You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Philosophy’ category.

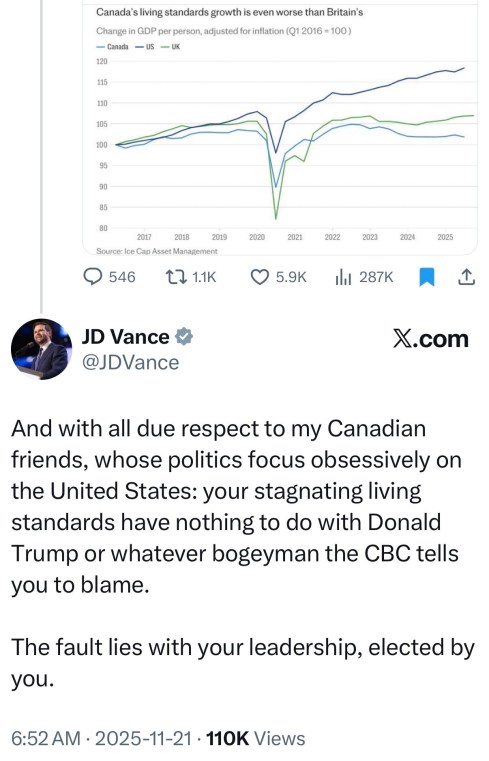

Canada finds itself at a crossroads. In recent years, per capita GDP growth has stalled, productivity remains sluggish, and housing, healthcare, and infrastructure face mounting pressure. These trends have prompted urgent debate about the causes of stagnation, ranging from global economic shifts and demographic aging to domestic policy decisions. Among commentators, JD Vance recently sparked attention with pointed critiques of Canada’s immigration policies and multicultural model, framing them as principal contributors to declining living standards. Beyond the immediate provocation, his intervention highlights a deeper question: how should Canadians assess responsibility for the state of their economy?

Immigration, Policy Choices, and Economic Outcomes

Canada’s foreign-born population now stands at approximately 23 percent, the highest in the G7, reflecting a sharp rise over the past decade. This increase was accelerated by post-pandemic labor shortages and policy decisions prioritizing high-volume admissions. While immigration is a crucial driver of population growth and labor supply, recent evidence indicates that integration has lagged, particularly for newcomers with credentials or skills mismatched to domestic demand. Unemployment rates among recent immigrants are approximately twice those of Canadian-born workers, and overall productivity growth has remained below historical trends.

These outcomes underscore a key point: while external factors including global commodity cycles, trade dynamics, and U.S. policy affect Canada’s economy, domestic decisions regarding immigration volume, infrastructure investment, and skills integration exert primary influence over living standards. The choice to expand immigration without simultaneously scaling capacity for integration, housing, and healthcare has consequences that voters ultimately authorize at the ballot box.

Stoic Lessons for Civic Responsibility

Confronted with these structural and policy realities, Canadians might feel tempted to externalize blame to markets, foreign governments, or pundits. Here, the Stoic philosophers offer timeless guidance. Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations: “You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” Epictetus similarly asserted: “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.” These principles demand that citizens distinguish between factors within their control and those beyond it, focusing energy on the former.

Stoicism is not a creed of passivity. It insists on rigorous self-examination and deliberate action. In Canada’s context, this means acknowledging the consequences of policy choices and recognizing that solutions—whether adjusting immigration strategy, improving integration programs, or investing in productivity-enhancing infrastructure—lie within domestic capacity.

Pathways to Renewal

Practical measures aligned with these principles include:

- Aligning immigration targets with absorptive capacity: Recent adjustments to temporary resident admissions, reducing projected numbers by approximately 43 percent, illustrate the potential for recalibration.

- Prioritizing skill-aligned integration: Investing in credential recognition, language training, and targeted labor placement can ensure that new arrivals contribute effectively to productivity.

- Strengthening domestic infrastructure and services: Housing, healthcare, and transportation require proportional investment to match demographic growth.

- Informed civic engagement: Voting with awareness of policy consequences is fundamental to maintaining democratic accountability and ensuring long-term economic stability.

By taking responsibility, Canadians act in accordance with Stoic precepts: focusing on what they can control rather than scapegoating external forces. The challenge is not merely economic—it is moral and civic. Prosperity depends as much on deliberate collective action as on external circumstance.

Conclusion

Canada’s stagnating living standards are the product of complex factors, yet domestic choices remain decisive. While commentary from external observers like JD Vance may provoke discomfort, the underlying lesson is clear: sovereignty entails responsibility, and agency begins at home. To confront stagnation, Canadians must embrace candid assessment of policy outcomes, deliberate reform, and disciplined civic engagement. In the words of Seneca: “We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” Facing the realities we have constructed—and acting to improve them—is the first step toward renewal.

References

- Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey, 2025. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data

- Government of Canada. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada: Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-parliament-immigration.html

- Marcus Aurelius. Meditations. Trans. Gregory Hays, 2002.

- Epictetus. Enchiridion. Trans. Elizabeth Carter, 1758.

- Seneca. Letters from a Stoic. Trans. Robin Campbell, 2004.

Glossary

- Per Capita GDP: The average economic output per person, often used as a measure of living standards.

- Productivity: Output per unit of input; a key driver of sustainable economic growth.

- Integration Programs: Policies and services designed to help immigrants participate effectively in the labor market and society.

- Absorptive Capacity: The ability of a system (economy, infrastructure, institutions) to accommodate growth without adverse effects.

- Stoicism: Philosophical framework emphasizing rational control over one’s mind and actions rather than external circumstances.

In a culture that mistakes comfort for flourishing and validation for character, Stoicism returns us to a harder and older truth: the sole good is virtue. Everything else—wealth, health, reputation, even life itself—is ultimately indifferent.

The Stoics inherited from Socrates and Plato the four cardinal virtues and declared them jointly sufficient for eudaimonia (the Greek term for the only life genuinely worth living). They are:

1. Wisdom (phronēsis)

The knowledge of what is truly good, bad, and neither.

Wisdom is not cleverness or data accumulation—it is the steady ability to judge correctly in concrete circumstances. Without wisdom, every other virtue collapses into blind habit, impulsiveness, or self-deception.

2. Courage (andreia)

Not the absence of fear but the disciplined refusal to let fear govern action.

Stoic courage shows itself in the quiet endurance of chronic pain, in speaking truth to power, in confronting injustice, and in facing death without hysteria or despair.

3. Justice (dikaiosynē)

The social virtue par excellence: giving every person what is owed—including those we dislike.

Justice expresses itself as honesty, fairness, kindness, and civic responsibility. A life without justice is predatory even when outwardly respectable.

4. Temperance (sōphrosynē)

Mastery of appetite and impulse.

Temperance is the power to say “this is enough” when desire—whether for food, sex, status, stimulation, or outrage—demands more. Without temperance, genuine freedom is impossible.

Why These Four Alone Matter

The Stoics argued, and lived, a radical proposition: virtue is both necessary and sufficient for the good life. External goods can be stripped away in an afternoon—Zeno’s fortune confiscated in Cyprus, Seneca and Epictetus exiled by Rome, Marcus Aurelius’s children taken by disease—yet none of these losses corrupted their character.

Their serenity, dignity, and usefulness endured because their excellence depended on nothing outside their prohairesis, their moral and rational faculty.

In this sense, Stoicism is not ancient self-help but a philosophical engineering of the soul.

Modern Evidence Confirms the Ancient Claim

Long-term psychological research repeatedly finds that the best predictors of life satisfaction, longevity, and emotional stability are not wealth, fame, or intelligence but traits that map directly onto the Stoic virtues:

- Conscientious self-control → temperance

- Warm, dependable relationships → justice

- Resilience under stress → courage

- Reflective, accurate judgment → wisdom

The Grant Study, the Terman cohort, and the Harvard Study of Adult Development all converge on a simple conclusion: character, not circumstance, is the foundation of lasting well-being.

How to Train the Virtues Today

You don’t “add” virtue like a supplement. You train it the way an athlete trains muscle: through deliberate, repeated action under resistance.

Wisdom

- Keep a decision journal.

- Each night ask: “Where did I misjudge good and bad today?”

- Test impressions against reason, not emotion.

Courage

- Practice voluntary discomfort: public speaking, difficult conversations.

- Fear shrinks when approached, not avoided.

Justice

- Use the dichotomy of roles. In every interaction ask: “What does my role as human being, citizen, parent, or colleague require?”

- Then do it, regardless of mood.

Temperance

- Set bright-line rules: no phone in the first hour of the day, one plate of food, no gossip.

- Desire obeys precedent.

Progress in Stoicism is measured not by emotional uplift but by this single question:

“Would I act the same way if no one ever found out and the outcome were guaranteed to be unpleasant?”

Virtue is revealed in what you do when excellence is costly.

Master these four virtues and you will lack nothing essential. Neglect them, and no wealth, therapy, or acclaim will save you from living a hollow life. This is not ancient opinion. It is observable, repeatable fact.

References

- George E. Vaillant, Triumphs of Experience: The Men of the Harvard Grant Study (Harvard University Press, 2012).

- Lewis Terman et al., Genetic Studies of Genius (Stanford University Press, 1925–1959).

- Robert Waldinger & Marc Schulz, The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness (Simon & Schuster, 2023).

- Julia Annas, The Morality of Happiness (Oxford University Press, 1993) — for classical virtue ethics and Stoic moral psychology.

- A.A. Long, Hellenistic Philosophy (University of California Press, 1986).

- Massimo Pigliucci, How to Be a Stoic (Basic Books, 2017) — modern interpretation and practice.

Glossary of Key Terms

Eudaimonia — A flourishing or fully realized human life; more than happiness, closer to “living excellently.”

Phronēsis — Practical wisdom; the ability to judge rightly.

Andreia — Courage; the discipline of confronting fear and difficulty.

Dikaiosynē — Justice; moral and social responsibility toward others.

Sōphrosynē — Temperance; self-mastery and moderation.

Prohairesis — The rational, moral faculty that governs choice and intention in Stoic psychology.

Indifferents — External conditions (health, wealth, status) that are neither good nor bad in themselves.

The Stoics taught that excess corrupts both the soul and the body politic. Seneca warned that chasing boundless expansion courts ruin — true prosperity lies not in defiance of limits, but in living in accordance with nature’s measure. Marcus Aurelius similarly counseled restraint, urging us to act within the bounds of reason and accept the limits placed upon us. Applied to governance, this means a nation — like an individual — must assess its capacities before inviting more mouths to the table.

Canada’s recent immigration trajectory betrayed this principle. In 2023, the country added more than 1.27 million people — an annual growth rate of roughly 3.2 percent, driven overwhelmingly by international migration. (Statistics Canada) Over just a few years, the population climbed from under 39 million to over 41 million.

For years, permanent-resident targets hovered near 500,000, and temporary resident classes — students, workers, etc. — swelled. By 2025, however, disturbing strains were showing: housing shortages, rent and price inflation, pressure on health services, and signs of wage stress.

These were not speculative risks. Empirical analyses from bodies such as the Bank of Canada and CMHC correlate rapid population inflows with housing-market pressure. Public opinion followed suit. By late 2025, polling indicated that nearly two-thirds of Canadians considered even the then-reduced target for permanent residents (395,000) too high; roughly half held consistently negative views on immigration, not out of xenophobia, but from perceived stress on infrastructure and housing.

Recognizing this, Ottawa has begun to recalibrate. In its 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan, released publicly, the government committed to 395,000 permanent residents in 2025, then reducing to 380,000 in 2026 and 365,000 in 2027. (Canada) Even more significantly, temporary resident targets dropped: from 673,650 new TRs in 2025 to 516,600 in 2026, with further moderation planned. (Canada)

The demographic effects are already materializing. As of mid-2025, Canada’s estimated population growth slowed to 0.9 percent year-over-year, according to RBC Economics, with non-permanent residents making up a smaller share. (RBC) This slowdown itself validates the Stoic critique of overreach — a moment of reckoning for policy driven by expansion rather than equilibrium.

This retreat is welcome, but it remains reactive. From a Stoic perspective, reactive virtue is still virtue, but prudence demands more: a wisdom that designs policy proactively, not merely corrects after crisis. A Stoic polity would have matched immigration flows to real, measurable capacity long ago — gauging housing pipelines, healthcare strain, wage effects, and social cohesion.

Immigration in moderation enriches: it brings talent, innovation, and human flourishing. But unmoored from institutional capacity, it sows fragility, inequality, and resentment.

Going forward, Canada needs to institutionalize sophrosyne — the classical virtue of temperance and self-mastery. Targets should be set not by political fantasy or corporate lobbying, but by clear metrics: housing completions, per-capita infrastructure strain, healthcare wait-lists, and social stability.

The recent dialing back is a start. But true Stoic governance demands that moderation becomes a structural norm, not just a temporary correction. Only then can the polity live in accord with nature — virtuous, resilient, and enduring.

References

- Government of Canada, 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan. Permanent resident targets: 395,000 (2025), 380,000 (2026), 365,000 (2027). (Canada)

- Canada.ca, Government of Canada reduces immigration. Temporary resident reductions, projected decline in temporary population by 445,901 in 2025. (Canada)

- RBC Economics, Canada’s population growth slows… — mid-2025 year-over-year growth of 0.9%, share of non-permanent residents falling. (RBC)

- Statistics Canada, Population estimates, Q4 2024. International migration accounted for 98.5% of growth in Q4 2024. (Statistics Canada)

- CIC News, 2026-2028 Immigration Levels Plan will include new measures… — TR targets for 2026: 385,000 quoted, among other reductions. (CIC News)

- CIBC Thought Leadership, Population-growth projections… — analysis of visa expiry, outflows, and the challenge of non-permanent resident accounting. (cms.thoughtleadership.cibc.com)

Glossary of Key Terms

| Term | Meaning / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sophrosyne | A classical Greek virtue (especially important to Stoics): moderation, temperance, self-control, and harmony with nature. In this context, it means setting immigration policy in proportion to real capacity. |

| Non-Permanent Resident (NPR) | Individuals in Canada on temporary visas: students, temporary foreign workers, etc. Not permanent residents or citizens. |

| Permanent Resident (PR) | Someone who has been granted permanent residency in Canada: not a citizen yet, but has the right to live and work permanently. |

| Levels Plan / Immigration Levels Plan | The Canadian government’s multi-year plan setting targets for new permanent and temporary immigrant admissions. |

| Absorptive Capacity | The realistic capacity of a country (or region) to accommodate newcomers without undue strain: infrastructure, housing, healthcare, labour market, social services. |

| Reactive Virtue vs. Proactive Wisdom | In Stoic terms: responding wisely after the fact (reactive) is good, but better is anticipating and designing policy with foresight (proactive). |

In the Stoic tradition, Marcus Aurelius reminds us in Meditations that the soul finds balance not by bending the world to its desires, but by living in harmony with the rational order that shapes it. Both essays—The Scales of Society and The Horseshoe’s Convergence—speak powerfully to this truth. When we trade reality for utopian dreams, we don’t advance; we regress. Realism, seen through a Stoic lens, is the practice of knowing what’s within our control—our judgments, our virtues—and what isn’t: the stubborn facts of nature and history. To pursue idealism as if the world must yield to our will is to fight against nature itself. Epictetus would call this a form of slavery to externals—an endless, exhausting battle to remake what cannot be remade. The metaphors of the scale and the curve become lessons in humility, urging us to weigh our convictions not by how righteous they feel, but by how true they are.

The danger of extremes, as both essays show, comes from losing that grounding in reality. The far left and far right don’t meet by coincidence; they curve toward each other under the same gravitational pull of unchecked passion over reason. Stoicism teaches that the will, when misdirected, can turn virtue into vice. The search for purity—whether egalitarian or hierarchical—often becomes self-righteousness, and self-righteousness turns easily into cruelty. Seneca warned that anger devours its host first, and here we see that on a societal scale: politics consumed by outrage, discourse replaced by denunciation, and myth elevated over evidence. The “horseshoe” is more than a metaphor—it’s a mirror reflecting our inner collapse when moral certainty replaces humility. The more we cling to our certitudes, the less we see of truth. In that blindness, we reproduce the very coercion we claim to oppose. Stoicism reminds us that true power is never about conquering others—it’s about mastering our own thoughts and reactions.

Yet the Stoic path is not one of despair but of quiet renewal. We can rebuild the crossbar of realism through daily discipline—by anchoring ourselves in what is, not what we wish would be. As the essays conclude, tolerance doesn’t survive through ideological victory but through shared respect for evidence and for limits. That’s a civic form of amor fati—a love of fate—that turns polarization into friction that sharpens rather than burns. When we learn to accept what’s beyond our control and focus on the integrity of our own actions, the scales find balance again, the horseshoe stays open, and reason’s republic endures. Not by force, and not by fury, but by quiet fidelity to the logos that connects us all.

(TL;DR) Eric Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics remains one of the clearest guides to our modern disorder. It teaches that when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void—and history descends into Gnostic fantasy. Voegelin’s remedy is not new revolution but ancient remembrance: the recovery of the soul’s openness to reality.

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) was an Austrian-American political philosopher who sought to diagnose the spiritual derangements of modernity. In his 1952 classic The New Science of Politics—first delivered as the Walgreen Lectures at the University of Chicago—Voegelin proposed that politics cannot be understood as a merely empirical or procedural science. Power, institutions, and law arise from a deeper spiritual ground: humanity’s participation in transcendent order. When societies lose awareness of that participation, they fall into ideological dreams that promise salvation through human effort alone. The book is therefore both a critique of modernity and a call to recover the classical and Christian understanding of political reality (Voegelin 1952, 1–26).

1. The Loss of Representational Truth

Every stable society, Voegelin argued, “represents” its members within a larger order of being. In ancient civilizations and medieval Christendom, political authority symbolized this participation through myth, ritual, and law that acknowledged a reality beyond human control. The ruler was not a god but a mediator between the temporal and the eternal.

Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the monk Joachim of Fiore reimagined history as a self-unfolding divine drama in which humanity itself would bring about the final age of perfection. With this shift, Western consciousness began to “immanentize the eschaton”—to relocate ultimate meaning inside history rather than in its transcendent source. Out of this inversion grew the modern ideologies of progress (Comte, Hegel), revolution (Marx), and race (National Socialism), each promising earthly redemption through planning and will (Voegelin 1952, 107–132).

For Voegelin, the loss of representational truth meant that governments no longer reflected humanity’s place in divine order but instead projected utopian images of what they wished reality to be. Politics ceased to be the articulation of truth and became the engineering of salvation.

2. Gnosticism as the Modern Disease

Voegelin identified the inner structure of these movements as Gnostic. Ancient Gnostics sought hidden knowledge that would liberate the soul from an evil world; their modern successors, he said, sought knowledge that would liberate humanity from history itself. “The essence of modernity,” Voegelin wrote, “is the growth of Gnostic speculation” (1952, 166).

He listed six recurrent traits of the Gnostic attitude:

- Dissatisfaction with the world as it is.

- Conviction that its evils are remediable.

- Belief in salvation through human action.

- Assumption that history follows a knowable course.

- Faith in a vanguard who possess the saving knowledge.

- Readiness to use coercion to realize the dream.

From medieval millenarian sects to twentieth-century totalitarian states, these traits form a single continuum of spiritual rebellion: the attempt to perfect existence by abolishing its limits.

3. The Open Soul and the Pathologies of Closure

Against the Gnostic impulse stands the open soul—the philosophical disposition that accepts the “metaxy,” or the in-between nature of human existence. We live neither wholly in transcendence nor wholly in immanence, but within the tension between them. The philosopher’s task is not to resolve that tension through fantasy or reduction but to dwell within it in faith and reason.

Political science, therefore, must be noetic—concerned with insight into the structure of reality—not merely empirical. A society’s symbols, institutions, and laws can be judged by how faithfully they articulate humanity’s participation in divine order. Disorder, Voegelin warned, begins not with bad policy but with pneumopathology—a sickness of the spirit that refuses reality’s truth. “The order of history,” he wrote, “emerges from the history of order in the soul.”

Empirical data can measure economic growth or electoral results, but it cannot measure spiritual health. That requires awareness of being itself.

4. Liberalism’s Vulnerability and the Way of Recovery

Voegelin saw liberal democracies as historically successful yet spiritually precarious. By reducing political order to procedural legitimacy and rights management, liberalism risks drifting into the nihilism it opposes. When public life forgets its transcendent foundation, freedom degenerates into relativism, and pluralism becomes mere fragmentation.

Still, Voegelin’s outlook was not despairing. His proposed remedy was anamnesis—the recollective recovery of forgotten truth. This is not nostalgia but awakening: the rediscovery that human beings are participants in an order they did not create and cannot abolish. The recovery of the classic (Platonic-Aristotelian) and Christian understanding of existence offers the only durable antidote to ideological apocalypse (Voegelin 1952, 165–190).

To “keep open the soul,” as Voegelin put it, is to resist every movement that promises paradise through force or theory. The alternative is the descent into spiritual closure—an ever-recurring temptation of modernity.

5. Contemporary Resonance

Voegelin’s analysis remains uncannily prescient. Today’s ideological battles—whether framed around identity, technology, or climate—often echo the same Gnostic pattern: discontent with the world as it is, belief that perfection lies just one policy or re-education campaign away, and impatience with reality’s resistance. The post-modern conviction that truth is socially constructed continues the old dream of remaking existence through will and language.

Voegelin’s warning cuts through our century as clearly as it did the last: when politics replaces truth with narrative and transcendence with activism, society repeats the ancient heresy in secular form. The cure, as ever, is humility before what is—the recognition that order is discovered, not invented.

References

Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Glenn. 2003. Transcendence and History: The Search for Ultimacy from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Sandoz, Ellis. 1981. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glossary of Key Terms

Anamnesis – Recollective recovery of forgotten truth about being.

Gnosticism – Revolt against the tension of existence through claims to saving knowledge that masters reality.

Immanentize the eschaton – To locate final meaning and salvation within history rather than beyond it.

Metaxy – The “in-between” condition of human existence, suspended between immanence and transcendence.

Noetic – Pertaining to intellectual or spiritual insight into reality’s order.

Pneumopathology – Spiritual sickness of the soul that closes itself to transcendent reality.

Representation – The symbolic and political articulation of a society’s participation in transcendent order.

Before we can decide what is right, we must first know what is true. Yet our culture increasingly reverses this order, making moral conviction the starting point of thought rather than its conclusion. Peter Boghossian, the philosopher best known for challenging ideological thinking in academia, once argued that epistemology must precede ethics. The claim sounds abstract, but it describes a very practical problem: when we stop asking how we know, we lose the capacity to judge what’s right.

Epistemology—the study of how we know what we know—deals with questions of evidence, justification, and truth. It asks: What counts as knowledge? How do we tell when a belief is warranted? What standards should guide our acceptance of a claim? Ethics, by contrast, deals with what we should do, what is good, and what is right. The two are inseparable, but they are not interchangeable. Ethics without epistemology is like navigation without a compass: passionate, determined, and directionless.

The Missing First Question

Socrates, history’s first great epistemologist, spent his life asking not “What is right?” but “How do you know?” In dialogues like Euthyphro, he exposes the instability of moral conviction built on unexamined belief. When his interlocutor claims to know what “piety” is because the gods approve of it, Socrates presses: Do the gods love the pious because it is pious, or is it pious because the gods love it? In that moment, ethics collapses into epistemology—the question of truth must be settled before morality can stand.

This ordering of inquiry—first truth, then virtue—was not mere pedantry. Socrates saw that unexamined moral certainty leads to cruelty, because it allows one to justify any act under the banner of righteousness. He was eventually executed by men convinced they were defending moral order. His death, paradoxically, vindicated his philosophy: without the discipline of knowing, moral zealotry becomes indistinguishable from moral error.

Why Epistemology Matters

Epistemology is not a luxury for philosophers; it is the foundation of all responsible action. It demands that we distinguish between evidence and wishful thinking, between understanding and propaganda. To have a sound epistemology is to have habits of mind—skepticism, curiosity, proportion, humility—that protect us from self-deception.

When those habits decay, moral reasoning falters. Consider the Salem witch trials. The judges sincerely believed they were protecting their community from evil, yet their evidence—dreams, hearsay, spectral visions—was epistemically bankrupt. Their moral horror was real; their epistemic standards were not. The result was ethical disaster.

We see similar failures today whenever moral conviction outruns verification. A viral video circulates online; a crowd declares guilt before facts emerge. Outrage replaces investigation. The moral fervor feels righteous because it’s anchored in empathy or justice—but its epistemic foundation is sand. Ethical action requires knowing what actually happened, not what we wish had happened.

When Knowing Guides Doing

When epistemology is sound, ethics becomes coherent, fair, and humane.

Take the principle “innocent until proven guilty.” It is not primarily a moral rule; it is an epistemic one. It asserts that belief in guilt must be justified by evidence before punishment can be ethically administered. That epistemic restraint is what makes justice possible.

The same holds true in science. Before germ theory, doctors believed disease arose from “bad air,” leading them to act ethically—by their lights—yet ineffectively. Once scientific evidence clarified the true cause of infection, moral duties became clearer: sterilize instruments, wash hands, protect patients. Knowledge refined morality. Sound epistemology made better ethics possible.

John Stuart Mill saw this dynamic as essential to liberty. In On Liberty, he wrote that “he who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.” Mill’s insight is epistemological but its consequences are ethical: humility in belief breeds tolerance in practice. A society that cultivates open inquiry and debate is not merely more intelligent—it is more moral. For Mill, the freedom to question was not just an intellectual right but a moral obligation to prevent the tyranny of false certainty.

The Modern Inversion: Ethics Before Epistemology

Boghossian’s warning is timely because modern culture tends to invert the proper order. Many moral debates now begin not with questions of truth but with declarations of allegiance—what side are you on? The epistemic virtues of skepticism, evidence, and debate are recast as moral vices: to question a prevailing narrative is “denialism,” to request evidence is “harmful,” to doubt is “bigotry.”

The result is a moral discourse unanchored from truth. People act with conviction but without comprehension, certain of their goodness yet blind to their errors. Boghossian’s point is not that ethics are unimportant but that they cannot stand alone. If we do not first establish how we know, then our “oughts” become detached from reality, and moral judgment degenerates into moral fashion.

Hannah Arendt, reflecting on the moral collapse of ordinary Germans under Nazism, described this as the banality of evil—evil committed not from monstrous intent but from thoughtlessness. For Arendt, the failure was epistemic before it was ethical: people stopped thinking critically about what was true, deferring instead to the slogans and appearances sanctioned by authority. Their moral passivity was the fruit of epistemic surrender.

This same danger confronts us whenever ideology replaces inquiry—when images and narratives dictate belief before evidence is examined. To act justly, we must first see clearly; to see clearly, we must learn how to know.

The Cave and the Shadows

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave captures the enduring tension between knowledge and morality. Prisoners, chained since birth, mistake the shadows on the wall for reality. When one escapes and sees the sunlit world, he realizes how deep the deception ran. But when he returns to free the others, they resist, preferring the comfort of illusion to the pain of enlightenment.

We are those prisoners whenever we take appearances for truth—when we confuse social consensus with knowledge or mistake moral passion for understanding. The shadows dance vividly before us in the glow of our screens, and we feel certain we are seeing the world as it is. But unless we discipline our minds—testing claims, questioning sources, distinguishing truth from spectacle—we remain captives.

The allegory endures because it teaches that the pursuit of truth is not an abstract exercise but a moral struggle. To turn toward the light is to accept the discomfort of doubt, the humility of error, and the labor of learning. That discipline is the beginning of both knowledge and virtue.

Truth as the First Kindness

Epistemology precedes ethics because truth precedes goodness. To act ethically without first grounding oneself in what is true is to risk doing harm in the name of good. Socrates taught us to ask how we know; Mill reminded us to hear the other side; Arendt warned us what happens when we stop thinking; and Boghossian calls us back to the first principle that makes all ethics possible: the honest pursuit of truth.

In an age that rewards outrage over understanding, defending epistemology may seem quaint. Yet it is precisely our only defense against the moral chaos of a world that feels right but knows nothing.

Before we can do good, we must first be willing to know.

Truth, as it turns out, is the first kindness we owe one another.

References

- Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

- Boghossian, P. (2013). A Manual for Creating Atheists. Durham, NC: Pitchstone Publishing.

- Boghossian, P. (2006). “Epistemic Rules.” The Journal of Philosophy, 103(12), 593–608.

- Mill, J. S. (1859). On Liberty. London: John W. Parker and Son.

- Plato. (c. 380 BCE). The Republic, Book VII (The Allegory of the Cave). Translated by Allan Bloom, Basic Books, 1968.

- Plato. (c. 399 BCE). Euthyphro. In The Dialogues of Plato, translated by G.M.A. Grube. Hackett, 1981.

- Salem Witch Trials documentary sources: Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. University of Virginia, 2020.

- Socratic method reference: Vlastos, G. (1991). Socratic Studies. Cambridge University Press.

Author’s Reflection:

This piece was drafted with the aid of AI tools, which accelerated research and organization. Still, every idea here has been examined, rewritten, and affirmed through my own reasoning. Since the essay itself argues that epistemology must precede ethics, it seemed right to disclose the epistemic means by which it was written.

Your opinions…