You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Islam’ tag.

If you missed what I’m talking about please look at the post from this Sunday’s The DWR Sunday Religious Disservice – Why Classical Islam and Western Liberalism Face Deep Tensions.

1) “You’re Confusing Islam with Islamism. The Problem Is Politics, Not the Religion.”

Steelman: Islamism is a modern political project. The ugly stuff is authoritarianism in religious costume. Islam as faith is diverse and reformable. Reformers exist. So don’t blame the religion for the politics.

My answer: The distinction is real. It just doesn’t rescue the claim.

Modern Islamism didn’t invent the collision with liberalism. It accelerated it. The collision is older, because it sits inside a legal tradition that treats divine law as public law, not private devotion.

Start with the liberal baseline: your right to change your beliefs without state punishment. The ICCPR treats freedom of thought, conscience, and religion as including the freedom “to have or to adopt” a religion of one’s choice, and bars coercion that impairs that freedom.[1] Yet apostasy laws still exist as state law in a chunk of the world. Pew counted apostasy laws in 22 countries in 2019.[2] That’s not “Islamism only.” That’s a standing fact about legal systems and what they’re willing to criminalize.

Then there are the asymmetries that aren’t modern inventions at all. The Qur’an’s inheritance rule that the male share is “twice that of the female” is explicit.[3] So is the debt-contract witness standard that requires one man and two women in that context.[4] You can contextualize these. You can argue for limited scope. You can try to reinterpret. But you can’t pretend the hard edges arrived in the 20th century.

So yes: reform is possible. But the obstacle is not merely “bad regimes.” It’s the weight of inherited jurisprudence plus institutions that treat that inheritance as binding.

If you want a clean test, use this: Is conscience sovereign? Including the right to leave the faith without legal penalty. Where the answer is no, liberalism exists on permission, not principle.

2) “Western Civilization Has Its Own History of Religious Violence and Oppression.”

Steelman: Christianity did crusades, inquisitions, heresy executions, and legal oppression. Liberalism took centuries. So singling out Islam is selective and hypocritical. Islam may simply be earlier in the same process.

My answer: Fair comparison. Now use it properly.

The West didn’t become liberal because Christians became nicer. It became liberal because religious authority was structurally pushed out of sovereignty over law and conscience. That’s the real lesson.

If “Islam can modernize” is your claim, then define modernization. It means a public order in which equal citizenship is non-negotiable and the right to belief and exit is protected in law.[1] You don’t get there by vibes. You get there by institutions.

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution is a useful example precisely because it shows the tension in plain language. It says the state is “guardian of religion,” while also guaranteeing “freedom of conscience and belief.”[5] That’s the struggle in one paragraph: which sovereignty rules when the two conflict?

Morocco’s family-law reforms are another example of the same dynamic. Over time, reforms have expanded women’s rights in areas like guardianship and divorce.[6] But even current reform proposals acknowledge a hard limit: inheritance rules grounded in Islamic law remain, with workarounds proposed through gifts and wills rather than direct replacement.[7] Again, that’s not a moral condemnation. It’s the mechanism. Reform runs into inherited authority.

So yes: the Western analogy shows change is possible. It also shows change is not automatic. It is conflict, choices, and enforcement.

3) “You’re Ignoring Diversity in the Muslim World and Overgeneralizing.”

Steelman: Nearly two billion adherents across many cultures and legal systems. Outcomes vary widely. Some Muslim-majority societies are relatively pluralistic. Sweeping statements are unfair.

My answer: Diversity is real. It just doesn’t settle the core question.

Different outcomes prove the future isn’t predetermined. They don’t prove the underlying tension disappears. In practice, “moderation” usually correlates with one thing: how far the state limits religious jurisdiction over public law.

Indonesia is the standard example. Its founding philosophy, Pancasila, is explicitly framed as a unifying civic ideology with principles including belief in one God, deliberative democracy, and social justice.[8] That civic framing matters. It can restrain sectarian rule. But it doesn’t end the conflict.

Indonesia’s newer criminal code debates show how quickly “public morality” and “religious insult” can become tools against liberty. Reuters’ explainer on the code flagged concerns over provisions related to blasphemy and other speech constraints.[9] Human Rights Watch argued the updated code expanded blasphemy provisions and warned about harms to rights, including religious freedom.[10] Reuters has also reported concrete blasphemy prosecutions, including a comedian jailed for jokes about the name Muhammad.[11]

So yes: diversity exists. Outcomes differ. But the recurring fault line remains: whether the state treats conscience and equal citizenship as the top rule, or treats religious law as a superior jurisdiction that liberalism must negotiate with.

Closing

The best objections don’t erase the problem. They refine it.

The conflict is not “Muslims are bad.” That’s a cheap and stupid sentence. The conflict is structural: a comprehensive religious-legal tradition claiming public authority collides with a political order grounded in sovereignty of individual conscience.[1]

You don’t solve that conflict by saying “it’s just politics.” You don’t solve it by reciting Western sins as a deflection. You don’t solve it by pointing to diversity and declaring victory.

A liberal society survives by enforcing liberal public order: one civil law for all, equal rights as the baseline, and no religious veto over belief, speech, or exit.[1] If you refuse to name that clearly, you don’t get “coexistence.” You get drift. And drift always has a direction.

References (URLs)

[1] OHCHR — International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 18

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

[2] Pew Research Center — Four in ten countries… had blasphemy laws in 2019 (includes apostasy law count) (Jan 25, 2022)

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/25/four-in-ten-countries-and-territories-worldwide-had-blasphemy-laws-in-2019-2/

[3] Qur’an 4:11 (inheritance shares) — Quran.com

https://quran.com/en/an-nisa/11-14

[4] Qur’an 2:282 (witness standard in debt contracts) — Quran.com

https://quran.com/en/al-baqarah/282

[5] Tunisia 2014 Constitution, Article 6 — Constitute Project

https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014

[6] Carnegie Endowment — Morocco Family Law (Moudawana) Reform: Governance in the Kingdom (Jul 28, 2025)

https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/07/morocco-family-law-moudawana-reform-governance?lang=en

[7] Reuters — Morocco proposes family law reforms to improve women’s rights (Dec 24, 2024)

https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/morocco-proposes-family-law-reforms-improve-womens-rights-2024-12-24/

[8] Encyclopaedia Britannica — Pancasila

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pancasila

[9] Reuters — Explainer: Why is Indonesia’s new criminal code so controversial? (Dec 6, 2022)

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-is-indonesias-new-criminal-code-so-controversial-2022-12-06/

[10] Human Rights Watch — Indonesia: New Criminal Code Disastrous for Rights (Dec 8, 2022)

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/08/indonesia-new-criminal-code-disastrous-rights

[11] Reuters — Indonesian court jails comedian for joking about the name Muhammad (Jun 11, 2024)

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesian-court-jails-comedian-joking-about-name-muhammad-2024-06-11/

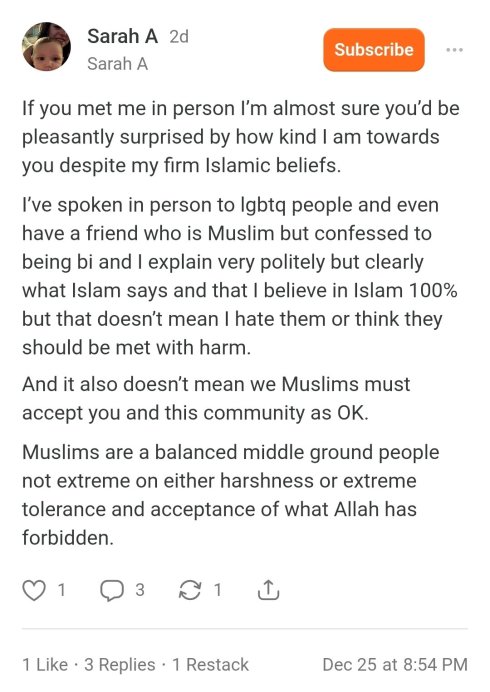

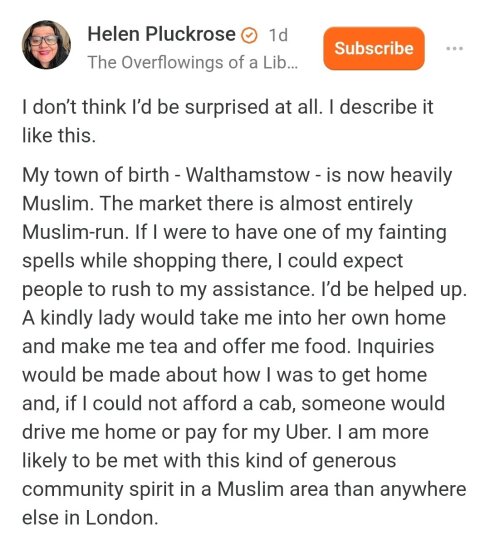

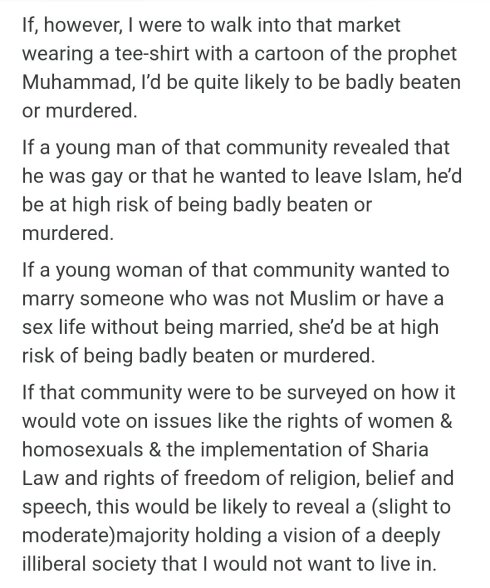

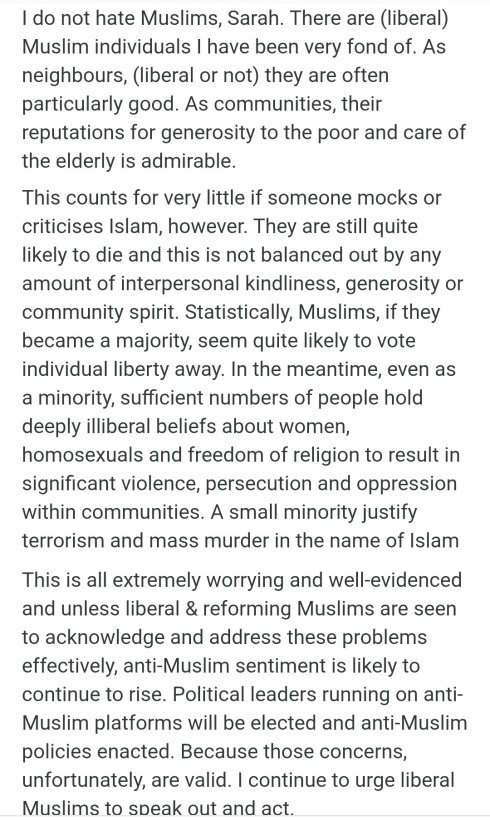

In a thoughtful exchange highlighted by James Lindsay, liberal writer Helen Pluckrose responds to a Muslim commenter who shares personal experiences of generosity within Muslim communities. While warmly acknowledging the kindness and charity she’s witnessed among individual Muslims, Pluckrose firmly points out the broader issue: widespread support in some Muslim populations for Sharia-based views that endorse severe punishments—including violence or death—for apostasy, homosexuality, adultery, and blasphemy. She argues that ignoring these illiberal attitudes, backed by polling data, risks fueling unnecessary backlash against Muslims while failing to address genuine incompatibilities with Western liberal values.

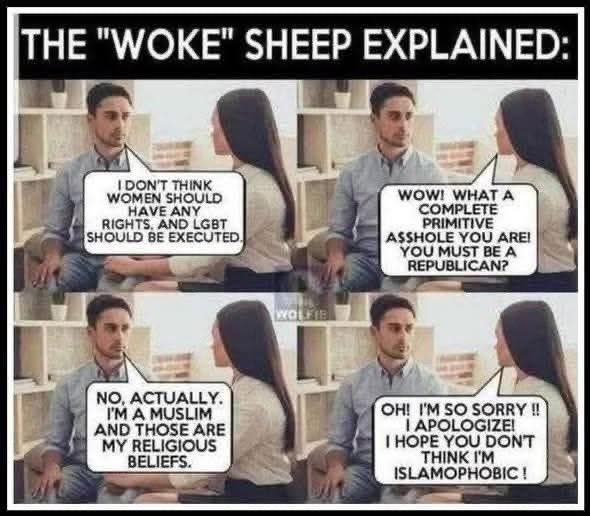

The meme is considered “fairly accurate” by critics of progressive politics because it captures a perceived double standard: while left-leaning activists routinely and aggressively condemn anti-LGBTQ+ views among Christians (e.g., evangelical opposition to same-sex marriage), they often hesitate to apply the same scrutiny to similar or stronger opposition within Muslim communities, instead framing such criticism as Islamophobic or culturally insensitive.

Surveys consistently show that Muslims, particularly in Europe and Muslim-majority countries, hold more conservative attitudes toward homosexuality than the general Western population—often viewing it as morally unacceptable due to religious interpretations—yet progressive voices tend to prioritize anti-Islamophobia efforts, sometimes downplaying or excusing these views under cultural relativism or minority protection. This selective outrage, observers argue, reflects a hierarchy of sensitivities where fear of racism accusations trumps consistent advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights, allowing illiberal positions to persist unchallenged in one context while being fiercely opposed in another.

When they are not running the show versus when they are running the show. Funny how that works.

Sunday DWR Religious Disservice: Radical Islamic Protests Clash with Canadian Values

The recent demonstrations at McGill University in April 2025, where anti-Israel protesters blocked lecture halls and disrupted classes, starkly illustrate the incompatibility of radical Islamic protests with Canadian values. As reported by B’nai Brith Canada, masked activists, some wearing keffiyehs, physically prevented students from accessing education, chanting slogans like “McGill, McGill you can’t hide, you’re complicit in genocide.” While the protests were framed as a call for divestment from companies linked to Israel, their tactics—intimidation and coercion—echo a broader pattern of radical Islamic activism that prioritizes ideological confrontation over dialogue. In Canada, a nation built on mutual respect and the rule of law, such actions undermine the principles of peaceful coexistence and individual rights that define our culture.

These protests not only disrupted academic life but also created an environment of fear, particularly for Jewish students, who felt targeted by what advocacy groups described as antisemitic behavior. The McGill demonstrations reflect a worldview that rejects Canada’s commitment to pluralism and freedom of expression, instead embracing a form of radicalism that seeks to impose its agenda through force. Historical insights, such as those from McGill’s Institute of Islamic Studies, highlight that radical Islam often merges religious ideology with political and social demands, as noted in a House of Commons report on the “clash of civilizations” thesis. This fusion can lead to a confrontational stance that clashes with Canadian culture, which values negotiation and inclusivity over exclusionary tactics that silence others.

These protests not only disrupted academic life but also created an environment of fear, particularly for Jewish students, who felt targeted by what advocacy groups described as antisemitic behavior. The McGill demonstrations reflect a worldview that rejects Canada’s commitment to pluralism and freedom of expression, instead embracing a form of radicalism that seeks to impose its agenda through force. Historical insights, such as those from McGill’s Institute of Islamic Studies, highlight that radical Islam often merges religious ideology with political and social demands, as noted in a House of Commons report on the “clash of civilizations” thesis. This fusion can lead to a confrontational stance that clashes with Canadian culture, which values negotiation and inclusivity over exclusionary tactics that silence others.

For the faithful, this serves as a reminder that true spirituality fosters harmony, not division. The McGill protests, with their roots in radical Islamic ideology, stand in stark contrast to Canada’s cultural ethos of tolerance and respect for all. As a nation, we must uphold our values by ensuring that protests, even those driven by deeply held beliefs, do not cross into intimidation or lawbreaking. The path to peace lies in dialogue and understanding, not in actions that alienate and divide—principles that should resonate with any community of faith seeking to live out its convictions in a diverse society.

Your opinions…