You are currently browsing The Arbourist’s articles.

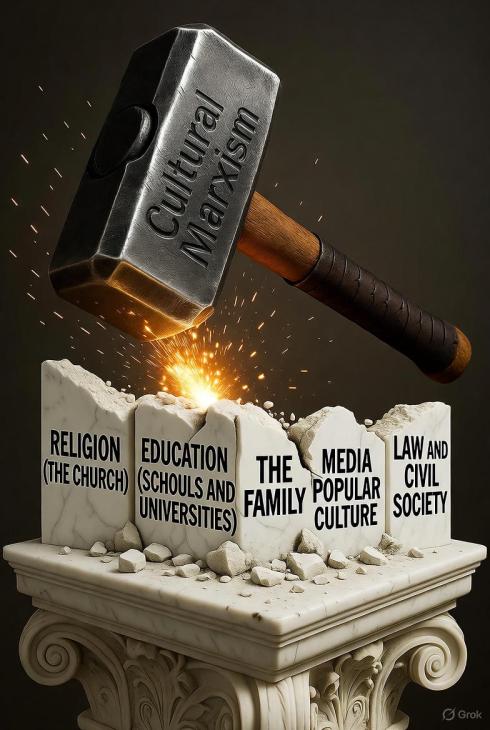

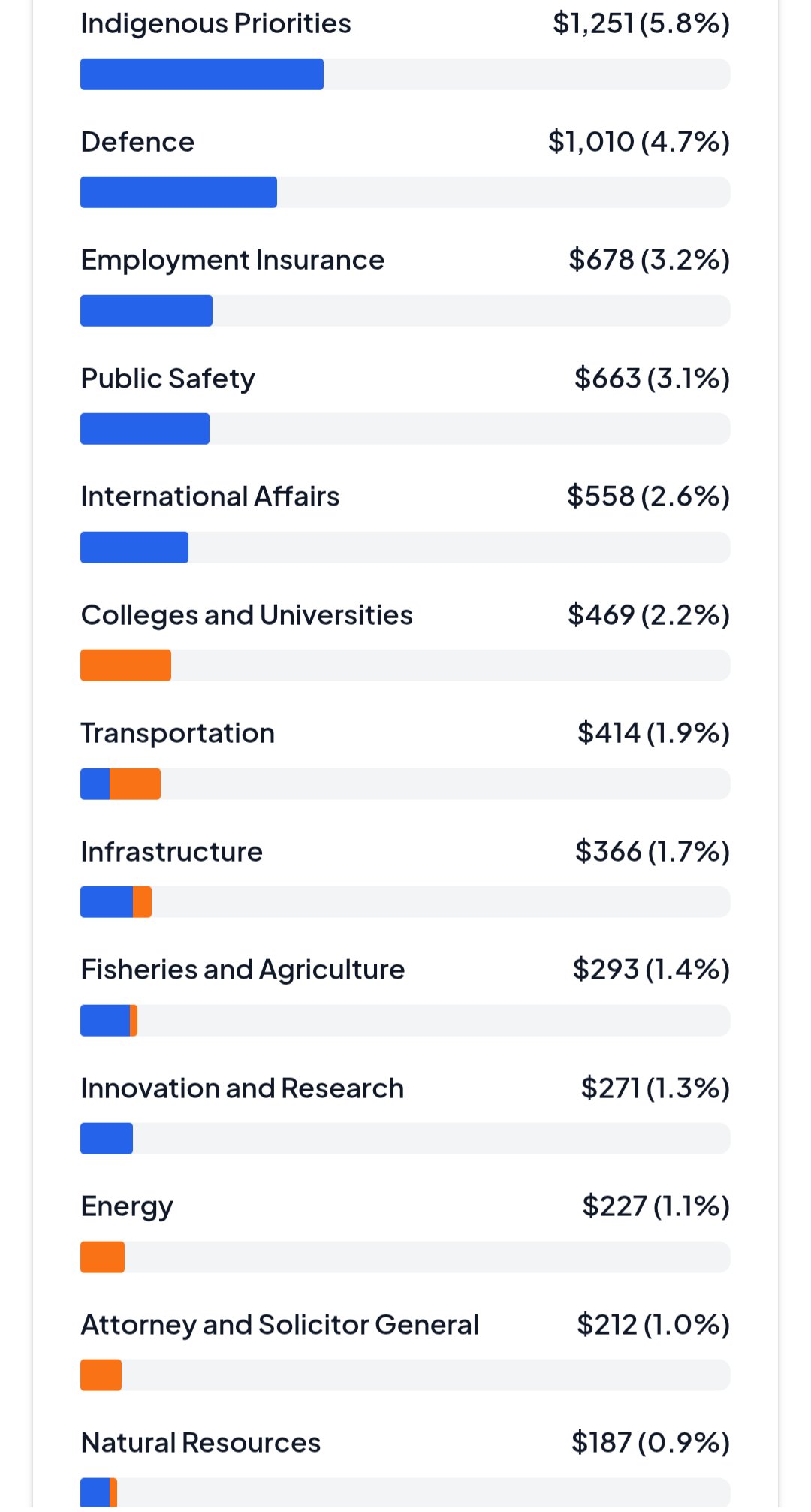

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist imprisoned by Mussolini, changed political strategy forever by shifting revolution from the factory floor to the realm of culture. His concept of cultural hegemony—the quiet capture of schools, media, and moral institutions—remains the blueprint for the modern Left’s “long march through the institutions.” Understanding him is key to understanding how ideology became the new battlefield of Western democracy.

Why the twentieth century’s most subversive Marxist remains essential to understanding our political moment.

Antonio Gramsci has become a ghostly presence in today’s politics—invoked by both left and right, praised as a prophet of cultural liberation and blamed as the architect of “Cultural Marxism.” Yet few who use his name understand the subtlety of what he actually proposed. Gramsci, an Italian communist jailed by Mussolini from 1926 until his death in 1937, recognized that Western societies could not be overthrown by economic revolution alone. The real battleground, he argued, lay in the culture—in the stories a society tells itself about who it is, what it values, and what it considers “common sense.”

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci dissected how ruling elites maintain power not only through economic control or state coercion but through the manufacture of consent—what he called cultural hegemony. When the public unconsciously accepts elite norms as their own, open coercion becomes unnecessary. The power structure endures because people cannot easily imagine alternatives.

From Marx to Culture: The Pivot that Changed the Left

This insight quietly revolutionized the Marxist project. Where Marx saw power rooted primarily in economics, Gramsci saw it reproduced through education, religion, art, the press, and civic institutions—what he called “civil society.” If these were the true engines of social continuity, then a revolutionary movement must capture them before capturing the state. The task, therefore, was not simply to seize the means of production but to seize the means of persuasion.

That shift—from factory to faculty, from economics to ideology—birthed what would later be called Cultural Marxism. It gave rise to the post-war New Left and, through the Frankfurt School, to a range of “critical” theories that continue to shape university life and activist politics. Power was no longer viewed as residing primarily in class relations but in language, identity, and culture. Gramsci’s “war of position”—a slow, patient infiltration of cultural institutions—became the model.

The Five Fronts of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci never offered a neat checklist, but his writings identify five interlocking domains where the battle for hegemony is fought—and where Western institutions have since seen the most visible transformations:

- Religion and Moral Order – For centuries, the Church anchored Western moral consensus. Gramsci saw it as the spiritual foundation of bourgeois power. Undermining or secularizing that foundation was essential to remaking moral consciousness.

- Education and the Intelligentsia – Schools and universities, he observed, do not merely transmit knowledge; they reproduce ideology. Control the curriculum, train the teachers, shape the young—and you shape tomorrow’s society.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, cinema, art, and now digital media cultivate public sentiment. Altering how people speak, joke, and imagine themselves can shift the moral vocabulary of an entire civilization.

- Civil Society and Voluntary Institutions – Clubs, unions, NGOs, and advocacy groups form the connective tissue between individuals and the state. They generate the “organic intellectuals” who articulate a new worldview and lend legitimacy to political change.

- Law, Politics, and the Administrative State – Finally, cultural transformation must be consolidated through legal norms, policy, and bureaucratic language, ensuring that the new values become institutional reflexes rather than contested ideas.

Each domain is a theatre in the long “war of position.” The aim is not an immediate coup but the gradual erosion of inherited norms until the revolutionary outlook feels like common sense.

Why Gramsci Still Matters

Gramsci’s legacy is paradoxical. His analysis was intellectually brilliant—but by detaching revolution from economics and anchoring it in culture, he supplied future radicals with a strategy for subverting liberal democracy from within. The New Left of the 1960s and its academic descendants adopted his playbook, translating class struggle into struggles over race, gender, language, and identity. In this sense, Gramsci stands as both the diagnostician and the progenitor of our current ideological turbulence.

For those tracing the lineage of today’s cultural battles, reading Gramsci is essential. His theory of hegemony explains why institutions that once served as stabilizing forces—universities, churches, professional guilds, and even the arts—have become arenas of moral and political conflict. It also clarifies why dissenters within those institutions are treated not as intellectual adversaries but as heretics.

Reading the Intellectual Landscape

This essay continues the Learning the Lay of the Land series here at Dead Wild Roses, which maps the ideas that reshaped Western political thought:

- Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism — how ideological certainty breeds totalitarian temptation.

- Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and the Birth of Cultural Hegemony — a deep dive into his original ideas.

- Orwell’s Politics and the English Language — how linguistic corruption becomes political control.

- Mill’s On Liberty — a defence of intellectual freedom against the new orthodoxy.

Together they outline the terrain of our ideological crisis: from Arendt’s warning about totalitarian habits of mind, through Gramsci’s theory of cultural capture, to Orwell’s exposure of linguistic manipulation and Mill’s insistence on free thought.

Closing Reflection

Gramsci’s insight—that the health of a society depends on who defines its common sense—remains the axis on which our modern conflicts turn. Understanding his ideas is not an act of homage, but of inoculation. To preserve a free and open civilization, one must know precisely how it can be subverted—and Gramsci told us, in meticulous detail, how that can be done.

Primary Sources

Gramsci, Antonio. *Selections from the Prison Notebooks*. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971. (Core text for concepts of cultural hegemony, war of position, civil society, and organic intellectuals; selections from Notebooks 1–29, written 1929–1935.)

Secondary Sources

Arendt, Hannah. *The Origins of Totalitarianism*. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. (Referenced in series context for ideological escalation into totalitarianism.)

Mill, John Stuart. *On Liberty*. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859. (Referenced in series context as counterpoint to hegemonic orthodoxy.)

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” *Horizon* 13, no. 76 (April 1946): 252–265. (Referenced in series context for linguistic mechanisms of ideological control.)

Additional Contextual Works

Jay, Martin. *The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950*. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973. (Provides linkage between Gramsci’s cultural pivot and post-war Critical Theory.)

Rudd, Mark. “The Long March Through the Institutions: A Memoir of the New Left.” In *The Sixties Without Apology*, edited by Sohnya Sayres et al., 201–218. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. (Illustrates practical adoption of Gramscian strategy in 1960s activism.)

Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) was an Italian Marxist philosopher and revolutionary who reimagined the battlefield of socialism. Where Marx envisioned revolution through economic crisis and class struggle, Gramsci located the real battleground in culture—in the stories, moral codes, and institutions that shape how people perceive reality. His insight reshaped leftist strategy throughout the 20th century and remains the foundation of what has come to be known, often critically, as Cultural Marxism.

Gramsci’s imprisonment by Mussolini between 1926 and 1937 produced the Prison Notebooks, a collection of reflections on history, education, religion, and power that would change Marxism forever. Rather than calling for immediate insurrection, Gramsci argued that Western societies were held together not merely by force, but by consent—the consent of people whose minds had been molded by dominant cultural institutions. To overthrow capitalism, the revolution would first have to capture culture.

The Concept of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci coined the term “cultural hegemony” to describe the way ruling classes maintain control by shaping what society considers “common sense.” Schools, churches, media, literature, and even family life all help reproduce the values that support the existing order. To Gramsci, the working class could never achieve political power until it produced a counter-hegemony—a rival moral and intellectual framework capable of displacing the dominant bourgeois worldview.

This insight was transformative. It shifted Marxist focus from economic structures to cultural superstructures—from factories to universities, from political parties to publishing houses. The revolution would be waged not only with rifles and manifestos, but with textbooks, art, and language itself.

The Five Pillars of Western Hegemony

Gramsci identified several key arenas where cultural hegemony is maintained and where revolutionary transformation must occur. Though he never formally listed “five areas,” his writings consistently emphasize these interlocking domains as the loci of bourgeois cultural power:

- Religion (The Church) – The Church was, for Gramsci, the moral anchor of Western civilization. Its authority shaped notions of duty, sin, and redemption. For a new socialist order to take root, Marxists would need to displace religious authority with secular, materialist moral systems.

- Education (Schools and Universities) – Schools reproduce social hierarchies by transmitting the ideology of the ruling class. Gramsci saw education as the most potent tool for cultivating a new “collective will.” Intellectuals, teachers, and professors were to become “organic intellectuals” of the working class—agents of counter-hegemony.

- The Family – As the smallest unit of moral and cultural reproduction, the family passes on norms of obedience, gender roles, and private property. Gramsci argued that socialist transformation required reconfiguring family life to reflect collective rather than patriarchal or bourgeois values.

- Media and Popular Culture – Newspapers, radio, and entertainment function as instruments of social consent. Control over communication channels would allow the revolutionary movement to redefine reality itself—to make socialist ideas seem natural and just.

- Law and Civil Society – Beyond the coercive power of the state lies civil society: courts, voluntary associations, clubs, and unions. These mediate between individuals and the state, embedding ruling-class ideology in everyday life. The Left’s long march through these institutions, later theorized by figures like Rudi Dutschke, stems directly from Gramsci’s idea of building a counter-hegemonic presence within civil society.

From Class War to Culture War

Gramsci’s influence has proven far greater than his lifetime achievements would suggest. His Prison Notebooks became a cornerstone for postwar Marxist thinkers of the Frankfurt School—Herbert Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, and others—who expanded his ideas into critical theory. Together, they seeded what would evolve into the New Left, identity-based activism, and much of today’s academic “social justice” thought.

While critics argue that Gramsci’s ideas have fostered divisive cultural politics, even they concede his enduring genius: he saw that culture precedes politics. Whoever controls a society’s moral vocabulary ultimately controls its laws, institutions, and collective imagination.

Why Gramsci Matters Today

Understanding Gramsci is essential to understanding the modern cultural landscape. His legacy explains why ideological movements increasingly contest meanings—of gender, race, language, and history—rather than material production. The “long march through the institutions” that Gramsci inspired is visible across Western education, media, and bureaucracies.

Whether one views this as intellectual renewal or cultural subversion, Gramsci’s insight endures: power begins in the mind before it manifests in law.

References

- Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 1971.

- Buttigieg, Joseph A. Antonio Gramsci: Prison Notebooks, Vols. I–III. Columbia University Press, 1992–2007.

- Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. University of California Press, 2002.

- Dutschke, Rudi. “The Long March Through the Institutions.” (Speech, 1967).

- Jay, Martin. The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950. University of California Press, 1973.

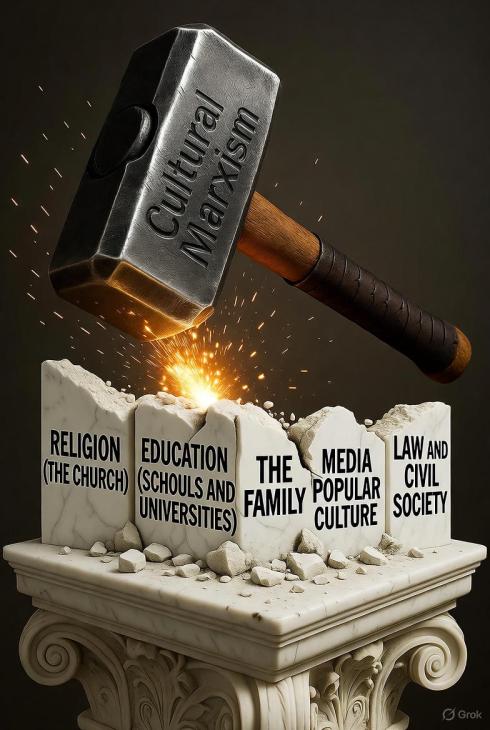

Canada’s federal budget tells a story that few seem willing to read critically. According to CanadaSpends.com, Ottawa allocates $1.251 billion—5.8 percent of the budget—to “Indigenous Priorities,” eclipsing even Defence ($1.010 billion, 4.7 percent). The arithmetic alone invites scrutiny. At what point does reconciliation become a fiscal reflex, untethered from measurable outcomes?

The Arithmetic of Imbalance

Consider a simple exercise in opportunity cost. Halving “Indigenous Priorities” to $625.5 million would free an equal amount—$625.5 million—for redeployment elsewhere. Redirecting that sum to Public Safety, currently $663 million (3.1 percent), would nearly double its capacity to $1.288 billion. The outcome: stronger policing resources, reinforced border security, and potentially measurable reductions in crime—objectives grounded in deterrence rather than symbolism.

This is not an argument against Indigenous advancement. It is an argument for proportionality and accountability. “Indigenous Priorities” now consume more than Employment Insurance ($678 million), International Affairs ($558 million), and Colleges and Universities ($469 million) combined. Defence, tasked with national sovereignty, trails by $241 million. When cultural or consultative programs eclipse citizen security and education, something in our fiscal compass is misaligned.

The Accountability Deficit

Proponents will cite historical redress, and that moral claim has force. But truth in budgeting requires evidence, not sentiment. Where are the audited outcomes showing that each billion spent yields measurable gains in Indigenous health, education, or economic independence?

The problem is not merely bureaucratic inertia—it is structural opacity, worsened by political choice. In December 2015, the newly elected Liberal government suspended enforcement of the First Nations Financial Transparency Act, which had required Indigenous governments to publish audited financial statements and leadership salaries. The minister at the time, Carolyn Bennett, directed her department to “cease all discretionary compliance measures” and reinstated funding to communities that refused disclosure.

In effect, Ottawa dismantled the only system ensuring public visibility into how billions of tax dollars are spent. Nearly a decade later, the Auditor General’s 2025 report found “unsatisfactory progress” on more than half of all Indigenous-services audit recommendations, despite an 84 percent increase in program spending since 2019. The data are undeniable: accountability has eroded even as expenditures have soared.

Fiscal Compassion, Not Fiscal Indulgence

Canada does not need less compassion; it needs measurable compassion—spending that demonstrably improves lives rather than perpetuates dependency. Halving the current Indigenous Priorities budget would not abolish support or reverse reconciliation. It would introduce accountability, allowing funds to be reallocated to public safety, infrastructure, or innovation—areas with immediate and empirically verifiable benefits.

Until Indigenous programs are evaluated with the same rigour applied to defence, education, or social insurance, billion-dollar gestures will remain ends in themselves—virtue without verification.

References

- CanadaSpends.com – Federal Tax Visualizer

- Government of Canada Statement on the First Nations Financial Transparency Act (2015)

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2025 Report – Programs for First Nations

- Canadian Affairs News – Poll: Canadians Want Transparency in First Nations Finances (2025)

- Standing Committee Appearance: Supplementary Estimates (2024)

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2023–24 Results Report

Alberta’s education system is at a breaking point. As more than 51,000 teachers strike across the province over oversized classrooms, the battle over class-size caps, staffing levels, and funding formulas has erupted into a full-blown crisis. With reports of classes swelling into the 30s and even 40s—and with the province no longer publishing detailed class-size data—the dispute between the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) and the Government of Alberta has become a referendum on whether quality learning can survive without clearer metrics, stricter rules, and targeted investments. This analysis examines the facts, details each side’s proposals, and steelmans both perspectives so readers can decide where the truth lies.

A Classroom Crisis or Budgetary Reality?

On October 6, 2025, teachers across Alberta walked out, declaring that the province’s classrooms have become “untenable.” The ATA’s strike action followed a decisive 89.5% rejection of the government’s offer—a signal of deep discontent.

(Source: Shootin’ the Breeze)

The core issues are class size, student complexity, and resource allocation. Teachers report classes of 30–40 students, rising numbers of high-needs children, and too few educational assistants or supports.

(Source: Learning Success Blog)

The government, meanwhile, stresses budget restraint, local flexibility, and warns that province-wide class caps would impose unsustainable costs.

What Do the Facts Reveal?

Data Transparency:

Until 2019, the province published annual class-size data for schools. In 2019, the current government ended that practice—making it difficult to establish accurate, province-wide numbers.

(Source: Braceworks)

Reported Trends:

An ATA survey found that 72% of Albertans believe class sizes are “too big,” while only 20% think they are “about right.”

(Source: ATA News)

Nearly 40% of teachers say their largest class has between 30 and 40 students; some exceed 40.

Funding and Growth:

In 2020, Alberta shifted to a three-year weighted moving average (WMA) for per-student funding. This was meant to stabilize budgets, but schools in fast-growing regions argue it made it harder to keep pace with enrollment increases.

(Source: Braceworks)

Together, these factors—rising enrollment, slower hiring, and more complex student needs—created the “classroom crisis” the ATA describes.

The ATA’s Position (Steelmanned)

- Binding Class-Size Caps:

The ATA calls for enforceable limits—especially smaller classes in early grades and high-needs classrooms. Oversized classes, they argue, reduce individualized feedback and classroom management capacity. - Staffing and Support for Complexity:

The ATA emphasizes that class composition matters as much as headcount. Classrooms with several students requiring individualized plans or behavioural supports demand additional staffing. - Funding to Hire 5,000+ Teachers:

To meet the province’s 2003 class-size recommendations, Alberta would need over 5,000 more teachers.

(Source: Swift News) - Quality of Learning:

The ATA contends this is not about wages—it’s about ensuring conditions where teachers can teach and students can learn.

In summary:

The ATA’s strongest case is that Alberta’s classrooms are objectively too large and complex for effective instruction, and only binding standards—backed by resources—can restore educational quality.

The Government’s Position (Steelmanned)

- Fiscal Responsibility:

The government argues that rigid caps would cost billions and force trade-offs with other priorities such as facilities and technology. - Local Flexibility:

Because school boards face different realities—urban crowding versus rural under-enrollment—the government says decisions should remain local, not imposed from Edmonton. - Targeted Investments, Not Blanket Caps:

The province has proposed hiring 3,000 teachers and 1,500 educational assistants over three years to focus on high-need areas, calling this a “strategic” alternative to universal caps.

(Source: CityNews Edmonton) - Continuity of Schooling:

The government invoked back-to-work legislation, arguing that prolonged strikes risk irreparable harm to students.

In summary:

The government’s steelmanned position is that it’s acting responsibly—preserving local flexibility, fiscal discipline, and stability while still targeting the worst pressure points.

What the Evidence Suggests

The educational research is nuanced:

- Smaller classes, especially in early grades, improve academic outcomes and behavioural management. (See: Project STAR, Krueger 2002)

- Benefits decline as grades rise or when teacher quality is not addressed simultaneously.

- Blanket reductions are expensive; targeted reductions often deliver higher returns per dollar.

Applied to Alberta:

The province may achieve the best results by targeting early-years and complex-needs classrooms, rather than imposing uniform caps across all grades. The evidence supports smaller classes where they matter most, not necessarily everywhere.

Where the Facts Should Lead Public Judgment

- Demand Transparency:

Reinstate province-wide class-size reporting so both government and ATA claims can be verified. - Target Early Grades and Complex Classes:

Evidence shows these investments yield the highest payoff. - Acknowledge Trade-offs:

Caps and hiring increases require billions in funding—citizens deserve clear accounting of costs and benefits. - Negotiate in Good Faith:

Both sides have legitimate claims: teachers on workload, government on fiscal prudence. A transparent mediation process focused on data—not ideology—would best serve students.

Final Thoughts

This strike is not just about teacher pay. It’s about the structure of public education itself—what class sizes are acceptable, how complexity is managed, and how Alberta balances fiscal discipline with classroom realities.

If your priority is student-centered learning and teacher retention, the ATA’s demand for enforceable caps has merit. If your focus is fiscal sustainability and flexibility, the government’s caution makes sense.

Either way, the solution must begin with facts: transparent class-size data, verifiable outcomes, and evidence-based reforms that put students first.

References

- Alberta Teachers’ Association – Class size issues top of mind for Albertans

- Learning Success Blog – Alberta’s 51,000 Teachers Strike Over Classroom Crisis as Class Sizes Hit 40 Students

- Braceworks – Alberta stopped tracking class sizes. Then it changed its funding formula. Now, it’s a teachers’ strike issue.

- Shootin’ the Breeze – Alberta teachers vote 95% for strike over wages and class sizes

- CityNews Calgary – Overcrowding in spotlight ahead of possible Alberta teachers strike

- Swift News – ATA Wants More Than 5,000 New Teachers To Meet Class-Size Recommendations

I’ve summarized the article here.

In challenging the prevailing narrative of unmitigated harm in Canada’s residential schools, Michelle Stirling scrutinizes Phyllis Webstad’s story, the inspiration behind Orange Shirt Day. Webstad boarded at St. Joseph’s in 1973, a facility under federal oversight where she attended public school alongside local children, not a cloistered religious institution. Stirling points out the absence of Catholic nuns in daily operations by that time, with Indigenous staff predominant, and questions the portrayal of familial abandonment on the Dog Creek Reserve amid documented violence, suggesting her placement served as a safeguard rather than an act of cultural erasure.

Vivian Ketchum’s recollection of being removed at age five to the Presbyterian-run Cecilia Jeffrey school is similarly contextualized as a welfare intervention, particularly against the backdrop of tuberculosis ravaging her community, which left her with lung scars. Stirling dismantles media distortions, such as those in “The Secret Path,” which erroneously inject Catholic elements into a Presbyterian setting, while citing Robert MacBain’s compilation of affirmative student letters that refute widespread abuse claims and highlight the school’s role as a refuge from dire home conditions.

Stirling ultimately cautions against the pitfalls of relying on childhood memories in legal compensation processes, where leading questions can shape recollections, and contrasts dominant tales with positive accounts like Lena Paul’s depiction of the school as a haven from familial turmoil. By exposing fabrications in works like the “Sugarcane” documentary, the article advocates for a balanced historical lens that prioritizes verifiable facts over emotive victimhood, fostering genuine reconciliation free from manipulated animosity.

Your opinions…