You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘History’ category.

Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil remains one of the twentieth century’s most incisive dissections of moral failure. Published in 1963, the book emerged from Arendt’s firsthand reporting on the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, a mid-level Nazi bureaucrat whose role in orchestrating the deportation of millions of Jews to death camps defined the Holocaust’s logistical horror. Expectations ran high for a portrait of unalloyed monstrosity, yet Arendt delivered something far more unsettling: a portrait of profound ordinariness. Eichmann was no ideological zealot or sadistic fiend, but a careerist adrift in clichés and administrative jargon, driven by ambition and an unswerving commitment to hierarchy. From this unremarkable figure, Arendt forged her enduring concept of the banality of evil, a framework that exposes how systemic atrocities arise not from demonic intent but from the quiet abdication of critical thought.

The Trial That Shattered Expectations

Arendt arrived in Jerusalem as a correspondent for The New Yorker, tasked with chronicling the prosecution of Eichmann, the architect of the Nazis’ “Final Solution” in practice if not in origin. What she witnessed defied the trial’s dramatic staging. Eichmann, perched in his glass booth, projected not menace but mediocrity. He droned on in a flat, bureaucratic patois, insisting his actions stemmed from dutiful obedience rather than personal malice. “I never killed a Jew,” he protested, as if the euphemism absolved the machinery he oiled. This was no Iago or Macbeth, but a joiner par excellence: shallow, conformist, and utterly unable to grasp the human weight of his deeds. Arendt’s revulsion crystallized mid-trial, in her notebooks, where she first sketched the phrase that would redefine her legacy. The banality of evil was born not from Eichmann’s depravity, but from his incapacity for reflection—a thoughtlessness that rendered him complicit in genocide without the depth to comprehend it.

Unpacking the Banality: From Demonic to Mundane

At its core, the banality of evil upends the romanticized view of wickedness as inherently profound or radical. Evil, Arendt contended, often manifests as banal: the work of unimaginative souls who drift through conformity, failing to interrogate their roles in larger systems. Eichmann exemplified this through his linguistic sleight of hand. He evaded the raw truth of extermination, speaking instead of “transportations” and “processing,” terms that sanitized slaughter into spreadsheet entries. Hatred played little part; obedience, careerism, and social inertia sufficed. The terror lay in his normalcy. As Arendt observed, evil flourishes not among isolated monsters but in societies where individuals relinquish moral judgment to rules, authorities, or routines. This banality, she later clarified, arises from an active refusal to exercise judgment, transforming ordinary people into cogs of catastrophe.

Arendt wove this insight into her broader philosophical tapestry, where thinking emerges as the essential moral safeguard. In the Socratic tradition, genuine thought demands we question the rightness of our actions, bridging the gap between knowledge and ethics. Eichmann’s failure was not intellectual deficiency alone, but a willful suspension of this faculty—substituting slogans and protocols for scrutiny. She identified thoughtlessness as totalitarianism’s hallmark, a regime that trains citizens to obey without asking why, eroding the pluralistic dialogue vital to human freedom. Against this, Arendt posited “natality,” the human capacity for birth and renewal, as a counterforce: each new beginning compels us to initiate thought, disrupting entrenched banalities.

The Firestorm of Controversy

Arendt’s conclusions ignited immediate backlash. Critics, including Jewish intellectuals like Gershom Scholem, accused her of exonerating Eichmann and scapegoating victims by critiquing the Jewish councils’ coerced cooperation with Nazi demands. Her dispassionate tone struck many as callous, diluting the Holocaust’s singularity into a lesson in human frailty. Yet Arendt sought neither absolution nor minimization; her aim was diagnostic. Evil in bureaucratic modernity, she argued, stems from collective complicity, not just from fanatics. The ordinary enablers—those who obey without question—sustain the system as surely as the architects. This polemic endures, with debates persisting over whether Arendt undervalued antisemitism’s visceral role, but her thesis has proven resilient, outlasting the initial fury.

Philosophical Stakes: Redefining Moral Agency

Arendt’s innovation lies in relocating moral responsibility from sentiment to cognition. Agency begins not with feeling but with thought: the deliberate act of judging actions against universal principles. This aligns her work with deeper epistemic concerns, where unexamined beliefs pave the way for ethical collapse. Without the courage to probe “Is this true? Is this right?”, reasoning devolves into rote compliance. The banality of evil thus warns of disengagement in any apparatus—state, corporation, or ideology—where “just following orders” masks profound harm. In an age of institutional sprawl, her call to vigilant judgment remains a bulwark against the mindless perpetuation of injustice.

Lessons for Our Fractured Age: Thoughtlessness in Ideological Currents

Arendt’s framework offers stark lessons amid the ascendance of critical social constructivism, woke Marxism, and gender ideology—movements that, in their zealous conformity, risk replicating the very thoughtlessness she decried. Critical social constructivism, with its insistence that reality bends to narrative power, echoes Eichmann’s euphemistic detachment: truths are “constructed” not discovered, fostering a relativism where evidence yields to doctrinal fiat. Proponents, often ensconced in academic silos, propagate this without interrogating its epistemic costs, much as Arendt saw totalitarianism erode pluralistic inquiry. The result? A moral landscape where dissent is pathologized as “harm,” inverting Socratic dialogue into inquisitorial purity tests.

Woke Marxism, blending identity politics with class warfare rhetoric, amplifies this banality through performative allegiance. What begins as equity advocacy devolves into bureaucratic rituals—DEI mandates, cancel campaigns—that demand uncritical adherence, sidelining the reflective judgment Arendt deemed essential. Critics from leftist traditions note how this mirrors the “administrative massacres” she analyzed, where ideological slogans supplant ethical scrutiny, enabling everyday cruelties under the guise of progress. Ordinary adherents, like Eichmann’s clerks, comply not from malice but from careerist inertia, blind to the dehumanization they abet.

Gender ideology presents perhaps the most poignant parallel, transforming biological verities into fluid “affirmations” via sanitized language that obscures irreversible interventions. Global market projections for sex reassignment surgeries, valued at $3.13 billion in 2025, anticipate reaching $5.21 billion by 2030, underscoring this commodified banality: procedures framed as “care” evade the long-term harms to minors, much as Nazi logistics masked extermination. Voices like J.K. Rowling invoke Arendt directly, highlighting how euphemisms prevent equating these acts with “normal” knowledge of human development. Shallow conformity here—fueled by fear of ostracism—propagates misogynistic erosions of women’s spaces and youth safeguards, all without the depth to confront consequences.

Arendt’s antidote is uncompromising: reclaim thinking as moral praxis. In our screen-lit caves, where algorithms curate consensus and ideologies brook no doubt, we must cultivate epistemic humility—the willingness to question, to pluralize, to judge anew. Only thus can we arrest banality’s creep, ensuring that goodness, radical in its depth, prevails over evil’s empty routine. Thoughtlessness is not fate; it is choice. And in choosing reflection, we honor the dead by fortifying the living against their shadows.

References

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (For concepts of natality and action.)

Berkowitz, R. (2013). “The Banality of Hannah Arendt.” The New York Review of Books, June 6. (On ongoing debates of her thesis.)

Mordor Intelligence. (2024). Sex Reassignment Surgery Market Size, Trends, Outlook 2025–2030. Retrieved October 5, 2025, from https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/sex-reassignment-surgery-market.

Rowling, J. K. [@jk_rowling]. (2024, December 28). “This astounding paper reminds me of Hannah Arendt’s The Banality of Evil…” [Post]. X. https://x.com/jk_rowling/status/1873048335193653387.

Scholem, G. (1964). “Reflections on Eichmann: The Trial of the Historian.” Encounter, 23(3), 25–31. (Open letter critiquing Arendt’s portrayal.)

Villa, D. (1996). Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (For connections to Socratic thinking and totalitarianism.)

When political violence erupts, it often looks random — a lone extremist, a protest that gets out of hand, or a clash between two angry groups. But much of what we’re seeing today, in both the United States and Canada, is not random at all. It is part of a deliberate strategy that activists call dialectical warfare — and it is tearing at the heart of our democratic societies.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk and the furious conservative backlash that followed are not isolated events. They are part of a larger spiral of violence and reaction, one that radicals hope will end with the collapse of our current system. To understand how, we need to unpack an old idea: the dialectic.

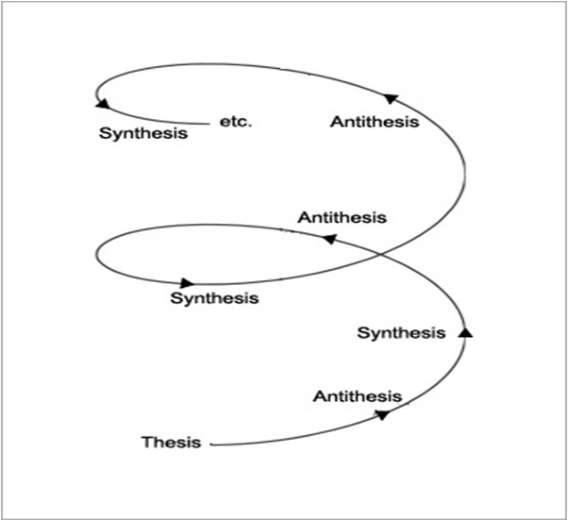

What is the Dialectic?

The word “dialectic” comes from philosophy, specifically the German thinker Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in the early 1800s. At its simplest, the dialectic is a way of describing how history moves forward through conflict.

- Thesis: the current system or status quo.

- Antithesis: the force that challenges it.

- Synthesis: a new system that emerges after the clash.

For Hegel, this was a way of understanding history as a story of progress. Marx later took this idea and made it the foundation of his revolutionary theory. For him, history was about class struggle: workers against capitalists. Capitalism, he argued, would eventually collapse under its contradictions and give way to communism.

The key point is this: conflict isn’t a bug in the system — it’s the engine of history.

From Philosophy to Political Activism

Fast forward to today. Many left-wing activists, consciously or not, operate with a dialectical mindset. They believe that society advances through conflict and breakdown, not peaceful debate.

That means chaos, division, and even violence can be seen as useful. If enough conflict is stirred up, the system will be forced to reveal its flaws, overreact, and eventually collapse — clearing the way for something new.

This isn’t conspiracy theory. Activist manuals, writings from radical groups, and historical revolutionary movements all share this logic. The goal is not stability. The goal is destabilization.

Dialectical Warfare Today

Dialectical warfare is what happens when activists deliberately create or amplify conflict to destabilize society. Here’s how it works in practice:

- Provocation: Protests or acts of violence designed to draw a harsh reaction.

- Overreaction: Authorities or opponents respond too aggressively, confirming the activists’ narrative.

- Crisis: The clash erodes faith in institutions and convinces people the system doesn’t work.

- Escalation: Each cycle of conflict moves society further up the spiral toward collapse.

It’s not about winning the argument. It’s about breaking the system so that something “better” (usually some form of socialist utopia) can be built on the ruins.

The Charlie Kirk Case

The recent assassination of Charlie Kirk shows this dynamic clearly. For the radical Left, the act of violence itself was a shock designed to destabilize. But what mattered more was the reaction.

Conservatives in power, outraged and furious, began employing the same tools that had once been used against them: censorship, cancel culture, and efforts to silence left-wing voices. In their anger, they began shredding the same democratic norms — free speech, due process, respect for law — that they had once fought to defend.

From the perspective of dialectical warfare, this is a victory for the radicals. The point was never just to kill one man. The point was to provoke an overreaction that would weaken the credibility of conservative leaders, make democratic institutions look fragile, and drive polarization even deeper.

Why This is Dangerous

Every time conservatives react by copying the authoritarian tactics of the Left, they confirm the radicals’ worldview. They prove that democracy is a sham, that free speech is a lie, and that the system is doomed.

This is exactly what the activist Left wants. They welcome conservative overreach, because it accelerates the collapse of the old order. The tragedy is that in fighting back, the right risks becoming what it hates: reactionary, authoritarian, and destructive of the very freedoms it claims to defend.

Lessons from History

We have seen this before. In the 20th century, totalitarian movements from Communism in Russia to fascism in Germany thrived on dialectical conflict. They used street violence, political assassinations, and manufactured crises to polarize society. Each overreaction by their opponents brought them closer to power.

The idea is seductive: “This system is broken. Only radical action can save us.” But the results are always catastrophic. Millions died under regimes that promised utopia and delivered tyranny.

A Simple Analogy

Think of democracy like a family car. It’s not perfect — sometimes it breaks down, sometimes it needs repairs. Activists practicing dialectical warfare are not trying to fix the car. They are trying to crash it on purpose, believing that after the wreck, they’ll be able to build a perfect new vehicle.

But history shows that after the crash, what you usually get is not a better car — it’s a dictatorship.

The Dialectical Spiral at Work

To make this crystal clear, here’s how activists see the spiral — and what really happens:

| Stage | Activist Left’s View | What Actually Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Provocation | Stir conflict (riots, violence, incendiary rhetoric) to expose “systemic oppression.” | Communities destabilize; trust erodes. |

| Reaction | Force conservatives into authoritarian overreach. | Free speech and rule of law weaken; institutions lose credibility. |

| Crisis | Show that democracy and capitalism can’t solve the conflict. | Cynicism deepens; polarization hardens. |

| Escalation | Push society up the spiral toward “revolution and utopia.” | Cycle repeats, leading not to utopia but greater instability. |

Why We Must Resist

The activists’ dream of a communist utopia is a fantasy that has failed every time it’s been tried. But their strategy of dialectical warfare is very real — and very effective at breaking societies apart.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk and the conservative overreaction it triggered are a warning. If we allow ourselves to be baited into authoritarian responses, we are not saving democracy — we are digging its grave.

The only way forward is to resist the spiral: to defend free speech, uphold the rule of law, and refuse to play into the radicals’ hands. Otherwise, we will all be dragged into the chaos they long for, and the freedoms that make Western society unique will vanish in the wreckage.

References

- Hegel, G.W.F. The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807).

- Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Communist Manifesto (1848).

- Arendt, H. On Violence (1970).

- Popper, K. The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945).

- Contemporary coverage: Reuters, Associated Press, Fox News (Sept. 2025) – reporting on the assassination of Charlie Kirk and ensuing political fallout.

In a recent post, I criticized Orange Shirt Day as a ritualized form of national self-loathing. That critique stands — but I have to admit I fell into a trap myself: I repeated elements of the story of Phyllis Webstad without checking the details.

Her now-famous account is that, as a six-year-old, she was sent to St. Joseph’s Mission, where her brand-new orange shirt was taken away on her first day. That image — the innocent child stripped of her identity by cruel authority — became the symbolic foundation of Orange Shirt Day and, in turn, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. It is powerful. It moves people. It creates policy.

But is it literally true in every detail? The answer is murkier than most Canadians are led to believe. Critics such as Rodney Clifton, a former residential school worker and researcher, have pointed out that Webstad attended St. Joseph’s when it was functioning as a student residence — not a traditional residential school — and that she attended public school in Williams Lake. Others note that staff were often Indigenous lay workers rather than the stereotypical “nuns with scissors.” Even Webstad herself has described that year as one of her “fondest memories,” a detail that vanishes from the public retelling.

In other words: the story has been simplified, polished, and repeated until it no longer represents the whole truth. This is how narratives work. They take a fragment of reality and expand it into myth — and then the myth becomes untouchable. Questioning it, or even pointing out inconsistencies, can make one a “denier” or a “deplorable.”

That is the lesson here. I fell for the narrative too, because it was convenient. It had emotional force. It seemed to explain everything at a glance. But truth — especially historical truth — is rarely that neat.

If Canadians want real reconciliation, it has to be based on facts, not fables. We do Indigenous people no favors by sanctifying selective memories while ignoring the messy, complicated realities of reserve life, family breakdown, and the mixed legacy of institutions like St. Joseph’s. Nor do we honor our own country by allowing symbolic stories to become instruments of guilt rather than prompts for genuine understanding.

References

-

Orange Shirt Society: Phyllis’ Story — orangeshirtday.org

-

Rodney Clifton, They Would Call Me a ‘Denier’ — C2C Journal

- UBC Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, About Orange Shirt Day — irshdc.ubc.ca

- Troy Media, Clifton & Rubenstein, The Truth behind Canada’s Indian Residential Schools — troymedia.com

This feature length investigative documentary, about the aftermath of the Kamloops mass grave deception, was produced by Simon Hergott and Frances Widdowson. The backdrop is the March 30 talk that Frances Widdowson gave in Powell River about “Uncovering the Grave Error at Kamloops and its Relationship to the [Powell River] Name Change and UNDRIP”. Hergott and Widdowson use the issues raised in the talk to explore a number of aspects of the deception: claims about “missing children”, a lack of journalistic objectivity, and the misleading use of Ground Penetrating Radar. The role played by the Aboriginal Industry – a group of mostly non-indigenous lawyers and consultants – in instigating grievances to divert funds away marginalized communities is also examined.

The British Empire, for all its flaws, wielded its vast influence as a decisive instrument in dismantling the global scourge of slavery—a system that violated human dignity on a global scale. By the late 18th century, Britain’s economic and naval dominance positioned it uniquely to challenge the transatlantic slave trade, which it had once profited from immensely. The 1807 Slave Trade Act, driven by relentless abolitionist campaigns from figures like William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, outlawed the trade across the empire, striking a blow at the economic arteries of slavery.1 This was no mere moral posturing: Britain’s West Africa Squadron, deployed from 1808, patrolled the Atlantic, intercepting slave ships and liberating over 150,000 enslaved Africans by 1860.2 Yet the squadron’s operations were not without contradiction—many of the “liberated” were later conscripted into naval service or settled in British colonies under paternalistic regimes.

Behind these legislative shifts stood a groundswell of popular activism—thousands of petitions, boycotts of slave-grown sugar, and the mobilization of dissenting religious groups, particularly the Quakers. As J.R. Oldfield has shown, Britain’s anti-slavery effort marked one of the earliest examples of coordinated mass politics in a liberal democracy.3 This popular moral awakening fueled legislative change but faced resistance from powerful interests, particularly in the colonies. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which emancipated nearly 800,000 enslaved people across British territories, was a monumental step, but it came with caveats—planters were compensated handsomely, while freed individuals received no reparations and faced exploitative “apprenticeship” systems.4 Abolition, in this context, was less a moral epiphany than a negotiated dismantling of a profitable institution.

Britain’s abolitionist zeal extended outward, forcing other nations—such as France, Spain, and Brazil—to curtail their own slave trades through a combination of treaties, naval pressure, and economic leverage. The 1841 Quintuple Treaty bound several major European powers to suppress the transatlantic trade, demonstrating Britain’s capacity to turn moral authority into diplomatic influence.5 This was less about universal brotherhood than about asserting moral and geopolitical superiority over rivals. At home and abroad, Britain leveraged its economic clout—offering trade incentives or threatening sanctions—to coerce reluctant powers into compliance.

However, abolition did not signal the end of coerced labor; rather, it marked a transition to new forms of economic exploitation. Indentured labor, particularly from India and China, was recruited under harsh conditions and deployed across the empire to fuel plantation economies. Critics have rightly argued that this was “a new system of slavery” in all but name, replicating colonial hierarchies under the guise of freedom.6

The British Empire’s crusade against slavery, while imperfect, reshaped the global moral landscape, proving that imperial might could be harnessed for transformative ends. Its abolitionist policies rippled across the Americas, Africa, and beyond, hastening the decline of legalized slavery worldwide. By the mid-19th century, the empire’s relentless naval patrols and diplomatic arm-twisting had rendered the transatlantic trade increasingly untenable. Yet this legacy is no hagiography: Britain’s earlier profiteering from slavery and its post-abolition labor practices expose a hypocrisy that tempers its triumphs. Nonetheless, the empire’s unparalleled capacity to enforce change—through law, force, and influence—demonstrates a singular truth: no other power of the era could have so decisively tilted the scales against a centuries-old institution. The British Empire, for better or worse, was the fulcrum on which the global fight against slavery pivoted.

Footnotes

- Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery. Cambridge University Press, 2009. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abolition/9780521606592 ↩

- “The West Africa Squadron.” The National Archives, UK. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/atlantic-world/west-africa-squadron/ ↩

- Oldfield, J.R. Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilisation of Public Opinion against the Slave Trade, 1787–1807. Manchester University Press, 1995. https://manchester.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7228/manchester/9780719038570.001.0001/upso-9780719038570 ↩

- “Slavery Abolition Act 1833.” UK Parliament. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/tradeindustry/slavetrade/ ↩

- Huzzey, Richard. Freedom Burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain. Cornell University Press, 2012. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801451089/freedom-burning/ ↩

- Tinker, Hugh. A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas 1830–1920. Oxford University Press, 1974. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/a-new-system-of-slavery-9780195600749 ↩

Your opinions…