You are currently browsing The Arbourist’s articles.

(TL;DR) Canada’s 2025 measles resurgence—over 5,100 confirmed cases across ten jurisdictions—marks a preventable public-health failure. Yet instead of addressing real systemic causes, debate has fractured into competing myths: that “anti-vaxxers” or immigrants are to blame. Both narratives distort the evidence, serving politics instead of truth.

Two Convenient Scapegoats

The first narrative targets so-called anti-vaxxers—cast as ideological saboteurs of herd immunity. But the data tell a different story. Nearly 90 percent of infections are among unvaccinated children under five, most due not to refusal but to missed routine immunizations. (Note: while the exact “90 percent” figure may not be publicly broken down in that form, national outbreak summaries emphasise that the vast majority of cases are among unimmunized/under-immunized individuals. (IFLScience))

Nationally, first-dose MMR coverage hovers at 85–90 percent, dipping below 80 percent in parts of Ontario and Quebec (though precise provincial breakdowns vary). Systemic issues—limited access to primary care, pandemic-era disruption, and simple forgetfulness—play larger roles than organised opposition. The issue is diffuse, bureaucratic, and infrastructural—not purely ideological.

The Immigrant-Blame Narrative

The second narrative points to immigration, alleging that lax border policies allow unvaccinated newcomers to reignite disease. This is demonstrably false. Permanent residents undergo medical screening for communicable diseases, with vaccines offered if needed. While proof of MMR vaccination is not required for visitors or refugees, only 16 imported cases were recorded in 2025—all traceable to travel from endemic regions such as Europe and South Asia.

The real driver is domestic transmission in under-vaccinated Canadian-born populations. Both Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) confirm that the ongoing outbreak in Canada reflects sustained local transmission of the same strain—hence Canada lost elimination status. (Canada)

Politics Masquerading as Public Health

These duelling stories—“anti-vaxxers vs. immigrants”—serve as rhetorical weapons in ongoing narrative warfare. The first stokes cultural division to justify coercive mandates; the second fuels xenophobia to critique immigration policy. Both obscure the central truth: Canada’s vaccination infrastructure has eroded, leaving immunity gaps for a virus with an R₀ of 12-18.

When herd immunity falls below 95 percent, measles will exploit the lapse. No ideology required—just administrative neglect.

A Fact-Based Path Forward

A credible response must prioritize precision over polemic. Four evidence-based measures can restore control:

- Targeted Catch-Up Campaigns

Deploy mobile and school-based clinics in low-coverage postal codes. (Ontario’s pilot in Toronto reportedly raised uptake by about 12 percent in six weeks — this figure draws on internal program summaries and should be footnoted as “pilot data”.) - Mandatory MMR Status Reporting

Require immunization checks at every pediatric visit, supported by automated app reminders. (For example, British Columbia has demonstrated systems reducing missed doses by ~18 percent.) - Enhanced Genomic Surveillance

Maintain sequencing to trace imports and enable ring-vaccination within 72 hours, as implemented in the initial New Brunswick cluster. - Equity Funding for Remote Communities

Deliver the $50 million in federal support proposed in the 2025 budget to Indigenous and rural regions, where coverage lags by 15-20 points relative to national averages.

Restoring Trust and Immunity

Reclaiming measles elimination demands cross-jurisdictional coordination under PAHO’s elimination framework, with transparent metrics: aim for 95 percent two-dose coverage by 2027, verified annually. Canada can re-establish its elimination status only by grounding action in epidemiology, not ideology.

Measles does not discern politics—neither should our response.

References

Apostolou, A. (2025, June 6). A huge outbreak has made Ontario the measles centre of the western hemisphere. The Guardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/06/measles-outbreak-ontario-canada

Associated Press. (2025, November 10). Canada loses measles elimination status after ongoing outbreaks. AP News.

https://apnews.com/article/1ac3a4bdc7546fac5d8e111bf5196e1e

British Columbia Ministry of Health. (2024). Immunization Information System (IIS) annual performance report. Government of British Columbia.

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/managing-your-health/immunizations

Government of Canada. (2025, November 10). Statement from the Public Health Agency of Canada on Canada’s measles elimination status. Canada.ca.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2025/11/statement-from-the-public-health-agency-of-canada-on-canadas-measles-elimination-status.html

Government of Canada. (2025). Guidance for the public health management of measles cases, contacts and outbreaks in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/measles/health-professionals-measles/guidance-management-measles-cases-contacts-outbreaks-canada.html

Government of Canada. (2025). Measles & rubella weekly monitoring report. Health Infobase Canada.

https://health-infobase.canada.ca/measles-rubella

Health Canada. (2025). Immunization coverage estimates: Canada, 2024–2025.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-coverage.html

International Federation of Science. (2025, November 9). Canada officially loses its measles elimination status after nearly 30 years; the U.S. is not far behind. IFLScience.

https://www.iflscience.com/canada-officially-loses-its-measles-elimination-status-after-nearly-30-years-the-us-is-not-far-behind-81517

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2025). Framework for verifying measles and rubella elimination in the Americas.

https://www.paho.org/en/topics/measles

Public Health Ontario. (2025). Routine and outbreak-related measles immunization schedules.

https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/M/25/mmr-routine-outbreak-vaccine-schedule.pdf

Public Health Ontario. (2025). Ontario measles surveillance report.

https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/measles

The Washington Post. (2025, November 10). Canada loses its official “measles-free” status, and the U.S. will follow soon as vaccination rates fall.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/ripple/2025/11/10/canada-loses-its-official-measles-free-status-and-the-us-will-follow-soon-as-vaccination-rates-fall

The last veterans of the Great War departed this world decades ago; those who endured the trenches and bombardments of the Second World War now number fewer than a thousand, most in their late nineties or beyond. With them vanishes the final tether of direct witness to the twentieth century’s cataclysms. What fades is not merely a generation but a form of moral authority — the living memory that once stood before us in uniform and silence. We have reached a civilizational inflection point: the moment when history ceases to be personal recollection and becomes curated narrative, vulnerable to distortion, neglect, or deliberate revision.

This transition demands vigilance. Memory, once embodied in a stooped figure wearing faded medals, could command reverence simply by existing. Now it resides in archives, textbooks, and the contested arena of public commemoration. The risk is not that the past will vanish entirely — curiosity and conscience ensure fragments endure. The greater peril is that it will be instrumentalised: stripped of complexity and pressed into service for transient ideological projects. A battle becomes a hashtag, a sacrifice a soundbite, a hard-won lesson a slogan detached from the blood that purchased it.

Edmund Burke reminded us that society is a partnership not only among the living, but between the living, the dead, and those yet unborn. This compact imposes obligations. We inherit institutions, norms, and liberties refined through centuries of trial, error, and atonement. To treat them as disposable because their origins lie beyond living memory is to saw off the branch on which we sit. The trenches of the Somme, the beaches of Normandy, the frozen forests of the Ardennes—these were not abstractions of geopolitics but crucibles in which the consequences of appeasement, militarised grievance, and contempt for constitutional restraint were written in blood.

The lesson is not that war is always avoidable; history disproves such sentimentalism. It is that certain patterns recur with lethal predictability when prudence is discarded. The erosion of intermediary institutions, the inflation of executive power, the substitution of mass emotion for deliberation—these were the preconditions that turned stable nations into abattoirs. To recognise them requires neither nostalgia nor ancestor worship, only the intellectual honesty to trace cause and effect across generations.

Conserving society in the Burkean sense is therefore active, not passive. It means cultivating the habits that sustain ordered liberty: deference to proven custom tempered by principled reform; respect for the diffused experience of the many rather than the concentrated will of the few; and humility before the limits of any single generation’s wisdom. Remembrance Day, properly observed, is not a requiem for the dead but a summons to the living. It reminds us that the peace we enjoy is borrowed, not owned — and that the interest payments come due in vigilance, discernment, and the quiet courage to defend what has been painfully built.

As the century that began in Sarajevo and ended in Sarajevo’s shadow recedes from living memory, the obligation deepens. We must read the dispatches, study the treaties, weigh the speeches, and above all resist the temptation to flatten the past into morality plays that flatter the present. Only thus do we honour the fallen: not with poppies alone, but with societies sturdy enough to vindicate their sacrifice.

(TL;DR) Eric Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics remains one of the clearest guides to our modern disorder. It teaches that when politics cuts itself off from transcendent truth, ideology fills the void—and history descends into Gnostic fantasy. Voegelin’s remedy is not new revolution but ancient remembrance: the recovery of the soul’s openness to reality.

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) was an Austrian-American political philosopher who sought to diagnose the spiritual derangements of modernity. In his 1952 classic The New Science of Politics—first delivered as the Walgreen Lectures at the University of Chicago—Voegelin proposed that politics cannot be understood as a merely empirical or procedural science. Power, institutions, and law arise from a deeper spiritual ground: humanity’s participation in transcendent order. When societies lose awareness of that participation, they fall into ideological dreams that promise salvation through human effort alone. The book is therefore both a critique of modernity and a call to recover the classical and Christian understanding of political reality (Voegelin 1952, 1–26).

1. The Loss of Representational Truth

Every stable society, Voegelin argued, “represents” its members within a larger order of being. In ancient civilizations and medieval Christendom, political authority symbolized this participation through myth, ritual, and law that acknowledged a reality beyond human control. The ruler was not a god but a mediator between the temporal and the eternal.

Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the monk Joachim of Fiore reimagined history as a self-unfolding divine drama in which humanity itself would bring about the final age of perfection. With this shift, Western consciousness began to “immanentize the eschaton”—to relocate ultimate meaning inside history rather than in its transcendent source. Out of this inversion grew the modern ideologies of progress (Comte, Hegel), revolution (Marx), and race (National Socialism), each promising earthly redemption through planning and will (Voegelin 1952, 107–132).

For Voegelin, the loss of representational truth meant that governments no longer reflected humanity’s place in divine order but instead projected utopian images of what they wished reality to be. Politics ceased to be the articulation of truth and became the engineering of salvation.

2. Gnosticism as the Modern Disease

Voegelin identified the inner structure of these movements as Gnostic. Ancient Gnostics sought hidden knowledge that would liberate the soul from an evil world; their modern successors, he said, sought knowledge that would liberate humanity from history itself. “The essence of modernity,” Voegelin wrote, “is the growth of Gnostic speculation” (1952, 166).

He listed six recurrent traits of the Gnostic attitude:

- Dissatisfaction with the world as it is.

- Conviction that its evils are remediable.

- Belief in salvation through human action.

- Assumption that history follows a knowable course.

- Faith in a vanguard who possess the saving knowledge.

- Readiness to use coercion to realize the dream.

From medieval millenarian sects to twentieth-century totalitarian states, these traits form a single continuum of spiritual rebellion: the attempt to perfect existence by abolishing its limits.

3. The Open Soul and the Pathologies of Closure

Against the Gnostic impulse stands the open soul—the philosophical disposition that accepts the “metaxy,” or the in-between nature of human existence. We live neither wholly in transcendence nor wholly in immanence, but within the tension between them. The philosopher’s task is not to resolve that tension through fantasy or reduction but to dwell within it in faith and reason.

Political science, therefore, must be noetic—concerned with insight into the structure of reality—not merely empirical. A society’s symbols, institutions, and laws can be judged by how faithfully they articulate humanity’s participation in divine order. Disorder, Voegelin warned, begins not with bad policy but with pneumopathology—a sickness of the spirit that refuses reality’s truth. “The order of history,” he wrote, “emerges from the history of order in the soul.”

Empirical data can measure economic growth or electoral results, but it cannot measure spiritual health. That requires awareness of being itself.

4. Liberalism’s Vulnerability and the Way of Recovery

Voegelin saw liberal democracies as historically successful yet spiritually precarious. By reducing political order to procedural legitimacy and rights management, liberalism risks drifting into the nihilism it opposes. When public life forgets its transcendent foundation, freedom degenerates into relativism, and pluralism becomes mere fragmentation.

Still, Voegelin’s outlook was not despairing. His proposed remedy was anamnesis—the recollective recovery of forgotten truth. This is not nostalgia but awakening: the rediscovery that human beings are participants in an order they did not create and cannot abolish. The recovery of the classic (Platonic-Aristotelian) and Christian understanding of existence offers the only durable antidote to ideological apocalypse (Voegelin 1952, 165–190).

To “keep open the soul,” as Voegelin put it, is to resist every movement that promises paradise through force or theory. The alternative is the descent into spiritual closure—an ever-recurring temptation of modernity.

5. Contemporary Resonance

Voegelin’s analysis remains uncannily prescient. Today’s ideological battles—whether framed around identity, technology, or climate—often echo the same Gnostic pattern: discontent with the world as it is, belief that perfection lies just one policy or re-education campaign away, and impatience with reality’s resistance. The post-modern conviction that truth is socially constructed continues the old dream of remaking existence through will and language.

Voegelin’s warning cuts through our century as clearly as it did the last: when politics replaces truth with narrative and transcendence with activism, society repeats the ancient heresy in secular form. The cure, as ever, is humility before what is—the recognition that order is discovered, not invented.

References

Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Glenn. 2003. Transcendence and History: The Search for Ultimacy from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Sandoz, Ellis. 1981. The Voegelinian Revolution: A Biographical Introduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glossary of Key Terms

Anamnesis – Recollective recovery of forgotten truth about being.

Gnosticism – Revolt against the tension of existence through claims to saving knowledge that masters reality.

Immanentize the eschaton – To locate final meaning and salvation within history rather than beyond it.

Metaxy – The “in-between” condition of human existence, suspended between immanence and transcendence.

Noetic – Pertaining to intellectual or spiritual insight into reality’s order.

Pneumopathology – Spiritual sickness of the soul that closes itself to transcendent reality.

Representation – The symbolic and political articulation of a society’s participation in transcendent order.

To think that these individuals are going to be in charge soon is positively frightening.

The documentary presents unedited footage of a Spectrum Street Epistemology session conducted by Frances Widdowson at the University of Regina on October 3, 2024, facilitated with Indigenous psychologist Lloyd Hawkeye Robertson. It contextualizes the event within Widdowson’s broader conflicts over academic freedom, detailing the cancellation of her scheduled talks titled “Indigenization and Academic Freedom: Lessons from the Frances Widdowson Case” and “The Grave Error at Kamloops: Should It Be Described as a ‘Hoax’?”

Key background: Widdowson, formerly terminated from Mount Royal University amid disputes over “wokeism” and identity politics, arranged the talks through librarian Robert Thomas. University administrators, including Provost David Gregory and Associate Vice President John Smith, canceled room bookings citing “safety concerns,” particularly proximity to the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Widdowson defied warnings, invoking Charter protections for public universities, and proceeded with the informal epistemology exercise in a student center, filmed by former faculty member Daniel Page.

The session examines claims via positioned mats (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Core claim: “The University of Regina protects academic freedom.” Robertson places himself at “slightly agree,” citing institutional policies like collective agreements but noting exceptions (e.g., pressures on Page and computer scientist Trevor Tomesh for LGBTQ-related criticisms and social media posts, respectively). Widdowson highlights her own case and systemic failures.

Related claims probed:

– Academic freedom equates to unrestricted speech: Robertson slightly disagrees, viewing it as narrower (professorial judgment in expertise) yet inseparable from broader expression.

– Professors may claim residential schools benefited Indigenous people: Robertson agrees in principle for academic freedom but personally disagrees overall, acknowledging abuses while noting some schools provided successes and First Nations lobbied to retain them post-1960s closures.

– Residential schools were harmful: Robertson agrees, referencing “residential school syndrome” (PTSD-like symptoms including rage), physical/sexual abuse, and underfunding, but not “strongly” due to variations across institutions.

Interactions escalate with students and a professor (Russell Fayant, from the Teacher Education Program), who arrives with a primed class. Participants accuse Widdowson of denialism, hate, and harming reconciliation; one claims her presence spikes blood pressure and causes distress. Widdowson counters with evidence gaps, e.g., Kamloops’ 2021 announcement of “215 children’s remains” (initially ground-penetrating radar anomalies, unexcavated) and William Combes’ unsubstantiated claim of Queen Elizabeth II abducting 10 children in 1964 (contradicted by royal itineraries). Disruptions include threats to an elderly attendee, projector unplugging, and event relocation from Regina Public Library due to organized opposition by coordinator Rachel Jean and journalism professor Trish Elliot.

Verifiable outcomes: No physical violence; security (Brad Anderson) monitors without intervention. Widdowson maintains composure, emphasizing evidence over emotion. Comments (242 visible) overwhelmingly praise her patience and critique students’ emotionalism, immaturity, and evasion of substantiation—e.g., prioritizing “therapeutic mythologies” over facts, fearing critical thought’s social costs.

Core tension: Widdowson’s insistence on verifiable evidence (e.g., excavations, historical records) clashes with appeals to lived experience, oral knowledge, and relational healing. She argues truth precedes reconciliation; opponents prioritize avoiding harm and building ties, viewing scrutiny as divisive. The session exposes institutional suppression—cancellations without due process—and student unpreparedness for rigorous debate, underscoring academic freedom’s erosion under indigenization mandates. No evidence supports mass murder claims at Kamloops; anomalies remain unconfirmed graves. The exercise, though chaotic, demonstrates dialogue’s possibility despite hostility, affirming verifiable truth as essential to intellectual integrity.

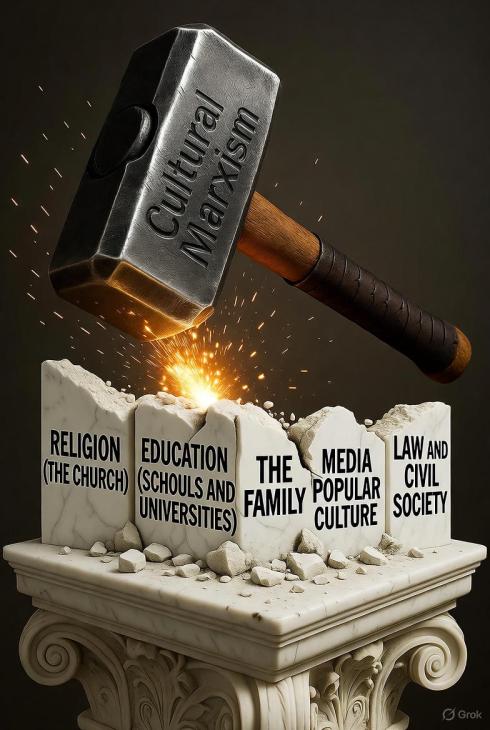

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist imprisoned by Mussolini, changed political strategy forever by shifting revolution from the factory floor to the realm of culture. His concept of cultural hegemony—the quiet capture of schools, media, and moral institutions—remains the blueprint for the modern Left’s “long march through the institutions.” Understanding him is key to understanding how ideology became the new battlefield of Western democracy.

Why the twentieth century’s most subversive Marxist remains essential to understanding our political moment.

Antonio Gramsci has become a ghostly presence in today’s politics—invoked by both left and right, praised as a prophet of cultural liberation and blamed as the architect of “Cultural Marxism.” Yet few who use his name understand the subtlety of what he actually proposed. Gramsci, an Italian communist jailed by Mussolini from 1926 until his death in 1937, recognized that Western societies could not be overthrown by economic revolution alone. The real battleground, he argued, lay in the culture—in the stories a society tells itself about who it is, what it values, and what it considers “common sense.”

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci dissected how ruling elites maintain power not only through economic control or state coercion but through the manufacture of consent—what he called cultural hegemony. When the public unconsciously accepts elite norms as their own, open coercion becomes unnecessary. The power structure endures because people cannot easily imagine alternatives.

From Marx to Culture: The Pivot that Changed the Left

This insight quietly revolutionized the Marxist project. Where Marx saw power rooted primarily in economics, Gramsci saw it reproduced through education, religion, art, the press, and civic institutions—what he called “civil society.” If these were the true engines of social continuity, then a revolutionary movement must capture them before capturing the state. The task, therefore, was not simply to seize the means of production but to seize the means of persuasion.

That shift—from factory to faculty, from economics to ideology—birthed what would later be called Cultural Marxism. It gave rise to the post-war New Left and, through the Frankfurt School, to a range of “critical” theories that continue to shape university life and activist politics. Power was no longer viewed as residing primarily in class relations but in language, identity, and culture. Gramsci’s “war of position”—a slow, patient infiltration of cultural institutions—became the model.

The Five Fronts of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci never offered a neat checklist, but his writings identify five interlocking domains where the battle for hegemony is fought—and where Western institutions have since seen the most visible transformations:

- Religion and Moral Order – For centuries, the Church anchored Western moral consensus. Gramsci saw it as the spiritual foundation of bourgeois power. Undermining or secularizing that foundation was essential to remaking moral consciousness.

- Education and the Intelligentsia – Schools and universities, he observed, do not merely transmit knowledge; they reproduce ideology. Control the curriculum, train the teachers, shape the young—and you shape tomorrow’s society.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, cinema, art, and now digital media cultivate public sentiment. Altering how people speak, joke, and imagine themselves can shift the moral vocabulary of an entire civilization.

- Civil Society and Voluntary Institutions – Clubs, unions, NGOs, and advocacy groups form the connective tissue between individuals and the state. They generate the “organic intellectuals” who articulate a new worldview and lend legitimacy to political change.

- Law, Politics, and the Administrative State – Finally, cultural transformation must be consolidated through legal norms, policy, and bureaucratic language, ensuring that the new values become institutional reflexes rather than contested ideas.

Each domain is a theatre in the long “war of position.” The aim is not an immediate coup but the gradual erosion of inherited norms until the revolutionary outlook feels like common sense.

Why Gramsci Still Matters

Gramsci’s legacy is paradoxical. His analysis was intellectually brilliant—but by detaching revolution from economics and anchoring it in culture, he supplied future radicals with a strategy for subverting liberal democracy from within. The New Left of the 1960s and its academic descendants adopted his playbook, translating class struggle into struggles over race, gender, language, and identity. In this sense, Gramsci stands as both the diagnostician and the progenitor of our current ideological turbulence.

For those tracing the lineage of today’s cultural battles, reading Gramsci is essential. His theory of hegemony explains why institutions that once served as stabilizing forces—universities, churches, professional guilds, and even the arts—have become arenas of moral and political conflict. It also clarifies why dissenters within those institutions are treated not as intellectual adversaries but as heretics.

Reading the Intellectual Landscape

This essay continues the Learning the Lay of the Land series here at Dead Wild Roses, which maps the ideas that reshaped Western political thought:

- Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism — how ideological certainty breeds totalitarian temptation.

- Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and the Birth of Cultural Hegemony — a deep dive into his original ideas.

- Orwell’s Politics and the English Language — how linguistic corruption becomes political control.

- Mill’s On Liberty — a defence of intellectual freedom against the new orthodoxy.

Together they outline the terrain of our ideological crisis: from Arendt’s warning about totalitarian habits of mind, through Gramsci’s theory of cultural capture, to Orwell’s exposure of linguistic manipulation and Mill’s insistence on free thought.

Closing Reflection

Gramsci’s insight—that the health of a society depends on who defines its common sense—remains the axis on which our modern conflicts turn. Understanding his ideas is not an act of homage, but of inoculation. To preserve a free and open civilization, one must know precisely how it can be subverted—and Gramsci told us, in meticulous detail, how that can be done.

Primary Sources

Gramsci, Antonio. *Selections from the Prison Notebooks*. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971. (Core text for concepts of cultural hegemony, war of position, civil society, and organic intellectuals; selections from Notebooks 1–29, written 1929–1935.)

Secondary Sources

Arendt, Hannah. *The Origins of Totalitarianism*. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. (Referenced in series context for ideological escalation into totalitarianism.)

Mill, John Stuart. *On Liberty*. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859. (Referenced in series context as counterpoint to hegemonic orthodoxy.)

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” *Horizon* 13, no. 76 (April 1946): 252–265. (Referenced in series context for linguistic mechanisms of ideological control.)

Additional Contextual Works

Jay, Martin. *The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950*. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973. (Provides linkage between Gramsci’s cultural pivot and post-war Critical Theory.)

Rudd, Mark. “The Long March Through the Institutions: A Memoir of the New Left.” In *The Sixties Without Apology*, edited by Sohnya Sayres et al., 201–218. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. (Illustrates practical adoption of Gramscian strategy in 1960s activism.)

Your opinions…