You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Politics’ tag.

On January 3, 2026, the United States carried out a large-scale operation in Venezuela that resulted in the capture of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, and their transfer into U.S. custody. [1] Within hours, the story stopped being only about Maduro. It became a stress test of the West’s default assumptions about how global order actually works.

The reaction split fast and predictably: condemnation framed in the language of sovereignty and the UN Charter; applause framed in the language of liberation and justice; and, underneath both, a quieter argument about whether “international law” is a meaningful constraint—or primarily a vocabulary used to legitimize outcomes power already permits.

Two languages for one event

When a great power uses force to remove a sitting head of state and relocate him for prosecution, states and commentators typically reach for one of two languages.

The first is legal-institutional: Was this lawful? Was it authorized? What does the UN Charter permit? What precedent does it set?

The second is strategic-realist: What will it cost? Who can impose consequences? What does it deter? What does it invite?

These languages often coexist, but Venezuela forced a choice because it exposed the tension between *the claim* of a rules-governed international order and *the mechanism* by which order actually persists.

The enforceability problem

The measured point is not that international law is “fake” in every domain. A great deal of international life runs on rules that are real in practice: treaties, trade arrangements, financial compliance, aviation coordination, maritime norms, and sanctions enforcement. In those domains, rules can be highly consequential because they are tied to access, markets, and institutional membership.

But in the domain that states care about most—hard security and regime survival—international law runs into a structural limitation: there is no global sovereign with a monopoly on force. The question is not whether rules exist, but whether they bind the actors most able to ignore them.

That isn’t a rhetorical flourish. It’s the structural fact everything else sits on.

The UN can convene, condemn, and deliberate. But it cannot consistently coerce major powers into compliance. In the wake of the Maduro operation, the UN Security Council moved to meet and the UN Secretary-General warned the action set a “dangerous precedent.” [2] That may shape legitimacy and alliances. It may raise political costs. But it does not function like law inside a state, because law inside a state ultimately rests on enforceable authority.

This is why the phrase “international law” so often behaves less like binding law and more like legitimacy currency—something states spend, something rivals contest, and something that matters most when it is backed by power.

The reaction spectrum makes more sense as philosophy, not partisanship

The political reactions were not merely partisan reflexes; they were expressions of competing world-models.

Institutionalists treated the precedent as the core danger: once unilateral force becomes normalized, the world becomes easier for worse actors to imitate.

Sovereignty-first critics (especially in regions with long memories of intervention) treated it as a return to imperial patterns—regardless of Maduro’s character.

Results-first supporters treated it as overdue action against an entrenched authoritarian regime and criminal networks.

Realists treated it as a reminder that rules do not restrain actors who cannot be credibly punished.

It is possible to disagree with the operation and still accept the realist diagnosis. “This was reckless” and “this reveals how order works” are not contradictions—they’re often the same conclusion stated in different registers.

A small but telling detail: systems moved, not just speeches

One detail worth noting is that the event had immediate operational spillover beyond diplomacy: temporary Caribbean airspace restrictions and widespread flight cancellations followed, with U.S. authorities later lifting curbs. [3] That’s not a moral argument either way. It’s simply a reminder that great-power action produces real-world system effects instantly—while multilateral processes operate on a different clock.

Meanwhile, Venezuela’s internal institutions scrambled to project continuity. On January 4, 2026, reporting described Venezuela’s Supreme Court ordering Vice President Delcy Rodríguez to assume the interim presidency following Maduro’s detention. [4] Again, one can read this in legal terms or strategic terms. But it underscores the same point: the decisive moves were being made through power, institutional control, and logistics—not through international adjudication.

What Venezuela is really teaching

The strongest measured conclusion is this:

1. International law can matter as coordination and legitimacy.

2. But in hard-security conflicts, it does not function like ordinary law because enforcement is selective, especially against great powers.

3. Therefore, when Western leaders speak as though “international law” itself will constrain outcomes, they are often describing the world they want—or the world they remember—more than the world that exists.

This is the wake-up Venezuela delivers: not that rules are worthless, but that rules don’t become rules until they are paired with credible consequences. If the West wants a world that is safer for liberal societies, it must stop mistaking procedural vocabulary for strategic capacity.

What Western leaders should do differently

If “international law” is often a language of legitimacy rather than a source of enforcement, then the task for Western leaders is not to abandon norms—but to rebuild the conditions under which norms can actually hold. That requires a change in posture that is both external and internal.

First: speak honestly about interests and tradeoffs.

A rules vocabulary can be morally sincere and still strategically evasive. Western publics deserve leaders who can say, without euphemism, what outcomes matter, why they matter, and what costs we are willing to pay to secure them.

Second: re-embody Western values in our institutions, not merely our slogans.

The West is not “a place that sometimes gets things right.” It is the most successful civilizational experiment yet produced: freedom under law, pluralism, scientific dynamism, broad prosperity, and the moral insight that the individual matters. If leaders treat this as an embarrassment rather than an inheritance, they will govern as caretakers of decline.

Third: restore civic confidence by repairing the narrative infrastructure.

A civilization that teaches its own children that it is uniquely evil will not defend itself—or even understand why it should. The “mono-focused West-is-bad” story has become a kind of institutional reflex across parts of education, culture, and bureaucracy. You can reject naïve triumphalism while still insisting on civilizational honesty: that the West has flaws, committed crimes, and still produced the best lived human outcomes at scale to date.

Fourth: build capacity again—material, strategic, and moral.

Norms without capacity do not preserve peace; they invite tests. This means defense industrial readiness, energy resilience, border and migration competence, counterintelligence seriousness, and the willingness to impose costs where deterrence requires it.

Finally: treat multilateralism as a tool, not a substitute for power.

Institutions can amplify strength; they cannot conjure it. A West that wants a stable order must stop acting as though process is the engine. Process is the dashboard.

Afterword: the more polemical take

Western elites keep reaching for “international law” the way a sleepwalker reaches for the bedside table—by habit, not by sight. They speak as if naming the norm substitutes for enforcing it. But there is no authority behind it for the actors that matter most.

So the scandal isn’t disagreement about Venezuela. The scandal is that so many of our leadership classes still talk like we live in a world where legitimacy language can replace power, unity, and competence. That was a comfortable posture in a more unipolar era. It is a dangerous posture now.

In a multipolar environment, moral declarations without strength don’t preserve order. They advertise weakness. And weakness is not neutral: it invites tests.

Footnotes

[1] Reuters (Jan 3–4, 2026): reporting on the U.S. operation capturing Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores and transferring them to U.S. custody.

[2] Reuters (Jan 3, 2026): UN Security Council to meet over U.S. action; UN Secretary-General calls it a “dangerous precedent”; meeting requested with backing from Russia/China.

[3] Reuters (Jan 3, 2026): Caribbean airspace restrictions and flight cancellations following the operation; later lifted.

[4] Reuters (Jan 4, 2026): Venezuela’s Supreme Court orders Delcy Rodríguez to assume interim presidency after Maduro’s detention.

Direct Reference Links

[1] Reuters — “Mock house, CIA source and Special Forces: The US operation to capture Maduro”

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/mock-house-cia-source-special-forces-us-operation-capture-maduro-2026-01-03/

[2] Reuters — “UN Security Council to meet Monday over US action in Venezuela”

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/un-chief-venezuela-us-action-sets-dangerous-precedent-2026-01-03/

[3] Reuters — “US lifts Caribbean airspace curbs after attack on Venezuela”

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-airlines-cancel-flights-after-caribbean-airspace-closure-2026-01-03/

[4] Reuters — “Venezuela’s Supreme Court orders Delcy Rodriguez become interim president”

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/venezuelas-supreme-court-orders-delcy-rodriguez-become-interim-president-2026-01-04/

For most of my adult life, I identified as left-of-centre. I supported progressive policies on social issues, the environment, and equality. But over the past few years—especially now, at 51—I’ve found myself increasingly out of step with parts of the contemporary left. Not because my values changed, but because many of the policies being pushed today feel more disruptive than constructive. They often reshape core institutions, family structures, or economic systems without clear evidence that the changes will work long-term.

This isn’t a turn toward extremism. I still care deeply about compassion, fairness, and progress. What has changed is my tolerance for sweeping experimentation without rigorous testing. I want policy that is incremental, evidence-based, and willing to adjust when data shows something isn’t working. That’s not ideology—it’s responsibility.Seeking evidence-driven solutions isn’t inherently “right-wing.” Both sides claim to follow the data, but in practice, good policy should transcend labels. Historically, Canadian conservatism has often embodied this approach: balanced budgets, stable institutions, and pragmatic reforms that build on what already works rather than tearing systems down in pursuit of unproven theories.

Yet critics are quick to slap on labels like “Maple MAGA”—a term meant to equate any Canadian centre-right view with the most polarizing elements of U.S. Trumpism. It’s a lazy shortcut, designed to shut down conversation rather than understand it. Not every conservative is a populist firebrand. Many people—myself included—are simply tired of rapid, ideologically driven changes that risk destabilizing society without demonstrating clear benefits.

I’m not closed off. If strong evidence emerges showing that bold progressive policies genuinely improve stability, opportunity, and quality of life, I’m willing to reconsider. But right now, I see more promise in cautious, proven approaches that respect the complexity of the systems we’re trying to improve.

What about you? Have your views shifted as you’ve gained more life experience? I’m interested in real dialogue: no smears, no lazy labels, and no assumptions that a shift in perspective means abandoning core values.

For Canadians observing American politics from across the border, the U.S. conservative movement can look unusually volatile—especially after Donald Trump’s 2024 victory reinforced his influence over the Republican Party. If the Canadian Conservative Party is a “big tent,” the GOP is a sprawling, louder, and more internally divided version of the same idea. Its factions share broad goals but clash over identity, strategy, and the future of the movement.

In a recent public commentary, writer James Lindsay outlined five distinct factions competing for influence on the American right. His taxonomy is one interpretation among many, but it captures real ideological and generational tensions. For Canadians trying to understand how these divisions might shape U.S. policy, it’s a useful map.

1. Establishment Republicans: The Institutional Conservatives

These are the traditional, business-oriented conservatives—what Lindsay calls the “stodgy suit-wearing” wing. They emphasize:

• limited government

• free trade

• predictable governance

• strong national defense

For Canadians, this group resembles the Mulroney-era blue Tories: polished, institutionally minded, and cautious about populist disruption.

2. “RINO” Moderates: The Centrist Republicans

“RINO” (Republican In Name Only) is a pejorative label used by hardliners to describe moderates they see as too conciliatory or ideologically soft. Think of figures who prioritize bipartisan cooperation or resist populist rhetoric.

The Canadian parallel would be how some conservatives dismiss “Red Tories” as insufficiently committed to conservative principles. The term reflects internal policing rather than a neutral category, but it marks a real divide between ideological purists and pragmatic centrists.

3. Middle MAGA: The Populist-Pragmatic Core

Lindsay identifies Middle MAGA as the current center of gravity within the GOP. This faction emphasizes:

• patriotism

• common-sense governance

• America First policies

• civic engagement

• skepticism of foreign wars

It is largely Gen X–led and blends populist energy with practical governance. For Canadians, the closest analogue is Pierre Poilievre’s populist-but-practical conservatism: anti-elite, affordability-focused, and oriented toward achievable reforms rather than sweeping ideological overhauls.

4. The Woke Right / Post-Liberal Radicals

This faction—also described as post-liberal, paleoconservative, or national conservative—rejects classical liberalism’s emphasis on individual rights and free markets. Instead, they advocate:

• a more interventionist state

• protectionist economics

• government enforcement of cultural or religious norms

• a strong national identity

Lindsay criticizes this group for adopting tactics he associates with left-wing activism, such as purity tests and identity-based rhetoric. For Canadians, this resembles fringe nationalist or sovereigntist currents—loud, ideological, and disruptive, but not representative of mainstream conservative policy.

5. Pragmatic Neo-Establishment Republicans (e.g., DeSantis-aligned)

This faction overlaps with Middle MAGA but is distinct in its technocratic, results-oriented approach. These conservatives:

• embrace populist themes

• maintain classical liberal commitments

• prioritize policy execution and administrative competence

Lindsay uses Ron DeSantis as an example of this style: populist in tone, managerial in practice. For Canadians, this resembles the Harper-era blend of populist messaging with disciplined governance.

Where the Movement Is Heading

Lindsay predicts that the most likely future for the American right is a fusion between Middle MAGA (3) and the pragmatic neo-establishment (5). This coalition would combine populist energy with administrative competence, pulling many traditional establishment conservatives (1) along with it.

By contrast, he expects the RINO moderates (2) and the Woke Right/post-liberal radicals (4) to resist this consolidation—“kicking and screaming,” as he puts it—and potentially causing disruption from the fringes.

Why This Matters for Canada

These internal American debates have direct implications for Canadians. U.S. conservative politics influence:

• trade policy and tariffs

• energy infrastructure, including pipelines and cross-border projects

• border security and immigration coordination

• NATO and continental defense

As Trump’s second term unfolds, the balance of power among these five factions could shape everything from tariff structures to foreign aid priorities. For Canada, understanding these divisions is essential. Our closest ally and largest trading partner is navigating a period of ideological realignment—one that echoes our own debates, but on a larger, louder, and more consequential scale.

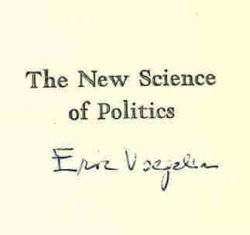

(TL;DR) Eric Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics remains one of the clearest guides to our modern disorder. It teaches that when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void—and history descends into Gnostic fantasy. Voegelin’s remedy is not new revolution but ancient remembrance: the recovery of the soul’s openness to reality.

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) was an Austrian-American political philosopher who sought to diagnose the spiritual derangements of modernity. In his 1952 classic The New Science of Politics—first delivered as the Walgreen Lectures at the University of Chicago—Voegelin proposed that politics cannot be understood as a merely empirical or procedural science. Power, institutions, and law arise from a deeper spiritual ground: humanity’s participation in transcendent order. When societies lose awareness of that participation, they fall into ideological dreams that promise salvation through human effort alone. The book is therefore both a critique of modernity and a call to recover the classical and Christian understanding of political reality (Voegelin 1952, 1–26).

1. The Loss of Representational Truth

Every stable society, Voegelin argued, “represents” its members within a larger order of being. In ancient civilizations and medieval Christendom, political authority symbolized this participation through myth, ritual, and law that acknowledged a reality beyond human control. The ruler was not a god but a mediator between the temporal and the eternal.

Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the monk Joachim of Fiore reimagined history as a self-unfolding divine drama in which humanity itself would bring about the final age of perfection. With this shift, Western consciousness began to “immanentize the eschaton”—to relocate ultimate meaning inside history rather than in its transcendent source. Out of this inversion grew the modern ideologies of progress (Comte, Hegel), revolution (Marx), and race (National Socialism), each promising earthly redemption through planning and will (Voegelin 1952, 107–132).

For Voegelin, the loss of representational truth meant that governments no longer reflected humanity’s place in divine order but instead projected utopian images of what they wished reality to be. Politics ceased to be the articulation of truth and became the engineering of salvation.

2. Gnosticism as the Modern Disease

Voegelin identified the inner structure of these movements as Gnostic. Ancient Gnostics sought hidden knowledge that would liberate the soul from an evil world; their modern successors, he said, sought knowledge that would liberate humanity from history itself. “The essence of modernity,” Voegelin wrote, “is the growth of Gnostic speculation” (1952, 166).

He listed six recurrent traits of the Gnostic attitude:

- Dissatisfaction with the world as it is.

- Conviction that its evils are remediable.

- Belief in salvation through human action.

- Assumption that history follows a knowable course.

- Faith in a vanguard who possess the saving knowledge.

- Readiness to use coercion to realize the dream.

From medieval millenarian sects to twentieth-century totalitarian states, these traits form a single continuum of spiritual rebellion: the attempt to perfect existence by abolishing its limits.

3. The Open Soul and the Pathologies of Closure

Against the Gnostic impulse stands the open soul—the philosophical disposition that accepts the “metaxy,” or the in-between nature of human existence. We live neither wholly in transcendence nor wholly in immanence, but within the tension between them. The philosopher’s task is not to resolve that tension through fantasy or reduction but to dwell within it in faith and reason.

Political science, therefore, must be noetic—concerned with insight into the structure of reality—not merely empirical. A society’s symbols, institutions, and laws can be judged by how faithfully they articulate humanity’s participation in divine order. Disorder, Voegelin warned, begins not with bad policy but with pneumopathology—a sickness of the spirit that refuses reality’s truth. “The order of history,” he wrote, “emerges from the history of order in the soul.”

Empirical data can measure economic growth or electoral results, but it cannot measure spiritual health. That requires awareness of being itself.

4. Liberalism’s Vulnerability and the Way of Recovery

Voegelin saw liberal democracies as historically successful yet spiritually precarious. By reducing political order to procedural legitimacy and rights management, liberalism risks drifting into the nihilism it opposes. When public life forgets its transcendent foundation, freedom degenerates into relativism, and pluralism becomes mere fragmentation.

Still, Voegelin’s outlook was not despairing. His proposed remedy was anamnesis—the recollective recovery of forgotten truth. This is not nostalgia but awakening: the rediscovery that human beings are participants in an order they did not create and cannot abolish. The recovery of the classic (Platonic-Aristotelian) and Christian understanding of existence offers the only durable antidote to ideological apocalypse (Voegelin 1952, 165–190).

To “keep open the soul,” as Voegelin put it, is to resist every movement that promises paradise through force or theory. The alternative is the descent into spiritual closure—an ever-recurring temptation of modernity.

5. Contemporary Resonance

Voegelin’s analysis remains uncannily prescient. Today’s ideological battles—whether framed around identity, technology, or climate—often echo the same Gnostic pattern: discontent with the world as it is, belief that perfection lies just one policy or re-education campaign away, and impatience with reality’s resistance. The post-modern conviction that truth is socially constructed continues the old dream of remaking existence through will and language.

Voegelin’s warning cuts through our century as clearly as it did the last: when politics replaces truth with narrative and transcendence with activism, society repeats the ancient heresy in secular form. The cure, as ever, is humility before what is—the recognition that order is discovered, not invented.

References

Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Glenn. 2003. Transcendence and History: The Search for Ultimacy from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Sandoz, Ellis. 1981. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glossary of Key Terms

Anamnesis – Recollective recovery of forgotten truth about being.

Gnosticism – Revolt against the tension of existence through claims to saving knowledge that masters reality.

Immanentize the eschaton – To locate final meaning and salvation within history rather than beyond it.

Metaxy – The “in-between” condition of human existence, suspended between immanence and transcendence.

Noetic – Pertaining to intellectual or spiritual insight into reality’s order.

Pneumopathology – Spiritual sickness of the soul that closes itself to transcendent reality.

Representation – The symbolic and political articulation of a society’s participation in transcendent order.

Poland’s ascent to a $1 trillion economy in September 2025 marks a remarkable transformation. Emerging from the wreckage of Soviet control, Poland has become one of Europe’s fastest-growing economies over the past three decades. With GDP growth projected at 3.2 percent for 2025, unemployment near 3 percent (harmonized), and inflation moderating to 2.8 percent in August, it demonstrates resilience and steady progress.

Canada, with a nominal GDP of roughly $2.39 trillion, is richer in absolute terms but faces weaker dynamics: growth forecasts of just 1.2 percent, unemployment climbing to 7.1 percent in August, and persistent concerns over productivity and rising public debt. The contrast raises an important question: which elements of Poland’s success can Canada responsibly adapt to its own very different circumstances?

1. Manufacturing Capacity and Industrial Resilience

Poland’s economy has benefited from retaining a strong industrial base, especially in automotive, machinery, and technology supply chains closely integrated with Germany. This foundation has provided steady export growth and employment, while limiting excessive reliance on fragile overseas supply chains.

Canada, by contrast, has seen its manufacturing share of GDP shrink over decades as industries relocated or hollowed out. While Canada cannot replicate Poland’s role as a mid-cost hub inside the EU, it could adapt the principle: incentivize the repatriation or expansion of high-value sectors (e.g., EV manufacturing, critical minerals processing, aerospace). Strategic tax credits, infrastructure investment, and streamlined permitting could restore resilience and provide middle-class employment.

Lesson for Canada: industrial renewal need not mean autarky, but building domestic capacity in key sectors reduces vulnerability to shocks — as Poland’s stability during recent European crises shows.

2. Immigration Policy and Integration Capacity

Poland has pursued a relatively selective immigration system, prioritizing labor market fit and manageable inflows. While Poland remains relatively homogeneous (Eurostat estimates about 98% ethnic Polish in 2022), its policy has focused on ensuring newcomers integrate into economic and cultural life. The result has been high employment among migrants and limited social disruption compared with some Western European peers.

Canada, by contrast, accepts large inflows — even after scaling back targets to 395,000 permanent residents in 2025 — and faces housing pressures and uneven integration outcomes. Canada’s homicide rate (2.27 per 100,000 in 2022) is higher than Poland’s (0.68), though crime is shaped by many factors beyond immigration. Still, rapid population growth without infrastructure, housing, and language capacity has heightened social strains.

Lesson for Canada: immigration policy should balance humanitarian goals with absorptive capacity. Emphasizing labor alignment, regional settlement, and language proficiency — as Poland has done — would help ensure inflows strengthen productivity while minimizing stress on housing and services.

3. Cultural Continuity and Heritage as Assets

Poland has paired modernization with deliberate protection of its cultural identity. The restoration of Kraków and Warsaw not only preserves heritage but fuels a thriving tourism sector. National traditions, rooted in Catholicism for many Poles, have also informed family policy (e.g., child benefits) and provided a sense of cohesion during rapid economic change.

Canada’s pluralism differs fundamentally, and it cannot — and should not — mimic Poland’s religious or cultural model. Yet Canada can still learn from the broader principle: treating heritage and shared narratives as economic and social assets rather than obstacles. Investments in Indigenous landmarks, Francophone culture, and historic architecture could enrich tourism, foster pride, and strengthen cohesion. Likewise, family-supportive policies (parental leave, child benefits, flexible work arrangements) are essential as Canada faces declining fertility and an aging workforce.

Lesson for Canada: cultural preservation and demographic support are not nostalgic luxuries — they can reinforce economic stability and social cohesion.

4. Fiscal Prudence and Monetary Autonomy

Poland’s choice to retain the zloty rather than adopt the euro preserved monetary flexibility. Combined with relatively conservative fiscal policies (public debt at about 49% of GDP in 2024, well below EU ceilings), this has allowed Poland to respond to crises with agility while maintaining competitiveness.

Canada already benefits from its own currency, but fiscal expansion has pushed federal debt above 65% of GDP. While Canada’s wealth affords greater borrowing room, long-term sustainability requires discipline. Poland’s experience suggests that debt caps, counter-cyclical saving, and careful monetary coordination can preserve resilience without stifling growth.

Lesson for Canada: fiscal credibility is itself an economic asset. Setting clearer debt-to-GDP targets and enforcing discipline would strengthen Canada’s ability to weather global volatility.

Conclusion

Poland’s trajectory is not without challenges. It faces demographic decline, reliance on EU subsidies, and governance controversies that Canada would not wish to replicate. But its achievements underscore a vital truth: prosperity need not mean sacrificing resilience, identity, or cohesion.

For Canada, the actionable lessons are clear:

-

rebuild key industries,

-

align immigration with integration capacity,

-

invest in heritage and families,

-

and re-anchor fiscal policy in prudence.

Adapted to Canadian realities, these reforms could help lift growth closer to 3 percent, reduce unemployment, and restore a sense of national momentum.

References

-

International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Database, October 2025.

-

Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey, August 2025.

-

Eurostat. Population Structure and Migration Statistics, 2022–2025.

-

OECD. Economic Outlook: Poland and Canada, 2025.

-

World Bank. World Development Indicators, 2024–2025.

-

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Homicide Statistics, 2022.

-

National Bank of Poland. Annual Report, 2024.

-

Government of Canada. Immigration Levels Plan 2025–2027.

Frantz Fanon’s seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, provides a framework for understanding decolonization as a radical, often violent, restructuring of society, which some activists in Canada have adopted to challenge the foundations of Western civilization. Fanon argues that decolonization is inherently disruptive, stating, “Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a program of complete disorder” (Fanon, 1963, p. 36). In the Canadian context, this rhetoric is echoed in calls to dismantle institutions, reject Eurocentric histories, and prioritize Indigenous frameworks over established systems. A recent example is the controversy surrounding the Ontario Grade 9 Math Curriculum, where the inclusion of anti-racism and decolonization language—such as claims that mathematics has been used to “normalize racism”—led to significant backlash and eventual removal of such content (Global News, 2021). While presented as a pursuit of justice, this approach often amplifies societal fractures, pitting Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups against one another. By framing Canada’s history solely as a colonial oppression narrative, activists risk fostering resentment and division, undermining the shared societal cohesion necessary for a functioning democracy. This strategy aligns with Fanon’s vision of upending the status quo but ignores the complexities of Canada’s multicultural fabric, where reconciliation and cooperation have been attempted through dialogue and policy, however imperfectly.

The activist push for decolonization in Canada, inspired by Fanon’s ideas, often employs a rhetoric of moral absolutism that vilifies Western institutions while ignoring their contributions to global stability and progress. Fanon writes, “The colonial world is a Manichaean world” (Fanon, 1963, p. 41), casting the colonizer and colonized in stark, irreconcilable opposition. In Canada, this binary is reflected in demands to erase symbols of Western heritage—such as statues of historical figures or traditional educational curricula—in favor of an exclusively Indigenous narrative. For instance, Ryan McMahon’s 12-step guide to decolonizing Canada proposes radical changes, including the return of land to Indigenous peoples and reallocating 50% of natural resource export revenues to Indigenous nations (CBC Radio, 2017). Such proposals, while framed as reconciliation, can be seen as divisive and impractical by many Canadians, fostering a sense of cultural erasure among non-Indigenous Canadians while creating unrealistic expectations of systemic overhaul. By framing decolonization as a zero-sum conflict, activists inadvertently sow discord, weakening the social contract that binds diverse communities. Instead of fostering unity, this tactic mirrors Fanon’s call for a radical break, which may destabilize the very society it seeks to reform, playing into a broader narrative of internal collapse rather than constructive change.

Ultimately, the application of Fanon’s decolonization framework in Canada serves as a divisive tool that threatens the stability of Western societies by prioritizing ideological purity over pragmatic coexistence. Fanon asserts, “For the colonized, life can only spring up again out of the rotting corpse of the colonizer” (Fanon, 1963, p. 93), a statement that implies destruction as a prerequisite for renewal. In Canada, this translates into activist strategies that reject compromise, demanding sweeping societal transformations without acknowledging the complexities of a nation built on diverse contributions. A historical example is the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, where concerns over Indigenous land rights led to a 10-year moratorium on the project, delaying economic development and highlighting how decolonization efforts can significantly impact community relations and national progress (Berger, 1977). By weaponizing decolonization to vilify Western values, these efforts risk eroding the democratic principles—freedom, rule of law, and pluralism—that have enabled Canada’s relative stability. Rather than unifying society around shared goals, this approach fuels polarization, aligning with a broader agenda to dismantle Western institutions from within under the guise of justice, leaving little room for reconciliation or mutual progress.

Key Citations

- The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

- Ontario removes anti-racism text from math curriculum preamble

- Ryan McMahon’s 12-step guide to decolonizing Canada

- Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland: Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry

- Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Proposals

- Decolonization at BC’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner

- Catholic church north of Edmonton destroyed in fire

- School curriculum in Canada disputes view of math as objective

Your opinions…