You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Ethics’ category.

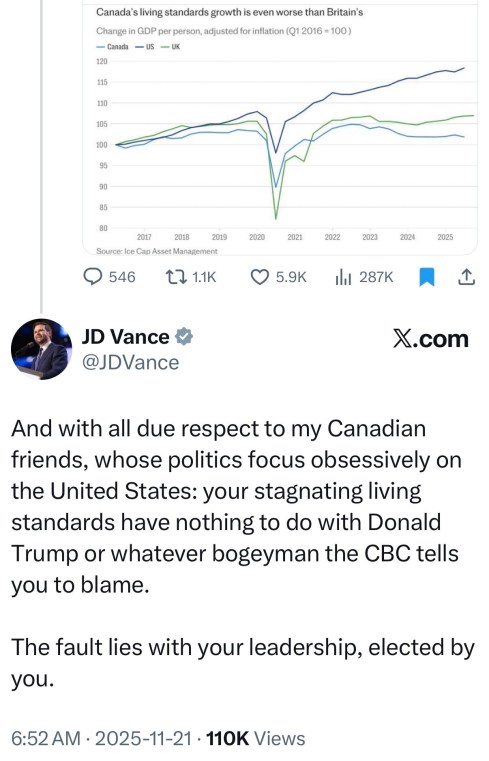

Canada finds itself at a crossroads. In recent years, per capita GDP growth has stalled, productivity remains sluggish, and housing, healthcare, and infrastructure face mounting pressure. These trends have prompted urgent debate about the causes of stagnation, ranging from global economic shifts and demographic aging to domestic policy decisions. Among commentators, JD Vance recently sparked attention with pointed critiques of Canada’s immigration policies and multicultural model, framing them as principal contributors to declining living standards. Beyond the immediate provocation, his intervention highlights a deeper question: how should Canadians assess responsibility for the state of their economy?

Immigration, Policy Choices, and Economic Outcomes

Canada’s foreign-born population now stands at approximately 23 percent, the highest in the G7, reflecting a sharp rise over the past decade. This increase was accelerated by post-pandemic labor shortages and policy decisions prioritizing high-volume admissions. While immigration is a crucial driver of population growth and labor supply, recent evidence indicates that integration has lagged, particularly for newcomers with credentials or skills mismatched to domestic demand. Unemployment rates among recent immigrants are approximately twice those of Canadian-born workers, and overall productivity growth has remained below historical trends.

These outcomes underscore a key point: while external factors including global commodity cycles, trade dynamics, and U.S. policy affect Canada’s economy, domestic decisions regarding immigration volume, infrastructure investment, and skills integration exert primary influence over living standards. The choice to expand immigration without simultaneously scaling capacity for integration, housing, and healthcare has consequences that voters ultimately authorize at the ballot box.

Stoic Lessons for Civic Responsibility

Confronted with these structural and policy realities, Canadians might feel tempted to externalize blame to markets, foreign governments, or pundits. Here, the Stoic philosophers offer timeless guidance. Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations: “You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” Epictetus similarly asserted: “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.” These principles demand that citizens distinguish between factors within their control and those beyond it, focusing energy on the former.

Stoicism is not a creed of passivity. It insists on rigorous self-examination and deliberate action. In Canada’s context, this means acknowledging the consequences of policy choices and recognizing that solutions—whether adjusting immigration strategy, improving integration programs, or investing in productivity-enhancing infrastructure—lie within domestic capacity.

Pathways to Renewal

Practical measures aligned with these principles include:

- Aligning immigration targets with absorptive capacity: Recent adjustments to temporary resident admissions, reducing projected numbers by approximately 43 percent, illustrate the potential for recalibration.

- Prioritizing skill-aligned integration: Investing in credential recognition, language training, and targeted labor placement can ensure that new arrivals contribute effectively to productivity.

- Strengthening domestic infrastructure and services: Housing, healthcare, and transportation require proportional investment to match demographic growth.

- Informed civic engagement: Voting with awareness of policy consequences is fundamental to maintaining democratic accountability and ensuring long-term economic stability.

By taking responsibility, Canadians act in accordance with Stoic precepts: focusing on what they can control rather than scapegoating external forces. The challenge is not merely economic—it is moral and civic. Prosperity depends as much on deliberate collective action as on external circumstance.

Conclusion

Canada’s stagnating living standards are the product of complex factors, yet domestic choices remain decisive. While commentary from external observers like JD Vance may provoke discomfort, the underlying lesson is clear: sovereignty entails responsibility, and agency begins at home. To confront stagnation, Canadians must embrace candid assessment of policy outcomes, deliberate reform, and disciplined civic engagement. In the words of Seneca: “We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” Facing the realities we have constructed—and acting to improve them—is the first step toward renewal.

References

- Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey, 2025. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data

- Government of Canada. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada: Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-parliament-immigration.html

- Marcus Aurelius. Meditations. Trans. Gregory Hays, 2002.

- Epictetus. Enchiridion. Trans. Elizabeth Carter, 1758.

- Seneca. Letters from a Stoic. Trans. Robin Campbell, 2004.

Glossary

- Per Capita GDP: The average economic output per person, often used as a measure of living standards.

- Productivity: Output per unit of input; a key driver of sustainable economic growth.

- Integration Programs: Policies and services designed to help immigrants participate effectively in the labor market and society.

- Absorptive Capacity: The ability of a system (economy, infrastructure, institutions) to accommodate growth without adverse effects.

- Stoicism: Philosophical framework emphasizing rational control over one’s mind and actions rather than external circumstances.

Before we can decide what is right, we must first know what is true. Yet our culture increasingly reverses this order, making moral conviction the starting point of thought rather than its conclusion. Peter Boghossian, the philosopher best known for challenging ideological thinking in academia, once argued that epistemology must precede ethics. The claim sounds abstract, but it describes a very practical problem: when we stop asking how we know, we lose the capacity to judge what’s right.

Epistemology—the study of how we know what we know—deals with questions of evidence, justification, and truth. It asks: What counts as knowledge? How do we tell when a belief is warranted? What standards should guide our acceptance of a claim? Ethics, by contrast, deals with what we should do, what is good, and what is right. The two are inseparable, but they are not interchangeable. Ethics without epistemology is like navigation without a compass: passionate, determined, and directionless.

The Missing First Question

Socrates, history’s first great epistemologist, spent his life asking not “What is right?” but “How do you know?” In dialogues like Euthyphro, he exposes the instability of moral conviction built on unexamined belief. When his interlocutor claims to know what “piety” is because the gods approve of it, Socrates presses: Do the gods love the pious because it is pious, or is it pious because the gods love it? In that moment, ethics collapses into epistemology—the question of truth must be settled before morality can stand.

This ordering of inquiry—first truth, then virtue—was not mere pedantry. Socrates saw that unexamined moral certainty leads to cruelty, because it allows one to justify any act under the banner of righteousness. He was eventually executed by men convinced they were defending moral order. His death, paradoxically, vindicated his philosophy: without the discipline of knowing, moral zealotry becomes indistinguishable from moral error.

Why Epistemology Matters

Epistemology is not a luxury for philosophers; it is the foundation of all responsible action. It demands that we distinguish between evidence and wishful thinking, between understanding and propaganda. To have a sound epistemology is to have habits of mind—skepticism, curiosity, proportion, humility—that protect us from self-deception.

When those habits decay, moral reasoning falters. Consider the Salem witch trials. The judges sincerely believed they were protecting their community from evil, yet their evidence—dreams, hearsay, spectral visions—was epistemically bankrupt. Their moral horror was real; their epistemic standards were not. The result was ethical disaster.

We see similar failures today whenever moral conviction outruns verification. A viral video circulates online; a crowd declares guilt before facts emerge. Outrage replaces investigation. The moral fervor feels righteous because it’s anchored in empathy or justice—but its epistemic foundation is sand. Ethical action requires knowing what actually happened, not what we wish had happened.

When Knowing Guides Doing

When epistemology is sound, ethics becomes coherent, fair, and humane.

Take the principle “innocent until proven guilty.” It is not primarily a moral rule; it is an epistemic one. It asserts that belief in guilt must be justified by evidence before punishment can be ethically administered. That epistemic restraint is what makes justice possible.

The same holds true in science. Before germ theory, doctors believed disease arose from “bad air,” leading them to act ethically—by their lights—yet ineffectively. Once scientific evidence clarified the true cause of infection, moral duties became clearer: sterilize instruments, wash hands, protect patients. Knowledge refined morality. Sound epistemology made better ethics possible.

John Stuart Mill saw this dynamic as essential to liberty. In On Liberty, he wrote that “he who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.” Mill’s insight is epistemological but its consequences are ethical: humility in belief breeds tolerance in practice. A society that cultivates open inquiry and debate is not merely more intelligent—it is more moral. For Mill, the freedom to question was not just an intellectual right but a moral obligation to prevent the tyranny of false certainty.

The Modern Inversion: Ethics Before Epistemology

Boghossian’s warning is timely because modern culture tends to invert the proper order. Many moral debates now begin not with questions of truth but with declarations of allegiance—what side are you on? The epistemic virtues of skepticism, evidence, and debate are recast as moral vices: to question a prevailing narrative is “denialism,” to request evidence is “harmful,” to doubt is “bigotry.”

The result is a moral discourse unanchored from truth. People act with conviction but without comprehension, certain of their goodness yet blind to their errors. Boghossian’s point is not that ethics are unimportant but that they cannot stand alone. If we do not first establish how we know, then our “oughts” become detached from reality, and moral judgment degenerates into moral fashion.

Hannah Arendt, reflecting on the moral collapse of ordinary Germans under Nazism, described this as the banality of evil—evil committed not from monstrous intent but from thoughtlessness. For Arendt, the failure was epistemic before it was ethical: people stopped thinking critically about what was true, deferring instead to the slogans and appearances sanctioned by authority. Their moral passivity was the fruit of epistemic surrender.

This same danger confronts us whenever ideology replaces inquiry—when images and narratives dictate belief before evidence is examined. To act justly, we must first see clearly; to see clearly, we must learn how to know.

The Cave and the Shadows

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave captures the enduring tension between knowledge and morality. Prisoners, chained since birth, mistake the shadows on the wall for reality. When one escapes and sees the sunlit world, he realizes how deep the deception ran. But when he returns to free the others, they resist, preferring the comfort of illusion to the pain of enlightenment.

We are those prisoners whenever we take appearances for truth—when we confuse social consensus with knowledge or mistake moral passion for understanding. The shadows dance vividly before us in the glow of our screens, and we feel certain we are seeing the world as it is. But unless we discipline our minds—testing claims, questioning sources, distinguishing truth from spectacle—we remain captives.

The allegory endures because it teaches that the pursuit of truth is not an abstract exercise but a moral struggle. To turn toward the light is to accept the discomfort of doubt, the humility of error, and the labor of learning. That discipline is the beginning of both knowledge and virtue.

Truth as the First Kindness

Epistemology precedes ethics because truth precedes goodness. To act ethically without first grounding oneself in what is true is to risk doing harm in the name of good. Socrates taught us to ask how we know; Mill reminded us to hear the other side; Arendt warned us what happens when we stop thinking; and Boghossian calls us back to the first principle that makes all ethics possible: the honest pursuit of truth.

In an age that rewards outrage over understanding, defending epistemology may seem quaint. Yet it is precisely our only defense against the moral chaos of a world that feels right but knows nothing.

Before we can do good, we must first be willing to know.

Truth, as it turns out, is the first kindness we owe one another.

References

- Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

- Boghossian, P. (2013). A Manual for Creating Atheists. Durham, NC: Pitchstone Publishing.

- Boghossian, P. (2006). “Epistemic Rules.” The Journal of Philosophy, 103(12), 593–608.

- Mill, J. S. (1859). On Liberty. London: John W. Parker and Son.

- Plato. (c. 380 BCE). The Republic, Book VII (The Allegory of the Cave). Translated by Allan Bloom, Basic Books, 1968.

- Plato. (c. 399 BCE). Euthyphro. In The Dialogues of Plato, translated by G.M.A. Grube. Hackett, 1981.

- Salem Witch Trials documentary sources: Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. University of Virginia, 2020.

- Socratic method reference: Vlastos, G. (1991). Socratic Studies. Cambridge University Press.

Author’s Reflection:

This piece was drafted with the aid of AI tools, which accelerated research and organization. Still, every idea here has been examined, rewritten, and affirmed through my own reasoning. Since the essay itself argues that epistemology must precede ethics, it seemed right to disclose the epistemic means by which it was written.

Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil remains one of the twentieth century’s most incisive dissections of moral failure. Published in 1963, the book emerged from Arendt’s firsthand reporting on the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, a mid-level Nazi bureaucrat whose role in orchestrating the deportation of millions of Jews to death camps defined the Holocaust’s logistical horror. Expectations ran high for a portrait of unalloyed monstrosity, yet Arendt delivered something far more unsettling: a portrait of profound ordinariness. Eichmann was no ideological zealot or sadistic fiend, but a careerist adrift in clichés and administrative jargon, driven by ambition and an unswerving commitment to hierarchy. From this unremarkable figure, Arendt forged her enduring concept of the banality of evil, a framework that exposes how systemic atrocities arise not from demonic intent but from the quiet abdication of critical thought.

The Trial That Shattered Expectations

Arendt arrived in Jerusalem as a correspondent for The New Yorker, tasked with chronicling the prosecution of Eichmann, the architect of the Nazis’ “Final Solution” in practice if not in origin. What she witnessed defied the trial’s dramatic staging. Eichmann, perched in his glass booth, projected not menace but mediocrity. He droned on in a flat, bureaucratic patois, insisting his actions stemmed from dutiful obedience rather than personal malice. “I never killed a Jew,” he protested, as if the euphemism absolved the machinery he oiled. This was no Iago or Macbeth, but a joiner par excellence: shallow, conformist, and utterly unable to grasp the human weight of his deeds. Arendt’s revulsion crystallized mid-trial, in her notebooks, where she first sketched the phrase that would redefine her legacy. The banality of evil was born not from Eichmann’s depravity, but from his incapacity for reflection—a thoughtlessness that rendered him complicit in genocide without the depth to comprehend it.

Unpacking the Banality: From Demonic to Mundane

At its core, the banality of evil upends the romanticized view of wickedness as inherently profound or radical. Evil, Arendt contended, often manifests as banal: the work of unimaginative souls who drift through conformity, failing to interrogate their roles in larger systems. Eichmann exemplified this through his linguistic sleight of hand. He evaded the raw truth of extermination, speaking instead of “transportations” and “processing,” terms that sanitized slaughter into spreadsheet entries. Hatred played little part; obedience, careerism, and social inertia sufficed. The terror lay in his normalcy. As Arendt observed, evil flourishes not among isolated monsters but in societies where individuals relinquish moral judgment to rules, authorities, or routines. This banality, she later clarified, arises from an active refusal to exercise judgment, transforming ordinary people into cogs of catastrophe.

Arendt wove this insight into her broader philosophical tapestry, where thinking emerges as the essential moral safeguard. In the Socratic tradition, genuine thought demands we question the rightness of our actions, bridging the gap between knowledge and ethics. Eichmann’s failure was not intellectual deficiency alone, but a willful suspension of this faculty—substituting slogans and protocols for scrutiny. She identified thoughtlessness as totalitarianism’s hallmark, a regime that trains citizens to obey without asking why, eroding the pluralistic dialogue vital to human freedom. Against this, Arendt posited “natality,” the human capacity for birth and renewal, as a counterforce: each new beginning compels us to initiate thought, disrupting entrenched banalities.

The Firestorm of Controversy

Arendt’s conclusions ignited immediate backlash. Critics, including Jewish intellectuals like Gershom Scholem, accused her of exonerating Eichmann and scapegoating victims by critiquing the Jewish councils’ coerced cooperation with Nazi demands. Her dispassionate tone struck many as callous, diluting the Holocaust’s singularity into a lesson in human frailty. Yet Arendt sought neither absolution nor minimization; her aim was diagnostic. Evil in bureaucratic modernity, she argued, stems from collective complicity, not just from fanatics. The ordinary enablers—those who obey without question—sustain the system as surely as the architects. This polemic endures, with debates persisting over whether Arendt undervalued antisemitism’s visceral role, but her thesis has proven resilient, outlasting the initial fury.

Philosophical Stakes: Redefining Moral Agency

Arendt’s innovation lies in relocating moral responsibility from sentiment to cognition. Agency begins not with feeling but with thought: the deliberate act of judging actions against universal principles. This aligns her work with deeper epistemic concerns, where unexamined beliefs pave the way for ethical collapse. Without the courage to probe “Is this true? Is this right?”, reasoning devolves into rote compliance. The banality of evil thus warns of disengagement in any apparatus—state, corporation, or ideology—where “just following orders” masks profound harm. In an age of institutional sprawl, her call to vigilant judgment remains a bulwark against the mindless perpetuation of injustice.

Lessons for Our Fractured Age: Thoughtlessness in Ideological Currents

Arendt’s framework offers stark lessons amid the ascendance of critical social constructivism, woke Marxism, and gender ideology—movements that, in their zealous conformity, risk replicating the very thoughtlessness she decried. Critical social constructivism, with its insistence that reality bends to narrative power, echoes Eichmann’s euphemistic detachment: truths are “constructed” not discovered, fostering a relativism where evidence yields to doctrinal fiat. Proponents, often ensconced in academic silos, propagate this without interrogating its epistemic costs, much as Arendt saw totalitarianism erode pluralistic inquiry. The result? A moral landscape where dissent is pathologized as “harm,” inverting Socratic dialogue into inquisitorial purity tests.

Woke Marxism, blending identity politics with class warfare rhetoric, amplifies this banality through performative allegiance. What begins as equity advocacy devolves into bureaucratic rituals—DEI mandates, cancel campaigns—that demand uncritical adherence, sidelining the reflective judgment Arendt deemed essential. Critics from leftist traditions note how this mirrors the “administrative massacres” she analyzed, where ideological slogans supplant ethical scrutiny, enabling everyday cruelties under the guise of progress. Ordinary adherents, like Eichmann’s clerks, comply not from malice but from careerist inertia, blind to the dehumanization they abet.

Gender ideology presents perhaps the most poignant parallel, transforming biological verities into fluid “affirmations” via sanitized language that obscures irreversible interventions. Global market projections for sex reassignment surgeries, valued at $3.13 billion in 2025, anticipate reaching $5.21 billion by 2030, underscoring this commodified banality: procedures framed as “care” evade the long-term harms to minors, much as Nazi logistics masked extermination. Voices like J.K. Rowling invoke Arendt directly, highlighting how euphemisms prevent equating these acts with “normal” knowledge of human development. Shallow conformity here—fueled by fear of ostracism—propagates misogynistic erosions of women’s spaces and youth safeguards, all without the depth to confront consequences.

Arendt’s antidote is uncompromising: reclaim thinking as moral praxis. In our screen-lit caves, where algorithms curate consensus and ideologies brook no doubt, we must cultivate epistemic humility—the willingness to question, to pluralize, to judge anew. Only thus can we arrest banality’s creep, ensuring that goodness, radical in its depth, prevails over evil’s empty routine. Thoughtlessness is not fate; it is choice. And in choosing reflection, we honor the dead by fortifying the living against their shadows.

References

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (For concepts of natality and action.)

Berkowitz, R. (2013). “The Banality of Hannah Arendt.” The New York Review of Books, June 6. (On ongoing debates of her thesis.)

Mordor Intelligence. (2024). Sex Reassignment Surgery Market Size, Trends, Outlook 2025–2030. Retrieved October 5, 2025, from https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/sex-reassignment-surgery-market.

Rowling, J. K. [@jk_rowling]. (2024, December 28). “This astounding paper reminds me of Hannah Arendt’s The Banality of Evil…” [Post]. X. https://x.com/jk_rowling/status/1873048335193653387.

Scholem, G. (1964). “Reflections on Eichmann: The Trial of the Historian.” Encounter, 23(3), 25–31. (Open letter critiquing Arendt’s portrayal.)

Villa, D. (1996). Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (For connections to Socratic thinking and totalitarianism.)

Amy Hamm, a British Columbia nurse, faces a $93,811 fine from the B.C. College of Nurses and Midwives (BCCNM) for a thought-crime: stating that humans are biologically sexed and gender identity cannot override this reality. Her off-duty remarks defending women’s sex-based rights, like female-only spaces, were ruled “discriminatory and derogatory” by a disciplinary panel. The decision, released March 13, 2025, followed over 20 days of hearings triggered by activist complaints—not patients—over her support for J.K. Rowling and posts declaring “there are only two sexes.”

Hamm’s ordeal mirrors a Maoist-style struggle session, a public shaming meant to crush dissent. The BCCNM’s 115-page ruling, backed by ideologically aligned “experts,” condemned her for challenging gender identity dogma, equating her advocacy with “erasing” trans existence. No evidence of patient harm surfaced. Yet Hamm—fired without severance by Vancouver Coastal Health—faced harassment, death threats, and accusations of professional misconduct for her views.

This is no anomaly but a trend: regulators weaponize “professional standards” to silence dissent on gender ideology, as seen in the Ontario College of Psychologists’ pursuit of Jordan Peterson for his social media critiques of progressive orthodoxy. Canada’s Charter protects free expression, but bodies like the BCCNM act as enforcers of dogma. Hamm’s appeal to the B.C. Supreme Court, backed by the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, challenges this overreach, but the precedent endangers all who prioritize truth.

Canada’s buckling healthcare system squanders resources on ideological witch hunts while patients languish. Hamm’s near-$100,000 fine for speaking truth signals a nation veering from reason into authoritarian zeal, where dissent becomes heresy and free inquiry burns.

Sources Referenced

- B.C. College of Nurses and Midwives, Discipline Committee Decision, March 13, 2025

- Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, Press Releases, March–April 2025

- National Post, Opinion, April 6, 2025

- Aggregated X posts, August 2025

Canada’s policing landscape reveals a troubling inconsistency, a corrosive double standard that erodes public trust: assaults on Jewish citizens often draw sluggish responses, while those on Muslims prompt swift condemnation and action. Consider the Montreal debacle—a Jewish father beaten in Dickie Moore Park before his terrified children, his kippah tossed into a splash pad like discarded refuse. Police took nearly an hour to arrive, allowing the assailant to vanish, and only arrested him days later amid public furor spurred by community outcry on social media.

Contrast this with Ottawa’s swift response to an unprovoked attack on a young Muslim woman aboard public transit, punched and bombarded with Islamophobic slurs as passengers watched in stunned silence. Authorities immediately labeled it hate-motivated and launched an investigation, reflecting a government commitment to combatting hate crimes. No delay, no limbo—just urgency, as if the system awakens only for select victims.

This disparity is not aberration but pattern. Statistics Canada reports Jews—under 1% of the population—endured over 900 hate crimes in 2023, roughly 70% of religion-based incidents, while Muslim-targeted crimes, numbering around 200, saw faster police action. Yet responses to antisemitic violence often lag, fostering a climate where aggressors act with impunity. Muslims face brutal attacks too, but policing pivots faster, bolstered by vocal leadership. Both communities deserve equal protection; only one consistently receives it.

The irony stings in a nation priding itself on equity: one community’s cries echo unanswered, another’s summon swift shields. Such two-tiered enforcement is not oversight—it is antithetical to justice. If Canada fails to apply equal urgency to all victims, it risks fracturing society into a hierarchy of suffering, dividing rather than uniting against bigotry’s tide.

Sources Referenced

- Statistics Canada, 2023 Hate Crime Report

- CTV News, Montreal, July 2023: Dickie Moore Park assault coverage

- CBC News, Ottawa, June 2023: Transit attack reports

- X posts aggregated from community reports, July 2023

Your opinions…