-sum battles.

In practice, this might look like a workplace addressing Maya’s barriers by examining hiring data and fostering inclusive policies, not just hosting struggle sessions. Or an X discussion where users debate ideas with evidence, not identity-based accusations. This framework doesn’t ignore systemic issues—it builds on the lens’s insights—but approaches them with humility, curiosity, and a commitment to unity.

Closing Thoughts

The oppressor/oppressed lens gave voice to the marginalized, but it’s not the whole story. Its binary moralism, as we’ve seen, often divides more than it heals. By embracing context, dialogue, and shared humanity, we can move toward a morality that honors complexity and fosters progress. What do you think of this approach? Share your thoughts in the comments—I’d love to hear how you navigate these issues.

Sources: Peter Boghossian’s How to Have Impossible Conversations (2019), James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose’s Cynical Theories (2020), New Discourses (https://newdiscourses.com/), Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and The Righteous Mind (2012), bell hooks’ Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), Joe L. Kincheloe’s Critical Constructivism: A Primer (2005, p. 23).

Epilogue: Reflecting on Truth and a Path Forward

This series has unpacked the oppressor/oppressed lens, a framework that shapes how we view justice and morality. We traced its roots to intersectionality and class consciousness, explored its modern misuses—from struggle sessions to dogmatic cancellations—and critiqued its limitations with insights on power, tribalism, and solidarity. The lens reveals systemic wrongs, like Maya’s workplace barriers, but its binary moralism often fuels division over dialogue.

We proposed a better way: a moral framework of context over categories, dialogue over dogma, and shared humanity over tribalism. This approach tackles injustice with nuance—think workplaces analyzing hiring data, not just moral confessions, or X debates grounded in evidence, not accusations. It honors complexity while fostering progress.

Why explore these ideas? For me, it’s about pursuing objective truth and working across divides—the only way forward, in my view. The lens’s ideology, from rigid narratives to tribal pile-ons, obscures truth and fractures us. I’m driven to seek truth through reason, as Kincheloe’s critical constructivism urges, and to bridge gaps, as hooks’ beloved community envisions. Truth and unity require tough conversations, not moral absolutes.

I invite you to reflect: How does the lens shape your world? Can we collaborate across divides? Try applying context and dialogue in your next discussion—whether at work or online. Share your thoughts in the comments. Let’s build a path forward together.

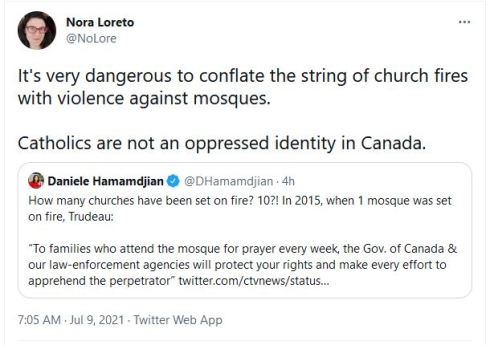

Identity politics serves to corrupt the notions of morality, common sense, and what it means to live in a society under the rule of law. This is a brief examination of a twitter thread I stumbled across about the recent cases of Catholic Churches being burnt down as misguided retaliation for the residential school system that was in place in Canada.

” SASKATOON — A former Polish Roman Catholic church in rural Saskatchewan was destroyed by fire Thursday.

The church was located near Redberry Lake, which is about 80 kilometres northwest of Saskatoon.

Lynn Swystun, who lives about a mile and a half west of the church, says she noticed smoke from her yard around 12:15 p.m. then drove to the area and discovered the church engulfed in flames.”

Now here is where it gets interesting, this is a response to the story.

Wait, what? Where exactly is the conflation happening? Damage to places of worship, in my books, is damage to places of worship. But apparently, in Nora’s world, your identity is also somehow a factor that should be used to categorize the level of violence, determining whether the violence is ‘valid’ or not.

If you’ve been with us here DWR you know that I’m not exactly the biggest supporter of organized religion and all the tomfoolery it is responsible for. But, even being the anti-religious soul that I am, I wouldn’t attempt to order and rank attacks on places of worship into ‘worthy’ and ‘less worthy’ categories.

What kind of internal moral compass is Nora going by here?

The hell? It isn’t a hate crime to burn down a place of worship because of a political/ideological motivation? And, yes the actions of the Catholic Church are indeed pretty horrible, but burning down a church is not how we express our displeasure in a nominally civilized society that values the rule of law.

Just in case if you missed it. This is the moral wasteland that much of identity politics leads to. The level of oppression Catholics face in our society is irrelevant the crime that has been committed. Burning down a church is arson. Arson is against the law, for good reason, in our society. There is no “good” or “valid” arson permissible if one wants to live in a reasonable law abiding society.

Do you see it there? The bullshit notion that there are differing levels of ‘arsonability’ based on your identity in society (of course it comes from a pronouns bio *smh*). Err no. There is no fucking way this paradigm can work if we want society as we know it to work. Past oppression does not mean a free pass when you break the law.

Is protest a part of a democratic society, absolutely. It is our civic duty to keep our political class in check and in tune with needs of the people. Arson, however, is not one of those methods that should not be considered acceptable in society as a path to change.

“The psychopath’s response to people who suffer indicates that what we recognise as morality might be grounded not simply in positive, prosocial emotions but also in negative, stressful and self-oriented ones. This is not some cuddly version of empathy, but a primitive aversive reaction that seemingly has little to do with our caring greatly for the humanity of others.

Yet what exposes our common humanity more than the fact that I become personally distressed by what happens to you? What could better make me grasp the importance of your suffering? The personal part of empathic distress might be central to my grasping what is so bad about harming you. Thinking about doing so fills me with alarm. Arguably, it’s more important that I curb my desire to harm others for personal gain than it is for me to help a person in need. Social psychology research has focused on how we’re moved to help others, but that’s led us to ignore important aspects of ethics. Psychopathy puts personal distress back in the centre of our understanding of the psychological underpinnings of morality.

The last lesson we can learn concerns whether sentimentalists or rationalists are right when it comes to interpretations of the moral deficits of psychopaths. The evidence supports both positions. We don’t have to choose – in fact, it would be silly for us to do so. Rationalist thinkers who believe that psychopaths reason poorly have zoomed in on how they don’t fear punishment as we do. That has consequences down the line in their decision making since, without appropriate fear, one can’t learn to act appropriately. But on the side of the sentimentalists, fear and anxiety are emotional responses. Their absence impairs our ability to make good decisions, and facilitates psychopathic violence.

Fear, then, straddles the divide between emotion and reason. It plays the dual role of constraining our decisions via our understanding the significance of suffering for others, and through our being motivated to avoid certain actions and situations. But it’s not clear whether the significance of fear will be palatable to moral philosophers. A response of distress and anxiety in the face of another’s pain is sharp, unpleasant and personal. It stands in sharp contrast to the common understanding of moral concern as warm, expansive and essentially other-directed. Psychopaths force us to confront a paradox at the heart of ethics: the fact that I care about what happens to you is based on the fact I care about what happens to me.”

We’ve all experienced the inner hardening, and turning away when faced with another human being in need. Of course it isn’t indicative of us being a psychopath, but the ability to realize that ethical distance is trait we all share. I realize the pain and suffering of people who are starving, but they are far away and I can turn away and ignore their suffering and get along with my life.

We’ve all experienced the inner hardening, and turning away when faced with another human being in need. Of course it isn’t indicative of us being a psychopath, but the ability to realize that ethical distance is trait we all share. I realize the pain and suffering of people who are starving, but they are far away and I can turn away and ignore their suffering and get along with my life.

Seems kinda shitty once you think about it, and the fact that most people do it doesn’t lessen the gravity of this particular ethical failure. Yet, the behaviour will persist, a dubious solution to the real life situations that run up against our moral understanding of the world.

This sort of ethical dilemma is illustrated in the series Breaking Bad. I’m almost done (two episodes left) watching Breaking Bad, and the moral path Walter White chooses to walk seems to illustrate the how muddy ‘good ethical behaviour’ gets once it hits the real word.

“To be clear, a moral injury is not a psychiatric diagnosis. Rather, it’s an existential disintegration of how the world should or is expected to work—a compromise of the conscience when one is butted against an action (or inaction) that violates an internalized moral code. It’s different from post-traumatic stress disorder, the symptoms of which occur as a result of traumatic events. When a soldier at a checkpoint shoots at a car that doesn’t stop and kills innocents, or when Walter White allows Jesse’s troublesome addict girlfriend to die of an overdose to win him back as a partner, longstanding moral beliefs are disrupted, and an injury on the conscience occurs.”

What quality makes people bounce back from a moral injury, or turn further toward questionable moral choices? We’d all like to think we belong to the class of upstanding, moral citizens – but how long does that last once the unkind vicissitudes of life go into overdrive?

My undergraduate University days were nothing like what is routinely described as the ‘University Experience’. It was a much more utilitarian experience – go to class, take notes, and then rinse and repeat the next day. Add review said notes and study as test time rolled around. The social aspect of University was pretty much all but lost on me at the time as the group of friends I had at the time did not attend. In hindsight, not having friends doing the same thing made focusing on my studies much more difficult and it extended my stay at the lovely U by a few years. Lessons learned and what not.

So, my Uni days were, to oversimplify, just highschool but harder. My real learning started or at least the path to intellectual maturity started after I earned my degree. It also helped that my partner was smart af and pushed me to become more rigorous in developing and defending my thoughts and arguments. So when I read this essay I could understand what they where saying, but couldn’t really relate to what was being said of the state of university/college campuses regarding the moral/social development of their students.

For me, finding my moral and ethical centre was quite independent of the educational process, such as it was, during my tenure at the U. Granted, of course, I was being exposed to and learning about topics that would, in the future, inform my ethical-self and boundaries, but nothing on the level which seems to happen in the US college scene. So then while reading this quote intrigued me:

“It is entirely reasonable, then, for students to conclude that questions of right and wrong, of ought and obligation, are not, in the first instance at least, matters to be debated, deliberated, researched or discussed as part of their intellectual lives in classrooms and as essential elements of their studies. “

What? Isn’t inside the classroom where the great arguments and debates should happen? I mean, it is in the university that you can hash out and grapple with the big problems with the help of professors and the knowledge that they bring and provide of the big thinkers that have grappled with these questions in the past. The university is where you can make mistakes and get nuanced feedback that will sharpen your intellectual faculties and better equip you to lead the examine life, right?

(It’s funny – none of this really happened for me – sit in class, get taught stuff, regurgitate stuff – was the order of the day). But yeah, in the formal sense, if you’re not going to university to grapple with the right and wrong questions, then why go? Getting a degree for job is nice and stuff, but attending higher education is supposed to be more than that.

Here is an excerpt from Wellmen’s take on the the state of the university experience in the US:

“The transformation of American colleges and universities into corporate concerns is particularly evident in the maze of offices, departments and agencies that manage the moral lives of students. When they appeal to administrators with demands that speakers not be invited, that particular policies be implemented, or that certain individuals be institutionally sanctioned, students are doing what our institutions have formed them to do. They are following procedure, appealing to the institution to manage moral problems, and relying on the administrators who oversee the system. A student who experiences discrimination or harassment is taught to file complaints by submitting a written statement; the office then determines if the complaint potentially has merit; the office conducts an investigation and produces a report; an executive accepts or rejects the report; and then the office ‘notifies’ the parties of the ‘outcome’.

These bureaucratic processes transmute moral injury, desire and imagination into an object that flows through depersonalised, opaque procedures that produce an ‘outcome’. Questions of character, duty, moral insight, reconciliation, community, ethos or justice have at most a limited role. US colleges and universities speak to the national argot of individual rights, institutional affiliation and complaint that dominate American capitalism. They have few moral resources from which to draw any alternative moral language and imagination.

The extracurricular system of moral management requires an ever-expanding array of ‘resources’ – counselling centres, legal services, deans of student life. Teams of devoted professionals work to help students hold their lives together. The people who support and oversee these extracurricular systems of moral management do so almost entirely apart from any coherent curricular project.

It is entirely reasonable, then, for students to conclude that questions of right and wrong, of ought and obligation, are not, in the first instance at least, matters to be debated, deliberated, researched or discussed as part of their intellectual lives in classrooms and as essential elements of their studies. They are, instead, matters for their extracurricular lives in dorms, fraternities or sororities and student activity groups, most of which are managed by professional staff. “

It seems less of an organic process, and more of a ritualized ‘thing ya do’ to start making the bucks in society. It seems like such a waste that we have strict qualifications to get and to graduate, but at the same time that we’re not challenging people, making them stretch and reform their assumptions about the world. Where else can we have the space to do such important life work?

Grab your morning coffee and enjoy your Sunday Disservice. :)

Your opinions…