You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘History’ category.

The Age of Discovery was not a morality play. It was a capability leap. Between the late 1400s and the 1600s, Europeans built a durable system of oceanic navigation, mapping, and logistics that connected continents at scale. That system reshaped trade, ecology, science, and eventually politics across the world.

None of this requires sanitizing what came with it. Disease shocks, conquest, extraction, and slavery were not side notes. They were part of the story. The problem is what happens when modern retellings keep only one side of the ledger. When “discovery” is taught as a synonym for “oppression,” history stops being inquiry and becomes a single moral script.

What the era achieved

The Age of Discovery solved practical problems that had limited long-range sea travel: how to travel farther from coasts, how to fix position reliably, and how to represent the world in a form that could be used again by the next crew.

Routes mattered first. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and helped establish the sea-route logic that linked the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean world. That made long voyages less like stunts and more like repeatable corridors.

Maps made it scalable. In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller’s map labeled “America” and presented the newly charted lands as a distinct hemisphere in European cartography. In 1569, Mercator’s projection made course-setting more practical by letting navigators plot constant bearings as straight lines. These were not aesthetic achievements. They were infrastructure for a global system.

Instruments and technique followed. Mariners relied on celestial measurement, and Europeans benefited from earlier work in the Islamic world and medieval transmission routes that carried astronomical knowledge and instrument development into Europe. This is worth stating plainly because it strengthens the real point: the Age of Discovery was not magic. It was the synthesis and scaling of knowledge into a logistical machine.

Finally, there was proof of global integration. Magellan’s expedition, completed after his death by Juan Sebastián del Cano, achieved the first circumnavigation. Whatever moral judgments one makes about the broader era, this was a genuine expansion of what humans could do and know.

What it cost

The same system that connected worlds also carried catastrophe.

Indigenous depopulation after 1492 was enormous. Scholars debate the causal mix across regions, but the scale is not seriously in dispute. One influential synthesis reports a fall from just over 50 million in 1492 to just over 5 million by 1650, with Eurasian diseases playing a central role alongside violence, displacement, and social disruption.

The transatlantic slave trade likewise expanded into a vast engine of forced migration and brutal labor. Best estimates place roughly 12.5 million people embarked, with about 10.7 million surviving the Middle Passage and arriving in the Americas. These are not “complications.” They are central moral facts.

And the Columbian Exchange, often simplified into “new foods,” was a sweeping biological and cultural transfer that included crops and animals, but also pathogens and ecological disruption. It permanently altered diets, landscapes, and power.

A reader can acknowledge all of that and still resist a common conclusion: that the entire era should be treated as a civilizational stain rather than a mixed human episode with world-changing outputs.

The Exchange is the model case for a full ledger

A fact-based account has to hold two truths at once.

First, the biological transfer had large, measurable benefits. Economic historians have argued that a single crop, the potato, can plausibly explain about one-quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900. That is a civilizational consequence, not an opinion.

Second, the same transoceanic link that moved calories also moved coercion and disease. That is not a footnote. It is part of the mechanism.

The adult position is not denial and not self-flagellation. It is proportionality.

Where “critical theory” helps, and where it can deform

Critical theory is not one thing. In the broad sense, it names a family of approaches aimed at critique and transformation of society, often by making power, incentives, and hidden assumptions visible. In that role, it can correct older triumphalist histories that ignored victims and treated conquest as background noise.

The failure mode appears when the lens becomes total. When domination becomes the only explanatory variable, achievement becomes suspect simply because it is achievement, and complexity is treated as apology. The story turns into prosecution.

One can see the tension in popular history writing. Howard Zinn’s project, for example, explicitly recasts familiar episodes through the eyes of the conquered and the marginalized. That corrective impulse can be valuable. But critics such as Sam Wineburg have argued that the method often trades multi-causal history for moral certainty, producing a “single right answer” style of interpretation rather than a discipline of competing explanations. The risk is that students learn a posture instead of learning judgment.

A parallel point is worth making for Indigenous-centered accounts. Works like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s are explicit that “discovery” is often better described as invasion and settler expansion. Even when one disagrees with some emphases, the existence of that challenge is healthy. It forces the older story to grow up.

But there is a difference between correction and replacement. Corrective history adds missing facts and voices. Replacement history insists there is only one permissible meaning.

Verdict: defend the full ledger

Western civilization does not need to be imagined as flawless to be defended as consequential and often beneficial. The Age of Discovery expanded human capabilities in navigation, cartography, and global integration. It also produced immense suffering through disease collapse, coercion, and slavery.

A healthy civic memory holds both sides of that ledger. It teaches the costs without denying the achievements, and it refuses any ideology that demands a single moral story as the price of belonging.

References

Bartolomeu Dias (1488) — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bartolomeu-Dias

Recognizing and Naming America (Waldseemüller 1507) — Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/collections/discovery-and-exploration/articles-and-essays/recognizing-and-naming-america/

Mercator projection — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/science/Mercator-projection

Magellan and the first circumnavigation; del Cano — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-Magellan

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Sebastian-del-Cano

Mariner’s astrolabe and transmission via al-Andalus — Mariners’ Museum

European mariners owed much to Arab astronomers — U.S. Naval Institute (Proceedings)

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1992/december/navigators-1490s

Indian Ocean trade routes as a pre-existing global network — OER Project

https://www.oerproject.com/OER-Materials/OER-Media/HTML-Articles/Origins/Unit5/Indian-Ocean-Routes

Indigenous demographic collapse (1492–1650) — British Academy (Newson)

Transatlantic slave trade estimates — SlaveVoyages overview; NEH database project

https://legacy.slavevoyages.org/blog/brief-overview-trans-atlantic-slave-trade

https://www.neh.gov/project/transatlantic-slave-trade-database

Potato and Old World population/urbanization growth — Nunn & Qian (QJE paper/PDF)

Click to access NunnQian2011.pdf

Critical theory (as a family of theories; Frankfurt School in the narrow sense) — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/

Zinn critique: “Undue Certainty” — Sam Wineburg, American Educator (PDF)

https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2012-2013

Indigenous-centered framing (as a counter-story) — Beacon Press (Dunbar-Ortiz)

https://www.beacon.org/An-Indigenous-Peoples-History-of-the-United-States-P1164.aspx

In the world of advocacy and human rights, consistency is more than just a virtue—it’s what gives our principles real meaning. Recently, a comment on social media highlighted a familiar pattern: certain voices who are vocal about one cause may fall silent when similar struggles appear in a different context. It’s a reminder that if we want justice to truly be just, it must be blind to who is involved—applying the same standards to all people, regardless of race, creed, or background.

This isn’t about slamming any particular group; it’s about encouraging all of us to reflect on the importance of consistency. When we advocate for human rights, it’s crucial that we do so across the board. If a group of protesters in one country deserves our solidarity, then those in another country risking their lives for similar ideals deserve it too.

In short, “justice” in quotes should indeed be blind. Not in the sense of ignoring the nuances of each situation, but in the sense of applying our moral standards fairly and universally. By doing so, we strengthen the credibility of our advocacy and remind the world that human rights aren’t selective—they’re for everyone.

Find that tweet inspiration for this post here.

- Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB, 2006; expanded 2015): Provided $100/month per child under 6 (later $160), plus $60/month for ages 6–17. This universal payment went to all families, delivering $1,200–$1,920 annually per young child to help with living or childcare costs—directly benefiting low-income households without means-testing stigma.

- Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB, 2007; precursor to Canada Workers Benefit): A refundable credit topping up earnings for low-wage workers (up to $1,000 for singles, $2,000 for families), reducing the “welfare wall” and making work more rewarding.

- Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP, 2008): Government matching grants up to 300% plus bonds up to $1,000/year for low-income families with disabled members.

- Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA, 2009): Allowed tax-free growth and withdrawals, helping low-income Canadians build emergency savings.

- Children’s Fitness and Arts Tax Credits (2006–2014 expansions): Up to $500–$1,000 per child, made partially refundable for low-income families.

Other measures included enhanced GST/HST credits, public transit tax credits, caregiver credits, and increased funding for First Nations child welfare. These weren’t trickle-down theories—they were direct transfers and credits that disproportionately aided lower-income groups.Measurable Impact: Poverty and Low-Income Rates DeclinedStatistics Canada data corroborates the effectiveness of these policies:

- Child poverty under the Market Basket Measure (MBM, Canada’s official poverty line since 2018) showed improvement during the Harper years, with overall poverty at 14.5% in 2015 (the benchmark year for federal targets).

- Low-income rates using the after-tax Low Income Measure (LIM-AT) fell from around 13–14% in the mid-2000s to 11.2% by 2015.

- After-tax incomes for the bottom income quintile rose approximately 17% from 2006 to 2015, driven by tax cuts and benefits.

While poverty dropped more sharply after 2015 with the introduction of the Canada Child Benefit (which built on and reformed some Harper-era programs), the Harper government laid groundwork with direct supports that helped stabilize and reduce low-income rates amid the 2008 global recession.Why the Myth Persists—and Why It’s MisleadingCritics often prefer expansive government-run programs (e.g., national daycare) over direct cash to families, viewing the latter as insufficient.

- Original X thread and policy list: https://x.com/GreatBig_Sea/status/1982121517665137029

- Statistics Canada Dimensions of Poverty Hub (MBM and LIM trends): https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/topics-start/poverty

- Government of Canada background on Harper-era family measures: https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2015/07/today-parents-get-child-care-payments-harper-government-1003359.html

- Wikipedia summary of Universal Child Care Benefit (with sources): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Child_Benefit

In the end, actions speak louder than slogans. The Harper record shows a commitment to practical support for low-income families—not indifference.

(TL;DR) – Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France warned that abstract ideals, once severed from tradition, devour the civilization that birthed them. Against the arrogance of rationalist utopia, Burke offers a philosophy of gratitude: reform through inheritance, freedom through reverence, and wisdom through time.

Edmund Burke (1729–1797), the Irish-born British statesman and philosopher, published Reflections on the Revolution in France in November 1790 as an open letter to a young Frenchman. Written before the Revolution’s worst excesses, the work is less a history than a prophetic warning against uprooting inherited institutions in the name of abstract rights.

At a time when Enlightenment rationalists sought to rebuild society from first principles, Burke defended the British constitution not as perfect but as the tested fruit of centuries of moral and political experience. Against the revolutionary attempt to remake society on metaphysical blueprints, he argued that true political wisdom rests in “prescription” (inheritance), “prejudice” (habitual virtue), and the moral imagination that clothes authority in reverence and restraint. Reflections thus became the founding text of modern conservatism, grounding politics in humility before the slow wisdom of civilization (Burke 1790, 29–55).

1. The Organic Constitution versus the Mechanical State

Burke likens a healthy commonwealth to a living organism whose parts grow together over time. The British settlement of 1688, which balanced liberty and order, exemplified reform through continuity—“a deliberate election of light and reason,” not a clean slate.

The French revolutionaries, by contrast, treated the state as a machine to be disassembled and reassembled according to geometric principles. They dissolved the nobility, confiscated Church lands, and issued assignats—paper money backed only by revolutionary will. Burke foresaw that such rationalist tinkering would require force to maintain: “The age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded.” The predictable end, he warned, would be military dictatorship—the logic of abstraction enforced by bayonets (Burke 1790, 56–92).

2. The Danger of Metaphysical Politics

The Revolution’s fatal error, Burke argued, was to govern by “the rights of man” divorced from the concrete rights of Englishmen, Frenchmen, or any particular people. These universal abstractions ignore circumstance, manners, and the “latent wisdom” embedded in custom.

When the revolutionaries dragged Queen Marie Antoinette from Versailles to Paris in October 1789, Burke saw not merely a political humiliation but a civilizational collapse: “I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult.” The queen, for him, symbolized a moral order that elevated society above brute appetite. Once such symbols are desecrated, civilization itself is imperiled (Burke 1790, 93–127).

3. Prescription, Prejudice, and the Moral Imagination

For Burke, rationality in politics is not the isolated reasoning of philosophers but the accumulated judgment of generations. “Prescription” gives legal and moral title to long possession; to overturn it is theft from the dead. “Prejudice,” far from being ignorance, is the pre-reflective moral instinct that makes virtue habitual—“rendering a man’s virtue his habit,” Burke wrote, “and not a series of unconnected acts.”

In his famous image of the “wardrobe of a moral imagination,” Burke insists that society requires splendid illusions—chivalry, ceremony, religion—to clothe power in dignity and soften human passions. Strip away these garments and you are left with naked force and the “swinish multitude.” Culture, in his view, is not ornament but armor for civilization (Burke 1790, 128–171).

4. Prophecy Fulfilled and the Path of Prudence

Events soon vindicated Burke’s warnings: the Reign of Terror, Napoleon’s rise, and the wars that consumed Europe. Yet Reflections is not an “I told you so” but a manual for political health. Burke accepts reform as necessary but insists that it must proceed “for the sake of preservation.” The statesman’s duty is to repair the vessel of society while it still sails, not to smash it in search of utopia.

Reverence for the past and distrust of untried theory are not cowardice but prudence—the recognition that civilization is a fragile inheritance, easily destroyed and seldom rebuilt (Burke 1790, 172–280).

5. Burke’s Enduring Lesson

Burke’s insight extends far beyond the French Revolution. His critique applies wherever abstract moralism seeks to erase inherited forms—whether through revolutionary ideology, technocratic social engineering, or the cultural purism of modern movements that prize purity over continuity. The temptation to rebuild society from scratch persists, but Burke reminds us that order is not manufactured; it is cultivated.

In an age still haunted by ideological utopias, Burke’s prudence is an act of intellectual piety: to love what we have inherited enough to reform it carefully, and to mistrust those who promise perfection by destruction.

References

Burke, Edmund. 1790. Reflections on the Revolution in France, and on the Proceedings in Certain Societies in London Relative to that Event. London: J. Dodsley.

Glossary of Key Terms

Assignats – Revolutionary paper currency secured on confiscated Church property; rapid depreciation fueled inflation.

Latent wisdom – Practical knowledge embedded in customs and institutions, inaccessible to abstract reason.

Moral imagination – The faculty that clothes abstract power in elevating symbols and sentiments.

Prejudice – Pre-reflective judgment formed by habit and tradition; for Burke, a source of social cohesion.

Prescription – Legal and moral title acquired through uninterrupted possession over time.

Swinish multitude – Derisive term for the populace once traditional restraints are removed.

Why do societies slide toward tyranny when they pursue utopia? (TL;DR)

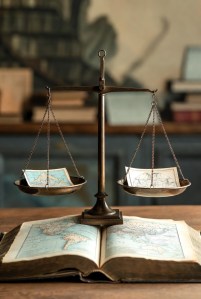

The Scales of Society argues that the real divide in politics isn’t left versus right, but realism versus idealism. When truth yields to belief, coercion follows. From communism and fascism to modern moral crusades, history warns that abandoning objective reality tips civilization toward totalitarianism. The balance must be restored—anchored in realism, humility, and truth.

In the landscape of political philosophy, metaphors serve as intellectual scaffolding—structures that help us grasp dynamics too intricate for direct depiction. The familiar political compass, with its left–right and liberty–authority axes, sketches ideological positions but fails to reveal the deeper fracture driving modern polarization. A more illuminating image is that of a balance scale. Its crossbar represents philosophical realism—the recognition of an objective reality—while the suspended pans embody the idealist extremes of communism and fascism. This model captures not just polarization but the gravitational descent into totalitarianism that occurs when societies abandon reality for utopia.

The Core Divide: Realism vs. Idealism

Realism begins with the premise that reality exists independently of human will or perception. The wall remains whether one believes in it or not, and collision has consequences indifferent to ideology. This external order imposes limits: progress requires trade-offs, and perfection is impossible. The realist accepts these constraints, submitting theories to verification through evidence, reason, law, and experience. Responsibility and competence—not vision or zeal—earn authority.

Idealism inverts this relationship. It treats reality as a projection of consciousness, imperfect but malleable. If perception shapes the world, then changing minds can remake existence. Truth becomes what society collectively affirms. This impulse, when politicized, leads toward social constructivism and, inevitably, coercion: those who refuse to affirm the “truth” must be re-educated or silenced. A contemporary example can be seen in gender ideology, where subjective identity claims are enforced as social fact through compelled speech and institutional conformity. The point is not about gender per se but about the pattern: belief overriding biology through social pressure rather than persuasion.

The Platonic ideal—perfect, transcendent, and abstract—becomes the new absolute. The imperfect, tangible world must be reshaped until it conforms. Once utopia is imagined as possible, coercion becomes inevitable, for someone must ensure that all comply with the ideal.

The Scale and Its Balance

The realist crossbar allows for movement and balance. One may lean left toward egalitarianism, right toward hierarchy and tradition, or find equilibrium between the two. Disputes are adjudicated by verifiable standards: evidence, empirical data, or, for the religious, revelation interpreted through disciplined exegesis. Justice is blind, authority is earned, and failure prompts responsibility rather than revolution.

From that crossbar hang the chains leading to the pans—communism on the left, fascism on the right. Each represents idealism in a different costume. Descent is gradual, a shimmy downward from realism into partial idealism, then freefall into extremism. The pans have no centers: in a world of pure ideals, moderation cannot hold.

Communism imagines a belief-driven utopia—re-educate humanity into “species-being” beyond property or conflict, and paradise will emerge. Fascism demands obedience to a mythic hierarchy—sacrifice self for the community’s glory, and unity will prevail. Both subjugate reality to ideology: when facts resist, facts are crushed. From the perspective of either pan, the realist crossbar appears as the enemy’s support beam. Each seeks to destroy it, believing that only by breaking the balance can truth be realized.

Polarization and the Descent

As tension mounts, the scale begins to swing. Idealists radicalize when realism resists persuasion—utopia seems attainable but for “obstructionist” constraints. In frustration, anti-fascism justifies communism; anti-communism, fascism. The center thins as factions define themselves by opposition rather than truth. The political becomes existential: the other side must be destroyed, not debated. The mechanisms of verification—law, science, journalism, reasoned discourse—collapse under pressure. Force replaces evidence; propaganda replaces persuasion.

History confirms the pattern. The twentieth century saw communism outlast fascism, not because it was less violent but because it sold coercion through promises of emancipation. Fascism, with its naked appeal to dominance, exhausted itself; communism cloaked tyranny in moral idealism. Both ended in mass graves.

Left and Right: The Limits of Tolerance

The realism–idealism axis cuts deeper than the traditional left–right divide. The left tends toward anti-traditionalism and radical egalitarianism, seeking liberation through the dissolution of hierarchy and norm. The right inclines toward tradition and hierarchy, valuing stability and inherited order. Each contains wisdom and danger.

Tradition carries epistemological weight: customs that survive generations have proven utility—Chesterton’s fence stands until one understands why it was built. Yet tradition can ossify, defending arbitrariness or prejudice. Egalitarianism corrects injustice but becomes destructive when it denies the functional necessity of hierarchy. Even lobsters, as Jordan Peterson once observed, form dominance orders; structure is not oppression but biology. When hierarchy is treated as sin and equality as salvation, society drifts from realism into moral mythology.

The Peril of Idealism

Idealism’s danger is not merely its optimism but its refusal to recognize limits. When imagination detaches from reality, coercion rushes in to bridge the gap. The ideal cannot fail; only people can. Those who resist must be “re-educated” or “deprogrammed.” What begins as moral vision ends as total control.

The cure is humility—a willingness to let facts instruct rather than ideology dictate. Repentance, in the philosophical sense, means returning from illusion to reality, subordinating theory to evidence and loving wisdom without claiming omniscience. Realism requires courage: to see, to accept, and to act within the bounds of what is possible.

Lessons from the Twentieth Century and Beyond

The horrors of the last century—gulags, purges, and genocides—were not aberrations but logical conclusions of idealism unmoored from realism. Communism and fascism both promised transcendence from the human condition; both delivered degradation. Today, similar impulses reappear in moralized movements on left and right that treat disagreement as heresy and consciousness as the final battleground. These are not new phenomena but recycled idealisms—different symbols, same metaphysics.

In an era of manufactured crises and moral crusades, the scales remind us: cling to the crossbar. Only realism—anchored in evidence, bounded by humility, and guided by verifiable truth—permits tolerance, adaptation, and progress. When the crossbar breaks, society plunges into the abyss, and one pan’s triumph becomes delusion for all.

References

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1951.

- Burke, Edmund. Reflections on the Revolution in France. London: J. Dodsley, 1790.

- Chesterton, G.K. The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic. London: Sheed & Ward, 1929.

- Lewis, C.S. The Abolition of Man. London: Oxford University Press, 1943.

- Lindsay, James. Left and Right with Society in the Balance. New Discourses Lecture, 2025.

- Peterson, Jordan B. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Toronto: Random House, 2018.

- Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge, 1945.

- Voegelin, Eric. The New Science of Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Your opinions…