Screenshot

Canadian cogitations about politics, social issues, and science. Vituperation optional.

Screenshot

The Age of Discovery was not a morality play. It was a capability leap. Between the late 1400s and the 1600s, Europeans built a durable system of oceanic navigation, mapping, and logistics that connected continents at scale. That system reshaped trade, ecology, science, and eventually politics across the world.

None of this requires sanitizing what came with it. Disease shocks, conquest, extraction, and slavery were not side notes. They were part of the story. The problem is what happens when modern retellings keep only one side of the ledger. When “discovery” is taught as a synonym for “oppression,” history stops being inquiry and becomes a single moral script.

The Age of Discovery solved practical problems that had limited long-range sea travel: how to travel farther from coasts, how to fix position reliably, and how to represent the world in a form that could be used again by the next crew.

Routes mattered first. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and helped establish the sea-route logic that linked the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean world. That made long voyages less like stunts and more like repeatable corridors.

Maps made it scalable. In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller’s map labeled “America” and presented the newly charted lands as a distinct hemisphere in European cartography. In 1569, Mercator’s projection made course-setting more practical by letting navigators plot constant bearings as straight lines. These were not aesthetic achievements. They were infrastructure for a global system.

Instruments and technique followed. Mariners relied on celestial measurement, and Europeans benefited from earlier work in the Islamic world and medieval transmission routes that carried astronomical knowledge and instrument development into Europe. This is worth stating plainly because it strengthens the real point: the Age of Discovery was not magic. It was the synthesis and scaling of knowledge into a logistical machine.

Finally, there was proof of global integration. Magellan’s expedition, completed after his death by Juan Sebastián del Cano, achieved the first circumnavigation. Whatever moral judgments one makes about the broader era, this was a genuine expansion of what humans could do and know.

The same system that connected worlds also carried catastrophe.

Indigenous depopulation after 1492 was enormous. Scholars debate the causal mix across regions, but the scale is not seriously in dispute. One influential synthesis reports a fall from just over 50 million in 1492 to just over 5 million by 1650, with Eurasian diseases playing a central role alongside violence, displacement, and social disruption.

The transatlantic slave trade likewise expanded into a vast engine of forced migration and brutal labor. Best estimates place roughly 12.5 million people embarked, with about 10.7 million surviving the Middle Passage and arriving in the Americas. These are not “complications.” They are central moral facts.

And the Columbian Exchange, often simplified into “new foods,” was a sweeping biological and cultural transfer that included crops and animals, but also pathogens and ecological disruption. It permanently altered diets, landscapes, and power.

A reader can acknowledge all of that and still resist a common conclusion: that the entire era should be treated as a civilizational stain rather than a mixed human episode with world-changing outputs.

A fact-based account has to hold two truths at once.

First, the biological transfer had large, measurable benefits. Economic historians have argued that a single crop, the potato, can plausibly explain about one-quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900. That is a civilizational consequence, not an opinion.

Second, the same transoceanic link that moved calories also moved coercion and disease. That is not a footnote. It is part of the mechanism.

The adult position is not denial and not self-flagellation. It is proportionality.

Critical theory is not one thing. In the broad sense, it names a family of approaches aimed at critique and transformation of society, often by making power, incentives, and hidden assumptions visible. In that role, it can correct older triumphalist histories that ignored victims and treated conquest as background noise.

The failure mode appears when the lens becomes total. When domination becomes the only explanatory variable, achievement becomes suspect simply because it is achievement, and complexity is treated as apology. The story turns into prosecution.

One can see the tension in popular history writing. Howard Zinn’s project, for example, explicitly recasts familiar episodes through the eyes of the conquered and the marginalized. That corrective impulse can be valuable. But critics such as Sam Wineburg have argued that the method often trades multi-causal history for moral certainty, producing a “single right answer” style of interpretation rather than a discipline of competing explanations. The risk is that students learn a posture instead of learning judgment.

A parallel point is worth making for Indigenous-centered accounts. Works like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s are explicit that “discovery” is often better described as invasion and settler expansion. Even when one disagrees with some emphases, the existence of that challenge is healthy. It forces the older story to grow up.

But there is a difference between correction and replacement. Corrective history adds missing facts and voices. Replacement history insists there is only one permissible meaning.

Western civilization does not need to be imagined as flawless to be defended as consequential and often beneficial. The Age of Discovery expanded human capabilities in navigation, cartography, and global integration. It also produced immense suffering through disease collapse, coercion, and slavery.

A healthy civic memory holds both sides of that ledger. It teaches the costs without denying the achievements, and it refuses any ideology that demands a single moral story as the price of belonging.

Bartolomeu Dias (1488) — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bartolomeu-Dias

Recognizing and Naming America (Waldseemüller 1507) — Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/collections/discovery-and-exploration/articles-and-essays/recognizing-and-naming-america/

Mercator projection — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/science/Mercator-projection

Magellan and the first circumnavigation; del Cano — Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-Magellan

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Sebastian-del-Cano

Mariner’s astrolabe and transmission via al-Andalus — Mariners’ Museum

European mariners owed much to Arab astronomers — U.S. Naval Institute (Proceedings)

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1992/december/navigators-1490s

Indian Ocean trade routes as a pre-existing global network — OER Project

https://www.oerproject.com/OER-Materials/OER-Media/HTML-Articles/Origins/Unit5/Indian-Ocean-Routes

Indigenous demographic collapse (1492–1650) — British Academy (Newson)

Transatlantic slave trade estimates — SlaveVoyages overview; NEH database project

https://legacy.slavevoyages.org/blog/brief-overview-trans-atlantic-slave-trade

https://www.neh.gov/project/transatlantic-slave-trade-database

Potato and Old World population/urbanization growth — Nunn & Qian (QJE paper/PDF)

Click to access NunnQian2011.pdf

Critical theory (as a family of theories; Frankfurt School in the narrow sense) — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/

Zinn critique: “Undue Certainty” — Sam Wineburg, American Educator (PDF)

https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2012-2013

Indigenous-centered framing (as a counter-story) — Beacon Press (Dunbar-Ortiz)

https://www.beacon.org/An-Indigenous-Peoples-History-of-the-United-States-P1164.aspx

“Trump Derangement Syndrome” (TDS) isn’t a medical condition. It’s a rhetorical label for a recognizable pattern: Donald Trump becomes the organizing centre of political perception, so that every event is interpreted through him, and every interpretation is pulled toward maximal moral heat. Even people who agree on the facts can’t agree on the temperature, because the temperature is the point. Psychology writers describe it as a derogatory term for toxic, disproportionate reactions to Trump’s statements and actions.

And when politicians try to literalize it as a clinical diagnosis, it collapses into farce. It is fundamentally a political phenomenon, not a psychiatric one.

The useful question isn’t “Is Trump uniquely bad?” Reasonable people can say yes on qualities character, norms, rhetoric, policy, whatever. The useful question is: when does valid criticism become TDS? The answer is: when Trump stops being an object of analysis and becomes a gravity well.

Normal criticism is specific: this policy, this consequence, this evidence, this alternative. TDS is different in kind.

Totalization: Trump isn’t a president with a platform; he’s a single-cause explanation for everything.

Asymmetry: Similar behaviour in other leaders is background noise; in Trump it becomes existential threat (or, on the other side, heroic 4D chess).

Incentive blindness: The critic’s emotional reward (“I signaled correctly”) overrides the duty to be precise.

Predictable misreads: Even when Trump does something ordinary or mixed, it must be either apocalypse or genius.

This is why the term persists. It points generallyat a real cognitive trap: a personality-driven politics that makes judgment brittle. (It also gets used cynically to dismiss legitimate criticism; that’s part of the ecosystem, too.)

Canada didn’t invent Trump fixation. But Canadian legacy media has strong reasons to keep Trump on the homepage. The reasons, in question, are not purely ideological.

1) Material proximity (it’s not “foreign news” in Canada).

When the U.S. president threatens tariffs, trade reprisals, or bilateral negotiations, Canadians feel it directly: jobs, prices, investment, and national policy all move. In Trump’s second term, Canadian economic and political life has repeatedly been forced to react to U.S. pressure: tariffs, trade disputes, and negotiations that shape Ottawa’s choices.

That creates a built-in news logic: Trump coverage is “domestic-adjacent,” not optional.

2) An attention model that rewards moral theatre.

Trump is an outrage engine. Outrage is a business model. Canadian mediais operating in a trust-and-revenue squeeze, and that squeeze selects for stories that reliably produce engagement. Commentators on Canada’s media crisis have argued that the Trump era intensified the trust spiral and the incentives toward heightened, adversarial framing.

3) Narrative convenience: Trump as a single, portable explanation.

Complex stories (housing, health systems, provincial-federal dysfunction) are hard. Trump is easy: one villain (or saviour), one emotional script, one endless drip of “breaking.” This is where amplification turns into distortion. A real cross-border policy dispute becomes a morality play; a complicated negotiation becomes a personality drama.

4) Coverage volume becomes self-justifying.

Once a newsroom commits, it has to keep feeding the lane it created. Tools that track Canadian legacy-media coverage of Trump-related economic conflict like tariffs for example, show how sustained and multi-outlet that attention can become.

The more space Trump occupies, the more “newsworthy” he becomes, because “everyone is talking about it” (including the newsroom).

None of this requires a conspiracy. It’s mostly incentive alignment: relevance + engagement + a simple narrative hook.

The predictable result is that Canadians import not just U.S. events, but U.S. emotional calibration.

Canadian politics gets interpreted as a shadow-play of American factions.

Domestic accountability weakens (“our problems are downstream of Trump / anti-Trump”).

Readers get trained to react first and think second, a reinforcing heuristic, because that’s what the coverage rewards.

And it corrodes trust: if audiences can feel when coverage is performing emotional certainty rather than reporting reality, they stop believing the institution is trying to be fair.

If this is going to be useful (not tribal), it needs a diagnostic you can run on yourself and on coverage:

Specificity test: Is the criticism about a policy and its consequences, or about Trump as a symbol?

Symmetry test: Would you report/feel the same way if a different president did it?

Proportionality test: Does the language match the evidence, or does it leap straight to existential claims?

Update test: When new facts arrive, does the story change—or does the narrative stay fixed?

Trade-off test: Are costs and alternatives discussed, or is “opposition” treated as sufficient analysis?

Pass those tests and you’re probably doing real criticism. Fail them repeatedly and you’re in the gravity well regardless of whether the content is rage or adoration.

Trump is a legitimate target for strong criticism especially in a second term with direct consequences for Canada.

But the deeper media failure is not “being anti-Trump.” It’s outsourcing judgment to a narrative reflex: a system that selects for maximal heat, maximal frequency, and minimal precision. That’s how valid critique curdles into derangement—because it stops being about what happened, and becomes about what the story needs.

The fix is boring, which is why it’s rare: lower the temperature, raise the specificity, and let facts earn the conclusion.

Psychology Today — “The Paradox of ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’” (Sep 5, 2024)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-meaningful-life/202409/the-paradox-of-trump-derangement-syndrome

The Loop (ECPR) — “Is ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’ a genuine mental illness?” (Oct 13, 2025)

CBS News Minnesota — “Minnesota Senate Republicans’ bill to define ‘Trump derangement syndrome’ as mental illness…” (Mar 17, 2025)

https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/trump-derangement-syndrome-minnesota-senate-republicans/

Reuters Institute — Digital News Report 2025: Canada (Jun 17, 2025)

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2025/canada

The Trust Spiral (Tara Henley) — The state of media/trust dynamics (May 2024)

Reuters — “Trump puts 35% tariff on Canada…” (Jul 11, 2025)

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-puts-35-tariff-canada-eyes-15-20-tariffs-others-2025-07-11/

Financial Times — “Canada scraps tech tax to advance trade talks with Donald Trump” (Jun 30, 2025)

https://www.ft.com/content/4cf98ada-7164-415d-95df-43609384a0e2

The Guardian — “White House says Canadian PM ‘caved’ to Trump demand to scrap tech tax” (Jun 30, 2025)

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/30/canada-digital-services-tax-technology-giants-us-trade-talks

The Plakhov Group — Trade War: interactive visualizations of Canadian legacy-media coverage of Trump’s tariffs (Feb–Sep 2025 dataset)

https://www.theplakhovgroup.ca/detailed-briefs/trade-war-interactive-visualizations

When Iran’s streets erupt, the regime’s first move is rarely ideological persuasion. It is logistical suffocation: arrests, fear, and the severing of communication. In early January 2026, reporting described widespread internet and phone disruptions as protests intensified. The point is not subtle. A state that can’t control bodies tries to control visibility.

Western audiences, meanwhile, do not experience Iran directly. They experience coverage: what makes the front page, what becomes “live,” what gets a correspondent, what earns context, what gets a single write-up and then disappears. That gatekeeping function doesn’t require fabrication to shape reality. It only requires allocation. In practice, editorial choices determine whether an uprising feels like history in motion or distant static.

The claim here is narrower than the familiar “the media lies” complaint. It is this: large news institutions can augment or diminish a story by controlling three dials — timing, framing, and follow-through — and those dials often track narrative comfort as much as factual urgency.

Iran’s protest cycle began in late December 2025 and accelerated quickly. Wire reporting described large demonstrations after the rial hit record lows, police using tear gas, and protests spreading beyond Tehran. A few days later, reporting increasingly emphasized the state’s repression and the communications clampdown as the crisis deepened. By January 8–10, the blackout itself and the scale of unrest were central features in major coverage, alongside reports of deaths, detentions, and intensifying crackdowns.

None of this is to say “there was no coverage.” There was. The question is what kind of coverage it became, and when. A story can exist in print while being functionally minimized: treated as episodic, framed as local disorder, or kept at a low hum until a single undeniable hook forces it to the foreground. In this cycle, the communications cutoff became that hook — a reportable meta-event that is easy to verify and hard to ignore.

The BBC dispute is illustrative. Public criticism accused the BBC of thin or late attention; BBC News PR rebutted that claim. The argument itself is the point: audiences can feel the throttle even when they cannot quantify it precisely. When trust collapses, people start timing the coverage.

1) Timing: when an event is treated as real.

In closed societies, early information is messy: shaky videos, activist claims, regime denials, and silence during blackouts. Caution can be defensible. But caution is also a convenient lever. If the bar for “confirmed” rises selectively, timidity becomes bias with clean hands. The public doesn’t see the internal deliberations; it sees the lag — and a lag signals “this isn’t important.”

2) Framing: what the story is about.

A protest can be framed as “economic unrest,” “public anger,” “unrest,” “crackdown,” or “a legitimacy crisis.” These are not synonyms. Each frame assigns agency and moral clarity differently.

“Economic unrest” implies weather: hardship produces crowds, crowds disperse, life continues. “Legitimacy crisis” implies politics: a governing order is being contested. Amnesty’s language, for example, emphasizes lethal state force; Reuters emphasizes regime warnings and suppression; AP emphasizes spread, detentions, and the hard edge of state response. Those differences matter because they tell the audience whether this is a temporary spasm or a turning point.

3) Follow-through: whether the story becomes a continuing reality.

One report is not coverage. Coverage is cadence: daily updates, on-the-ground reporting, explanatory context, and sustained attention when the situation is still unclear. Regimes understand this. A blackout isn’t only about disrupting domestic coordination; it also disrupts the foreign media rhythm that turns unrest into sustained international pressure.

There are good reasons major outlets hesitate:

verification is genuinely difficult during shutdowns,

misinformation can be weaponized by the regime and opportunists,

reckless amplification can endanger sources.

These are real constraints, not excuses. But they are only persuasive when applied consistently. The public’s frustration arises when “we can’t confirm” functions as a brake on some stories and not others — when caution looks less like discipline and more like selective incredulity.

A useful concept must do more than flatter a tribe. It should help a reader detect when they are being shown an event versus being shown a story about the event. This can be done with a simple diagnostic — the Narrative Throttle Test:

Latency: How long did it take for a major outlet to treat it as major?

Vocabulary drift: Did coverage move from “unrest” to “crisis” only after the evidence became unavoidable?

Cadence: Was it sustained, or did it appear as isolated updates with no continuity?

Agency: Were protesters described as political actors with aims, or as reactive crowds with emotions?

Comparative salience: What else dominated the same window, and why?

These questions do not require assuming malice. They only require accepting that agenda-setting is power — and that power is exercised even by institutions that believe they are merely “reporting.”

Iran’s future will be decided in Iran. But the West’s perception of Iran is decided in newsrooms. When coverage is delayed, flattened, or treated as a passing disturbance, the public receives a smaller event than the one unfolding. That matters because attention is a constraint on brutality. It is not the only constraint, and it is not always sufficient — but it is real.

The cleanest conclusion is also the least dramatic:

Facts do not reach the public raw. Institutions deliver them — loudly, softly, or not at all.

References

AP — Protests erupt in Iran over currency’s plunge to record low (Dec 29, 2025)

https://apnews.com/article/ddc955739fb412b642251dee10638f03

AP — Protests near the 2-week mark as authorities intensify crackdown (Jan 10, 2026)

https://apnews.com/article/c867cd53c99585cc5e0cd98eafe95d16

Reuters — Iran cut off from world as supreme leader warns protesters (Jan 9, 2026)

https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-cut-off-world-supreme-leader-warns-protesters-2026-01-09/

The Guardian — Iran plunged into internet blackout as protests spread (Jan 8, 2026)

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/08/iran-plunged-into-internet-blackout-as-protests-over-economy-spread-nationwide

Amnesty International Canada — Deaths and injuries rise amid renewed cycle of protest bloodshed (Jan 8, 2026)

https://amnesty.ca/human-rights-news/iran-deaths-injuries-renewed-cycle-protest-bloodshed/

BBC report mirrored via AOL — Huge anti-government protests in Tehran and other cities, videos show (Jan 8–9, 2026)

https://www.aol.com/articles/iran-regime-cuts-nationwide-internet-003409430.html

https://ca.news.yahoo.com/large-crowds-protesting-against-iranian-201839496.html

BBC report mirrored via ModernGhana — Iran crisis deepens: protests spread with chants of “death to the dictator” (Dec 31, 2025)

https://www.modernghana.com/videonews/bbc/5/597647/

Telegraph (commentary) — Critique of BBC’s Iran coverage (Jan 9, 2026)

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2026/01/09/the-bbc-iran-coverage-poor/

BBC News PR tweet responding to coverage criticism (Jan 2026)

https://x.com/BBCNewsPR/status/2007048343793570289

CTP-ISW — Iran Update (Jan 5, 2026)

https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-update-january-5-2026

CTP-ISW — Iran Update (Jan 9, 2026)

https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-update-january-9-2026

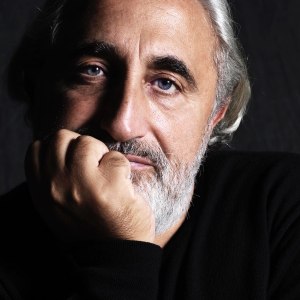

Suicidal empathy is a term Dr. Gad Saad uses to describe a specific failure mode of compassion: empathy that gets detached from boundaries, reciprocity, and cost-accounting—until it starts producing outcomes that harm the very people and institutions doing the empathizing.

Read it less as a diagnosis and more as a warning label. Empathy is normally a pro-social tool. It helps humans cooperate, care for dependents, and build trust. But like any tool, it can be misapplied. When empathy becomes an unconditional rule (“the compassionate option must always win”), it stops asking the questions that keep compassion functional: Who pays? Who benefits? What incentives are we creating? What happens if this scales?

That’s the central mechanism. Unbounded empathy deactivates trade-offs. It treats limits as moral failure, and it treats enforcement as cruelty. In public life, that often looks like policies designed around the needs of the claimant while steadily eroding the duties owed to the steward—the taxpayer, the law-abiding neighbor, the already-vulnerable person living downstream of disorder. It isn’t that compassion is wrong; it’s that compassion without accounting becomes a transfer of risk onto the conscientious.

If you want this concept to be useful—rather than partisan—you need a clean heuristic. Here’s one:

When you see a “compassion-first” policy, norm, or movement, ask:

Where does the cost land?

Is the cost paid by decision-makers, or exported onto people with less voice?

What happens at scale?

Would this still work if adopted widely, or is it only viable as a boutique exception?

What incentives does it create?

Does it reward responsibility and reciprocity—or does it reward manipulation, noncompliance, or repeat harm?

Are boundaries being treated as immoral by definition?

If the only “good” option is the one that refuses limits, you’re not doing ethics—you’re doing sentiment.

Does it erode the conditions that make generosity possible?

High-trust societies can afford softness because they still enforce norms. If the proposal weakens trust, safety, or shared obligation, it may be burning the fuel empathy runs on.

You don’t need cynicism to apply this test. You just need the willingness to treat compassion as something that must be paired with responsibility. The point isn’t to feel less—it’s to see more: the second-order effects, the incentives, the people who silently pay. If empathy can’t survive contact with those questions, it isn’t moral courage. It’s moral vanity with a body count.

References

Suicidal Empathy (publisher page – HarperCollins / Broadside Books)

https://www.harpercollins.com/products/suicidal-empathy-gad-saad

Gad Saad – Concordia University faculty profile

https://www.concordia.ca/faculty/gad-saad.html

The Parasitic Mind (publisher page – Simon & Schuster)

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Parasitic-Mind/Gad-Saad/9781621579939

Gad Saad – Psychology Today contributor page

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/contributors/gad-saad-phd

Suicidal Empathy (Audible Canada listing – includes release date/details)

https://www.audible.ca/pd/Suicidal-Empathy-Audiobook/B0FZ6JMVFQ

Religion. Politics. Life.

Solve ALL the Problems

Art, health, civilizations, photography, nature, books, recipes, etc.

Independent source for the top stories in worldwide gender identity news

LESBIAN SF & FANTASY WRITER, & ADVENTURER

herstory. poetry. recipes. rants.

Communications, politics, peace and justice

Transgender Teacher and Journalist

Conceptual spaces: politics, philosophy, art, literature, religion, cultural history

Loving, Growing, Being

A topnotch WordPress.com site

Life After an Emotionally Abusive Relationship

No product, no face paint. I am enough.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Observations and analysis on survival, love and struggle

the feminist exhibition space at the university of alberta

About gender, identity, parenting and containing multitudes

Spreading the dangerous disease of radical feminism

Not Afraid Of Virginia Woolf

The Evolution Will Not BeTelevised

writer, doctor, wearer of many hats

Teaching Artist/ Progressive Educator

Identifying as female since the dawn of time.

A blog by Helen Saxby

A blog in support of Helen Steel

Where media credibility has been reborn.

Memoirs of a Butch Lesbian

Radical Feminism Discourse

deconstructing identity and culture

Fighting For Female Liberation from Patriarchy

Politics, things that make you think, and recreational breaks

cranky. joyful. radical. funny. feminist.

Movement for the Abolition of Prostitution

These are the best links shared by people working with WordPress

Gender is the Problem, Not the Solution

Peak Trans and other feminist topics

if you don't like the news, make some of your own

Musing over important things. More questions than answers.

short commentaries, pretty pictures and strong opinions

gender-critical sex-negative intersectional radical feminism

Your opinions…