You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Religion’ category.

This week’s “book I want to read (but haven’t yet)” is Raymond Ibrahim’s Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West. The book is pitched as a long, battle-driven military history: landmark encounters, vivid narration, and a claim that these wars illuminate modern hostilities. It’s explicitly framed as “Islam vs. the West” as a historical through-line, and it advertises heavy use of primary sources (notably Arabic and Greek) to tell that story. (Barnes & Noble)

The thesis, as Ibrahim presents it in descriptions and interviews, is that the conflict is not merely politics or economics—it’s substantially religious and civilizational in motive and self-understanding across centuries. In short: jihad (as an animating concept) and sacred duty are treated as durable drivers; key episodes are used to argue continuity rather than accident. Even the “origin story” in some blurbs is framed in explicitly religious terms (conversion demand → refusal → centuries-long jihad on Christendom), which signals the interpretive lens: ideas and theology matter, and they matter a lot. (Better World Books)

Why I’m flagging it for the DWR Sunday Religious Disservice: it’s a strong claim, not a neutral survey—and it’s the kind of claim you should read with a second book open beside it. Supportive reviews praise it as a bracing corrective to “sanitized” histories; skeptical academic commentary warns that it can function as an intervention that frames Islam first and foremost through antagonism and “civilizational conflict,” which can flatten variation across time, place, and Muslim societies. So the honest pitch is: this is Ibrahim’s argument; it may sharpen your sight—or narrow it—depending on what you pair it with. (catholicworldreport.com)

Endnotes

- Publisher/retailer description (scope + primary sources framing): (Barnes & Noble)

- “Origin story” / jihad framing in overview copy: (Better World Books)

- Interview-style framing of “landmark battles” thesis: (Middle East Forum)

- Critical scholarly pushback (civilizational conflict lens): (Reddit)

The West keeps making a category error. It treats Islam as “a religion” in the narrow civic sense modern liberal societies usually mean: private belief, voluntary worship, and a clean separation between pulpit and state.

Islam can be lived that way. Many Muslims do live that way. But Islam, as a tradition, also carries a developed legal–political vocabulary: a picture of how authority, law, community, and public order ought to be arranged. That does not make Muslims suspect. It makes Western assumptions incomplete. A liberal society can only defend what it can name.

A faith that has historically included law

In the classical Islamic tradition, sharia is not only “spiritual guidance.” It is commonly described as governing interpersonal conduct and regulating ritual practice, and in some countries it is applied as governing law or in specific legal domains. (Judiciaries Worldwide) That matters because the modern West is built on a particular settlement: religious freedom inside a civic order that does not belong to any religion.

The relationship between religion and governance in Islamic history also does not map neatly onto the European story of Church versus state. Even critics of the simplistic slogan that Islam “fuses religion and politics” concede a real point beneath it: Muslim thinkers draw distinctions between din (religion) and dawla (state), but the domains and their interrelations do not mirror the European pattern. (MERIP)

So when Western elites insist, “Islam is just a religion,” they are not being tolerant. They are being imprecise. And imprecision is how liberal societies lose arguments before they begin.

The distinction that matters: Islam and Islamism

Precision starts by separating two things that get blurred, sometimes by ignorance, sometimes by strategy:

- Islam: a religion with immense internal diversity, spiritual, legal, philosophical, cultural.

- Islamism (political Islam): a broad set of political ideologies that draw on Islamic symbols and traditions in pursuit of sociopolitical objectives. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A devout Muslim can reject Islamism. A culturally Muslim person can reject Islamism. A believer can treat sharia as personal ethics while rejecting its coercive imposition in a pluralist state. Islamic sources themselves contain the frequently cited line: “Let there be no compulsion in religion.” (Quran.com)

But it is also true that in many parts of the world, substantial numbers of Muslims express support for making sharia “the official law of the land.” (Pew Research Center) That doesn’t prove anything about your Muslim neighbour in Edmonton. It does establish something narrower and important: the political question is not imaginary. It is not a fringe invention.

The engine: infallible doctrine, universal horizon

The political question is whether a movement treats its doctrine as a governing blueprint, one that must eventually become public authority. That is what makes Islamism different from ordinary piety: it is not satisfied with private devotion or voluntary community. It wants law, policy, and state power aligned to a sacred ideal.

If you want a useful analogue for how Islamism works, look at Marxism. Not in theology, mechanics. The doctrine is treated as infallible, so failure can’t belong to the doctrine; it must belong to the people, the impurities, or the enemies. That logic produces a predictable politics: dissent becomes not an alternative view but a problem to be managed, re-educated, or removed.

From there, the “universal” impulse makes sense. This is not always military conquest talk. More often it is a civilizational horizon: the expectation that Islam should be socially and politically ascendant, with public authority aligned to that vision. Classical Islamic political vocabulary has long included categories describing the realm where Islam has “ascendance,” historically paired with an external realm. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A liberal society can coexist with any faith. It cannot coexist with a program that treats liberal pluralism as a temporary obstacle to be overcome.

What the West keeps getting wrong

Western discourse often collapses three claims into one muddy accusation:

- “Muslims are dangerous.” False, unfair, and morally corrosive.

- “Islam has a legal–political tradition.” True, and visible in texts, history, and institutions. (Judiciaries Worldwide)

- “Islamism is a modern political project that can conflict with liberal norms.” True, and increasingly relevant. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

If claims (2) and (3) are denied out of fear of sounding like (1), the result is not compassion. It is blindness. And blindness is not a strategy.

What a liberal society should do

This does not require panic. It requires clarity.

First, speak precisely. Say “Islamism” when you mean political ideology. Say “Islam” when you mean the religion broadly. Don’t use a sweeping civilizational label to do the work of a specific critique.

Second, draw the civic line cleanly: the liberal state is not negotiable. Freedom of worship is protected. Violence and harassment are punished. Attempts to import coercive religious governance into public law are rejected.

Third, stop outsourcing integration to slogans. Liberalism is not a magic solvent. It is a culture of habits, rights, obligations, and red lines that must be taught and applied evenly.

Fourth, refuse collective guilt. Defend liberal norms without treating ordinary Muslims as a fifth column. A society can oppose an illiberal political project while still welcoming neighbours who want to live in peace.

Here is the honesty sentence: if political Islam is largely marginal in Western societies, with negligible institutional influence and no meaningful appetite for parallel authority, the urgency of this argument drops. If, instead, organized efforts continue to carve out exemptions from liberal norms, to pressure institutions into censorship, or to substitute religious authority for civic law, the urgency rises.

The West doesn’t need a religious war. It needs vocabulary. It needs the courage to name ideological ambition without demonizing human beings. And it needs to remember that liberalism is not the default state of humanity. It is a fragile achievement that survives only when people are willing to defend it

References

- Federal Judicial Center, “Islamic Law and Legal Systems” (overview of sharia as governing interpersonal conduct/ritual practice; sometimes governing law). (Judiciaries Worldwide)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Islamism” (definition as political ideologies pursuing sociopolitical objectives using Islamic symbols/traditions). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Pew Research Center, The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society (overview and chapter on beliefs about sharia; questionnaire language on making sharia official law). (Pew Research Center)

- MERIP, “What is Political Islam?” (discussion of din/dawla and why European categories don’t map neatly). (MERIP)

- MERIP, “Islamist Notions of Democracy” (notes the common modern formulation of “religion and state” and its relationship to secularism debates). (MERIP)

- Qur’an 2:256 (“no compulsion in religion”) and Ibn Kathir tafsir page commonly cited in discussion. (Quran.com)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Dār al-Islām” (political-ideological category describing the realm where Islam has ascendance, traditionally paired with an external realm). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Screenshot

If you missed what I’m talking about please look at the post from this Sunday’s The DWR Sunday Religious Disservice – Why Classical Islam and Western Liberalism Face Deep Tensions.

1) “You’re Confusing Islam with Islamism. The Problem Is Politics, Not the Religion.”

Steelman: Islamism is a modern political project. The ugly stuff is authoritarianism in religious costume. Islam as faith is diverse and reformable. Reformers exist. So don’t blame the religion for the politics.

My answer: The distinction is real. It just doesn’t rescue the claim.

Modern Islamism didn’t invent the collision with liberalism. It accelerated it. The collision is older, because it sits inside a legal tradition that treats divine law as public law, not private devotion.

Start with the liberal baseline: your right to change your beliefs without state punishment. The ICCPR treats freedom of thought, conscience, and religion as including the freedom “to have or to adopt” a religion of one’s choice, and bars coercion that impairs that freedom.[1] Yet apostasy laws still exist as state law in a chunk of the world. Pew counted apostasy laws in 22 countries in 2019.[2] That’s not “Islamism only.” That’s a standing fact about legal systems and what they’re willing to criminalize.

Then there are the asymmetries that aren’t modern inventions at all. The Qur’an’s inheritance rule that the male share is “twice that of the female” is explicit.[3] So is the debt-contract witness standard that requires one man and two women in that context.[4] You can contextualize these. You can argue for limited scope. You can try to reinterpret. But you can’t pretend the hard edges arrived in the 20th century.

So yes: reform is possible. But the obstacle is not merely “bad regimes.” It’s the weight of inherited jurisprudence plus institutions that treat that inheritance as binding.

If you want a clean test, use this: Is conscience sovereign? Including the right to leave the faith without legal penalty. Where the answer is no, liberalism exists on permission, not principle.

2) “Western Civilization Has Its Own History of Religious Violence and Oppression.”

Steelman: Christianity did crusades, inquisitions, heresy executions, and legal oppression. Liberalism took centuries. So singling out Islam is selective and hypocritical. Islam may simply be earlier in the same process.

My answer: Fair comparison. Now use it properly.

The West didn’t become liberal because Christians became nicer. It became liberal because religious authority was structurally pushed out of sovereignty over law and conscience. That’s the real lesson.

If “Islam can modernize” is your claim, then define modernization. It means a public order in which equal citizenship is non-negotiable and the right to belief and exit is protected in law.[1] You don’t get there by vibes. You get there by institutions.

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution is a useful example precisely because it shows the tension in plain language. It says the state is “guardian of religion,” while also guaranteeing “freedom of conscience and belief.”[5] That’s the struggle in one paragraph: which sovereignty rules when the two conflict?

Morocco’s family-law reforms are another example of the same dynamic. Over time, reforms have expanded women’s rights in areas like guardianship and divorce.[6] But even current reform proposals acknowledge a hard limit: inheritance rules grounded in Islamic law remain, with workarounds proposed through gifts and wills rather than direct replacement.[7] Again, that’s not a moral condemnation. It’s the mechanism. Reform runs into inherited authority.

So yes: the Western analogy shows change is possible. It also shows change is not automatic. It is conflict, choices, and enforcement.

3) “You’re Ignoring Diversity in the Muslim World and Overgeneralizing.”

Steelman: Nearly two billion adherents across many cultures and legal systems. Outcomes vary widely. Some Muslim-majority societies are relatively pluralistic. Sweeping statements are unfair.

My answer: Diversity is real. It just doesn’t settle the core question.

Different outcomes prove the future isn’t predetermined. They don’t prove the underlying tension disappears. In practice, “moderation” usually correlates with one thing: how far the state limits religious jurisdiction over public law.

Indonesia is the standard example. Its founding philosophy, Pancasila, is explicitly framed as a unifying civic ideology with principles including belief in one God, deliberative democracy, and social justice.[8] That civic framing matters. It can restrain sectarian rule. But it doesn’t end the conflict.

Indonesia’s newer criminal code debates show how quickly “public morality” and “religious insult” can become tools against liberty. Reuters’ explainer on the code flagged concerns over provisions related to blasphemy and other speech constraints.[9] Human Rights Watch argued the updated code expanded blasphemy provisions and warned about harms to rights, including religious freedom.[10] Reuters has also reported concrete blasphemy prosecutions, including a comedian jailed for jokes about the name Muhammad.[11]

So yes: diversity exists. Outcomes differ. But the recurring fault line remains: whether the state treats conscience and equal citizenship as the top rule, or treats religious law as a superior jurisdiction that liberalism must negotiate with.

Closing

The best objections don’t erase the problem. They refine it.

The conflict is not “Muslims are bad.” That’s a cheap and stupid sentence. The conflict is structural: a comprehensive religious-legal tradition claiming public authority collides with a political order grounded in sovereignty of individual conscience.[1]

You don’t solve that conflict by saying “it’s just politics.” You don’t solve it by reciting Western sins as a deflection. You don’t solve it by pointing to diversity and declaring victory.

A liberal society survives by enforcing liberal public order: one civil law for all, equal rights as the baseline, and no religious veto over belief, speech, or exit.[1] If you refuse to name that clearly, you don’t get “coexistence.” You get drift. And drift always has a direction.

References (URLs)

[1] OHCHR — International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 18

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

[2] Pew Research Center — Four in ten countries… had blasphemy laws in 2019 (includes apostasy law count) (Jan 25, 2022)

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/25/four-in-ten-countries-and-territories-worldwide-had-blasphemy-laws-in-2019-2/

[3] Qur’an 4:11 (inheritance shares) — Quran.com

https://quran.com/en/an-nisa/11-14

[4] Qur’an 2:282 (witness standard in debt contracts) — Quran.com

https://quran.com/en/al-baqarah/282

[5] Tunisia 2014 Constitution, Article 6 — Constitute Project

https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014

[6] Carnegie Endowment — Morocco Family Law (Moudawana) Reform: Governance in the Kingdom (Jul 28, 2025)

https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/07/morocco-family-law-moudawana-reform-governance?lang=en

[7] Reuters — Morocco proposes family law reforms to improve women’s rights (Dec 24, 2024)

https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/morocco-proposes-family-law-reforms-improve-womens-rights-2024-12-24/

[8] Encyclopaedia Britannica — Pancasila

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pancasila

[9] Reuters — Explainer: Why is Indonesia’s new criminal code so controversial? (Dec 6, 2022)

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-is-indonesias-new-criminal-code-so-controversial-2022-12-06/

[10] Human Rights Watch — Indonesia: New Criminal Code Disastrous for Rights (Dec 8, 2022)

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/08/indonesia-new-criminal-code-disastrous-rights

[11] Reuters — Indonesian court jails comedian for joking about the name Muhammad (Jun 11, 2024)

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesian-court-jails-comedian-joking-about-name-muhammad-2024-06-11/

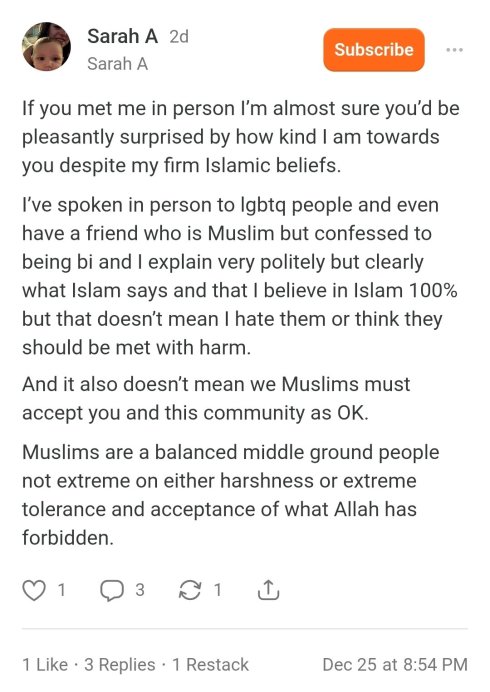

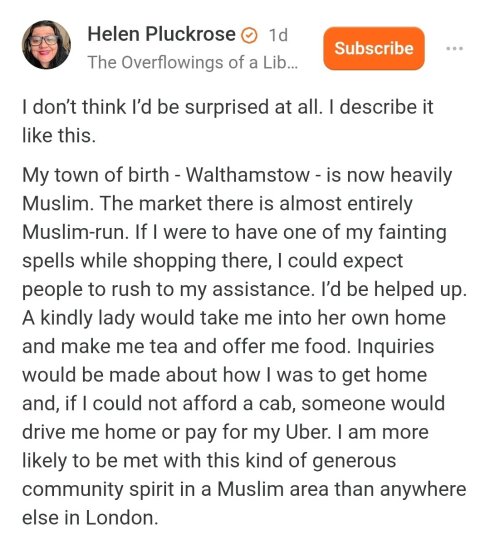

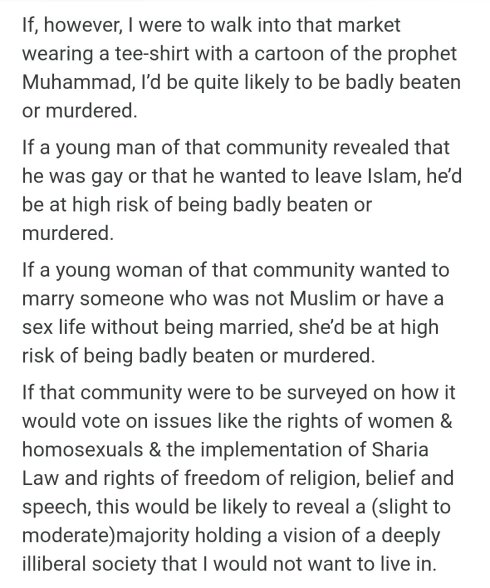

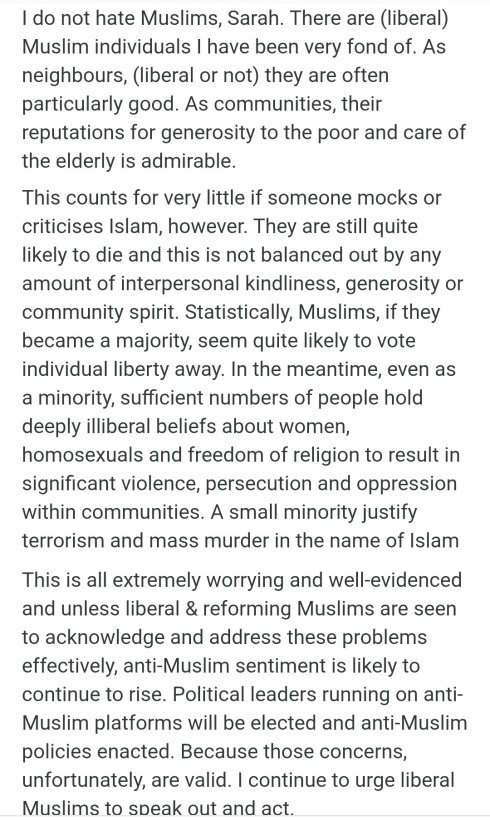

In a thoughtful exchange highlighted by James Lindsay, liberal writer Helen Pluckrose responds to a Muslim commenter who shares personal experiences of generosity within Muslim communities. While warmly acknowledging the kindness and charity she’s witnessed among individual Muslims, Pluckrose firmly points out the broader issue: widespread support in some Muslim populations for Sharia-based views that endorse severe punishments—including violence or death—for apostasy, homosexuality, adultery, and blasphemy. She argues that ignoring these illiberal attitudes, backed by polling data, risks fueling unnecessary backlash against Muslims while failing to address genuine incompatibilities with Western liberal values.

Your opinions…